What the Hong Kong protests can teach the world about enduring social movements

Dressed head to toe in the black gear of Hong Kong’s frontline protesters, his arms covered with protective pads and his face obscured under a balaclava, Mr. Chan stood with a large handwritten sign held above his head. In the middle of a city park, he and a growing crowd were gathering for a mass rally on August 18.

Dressed head to toe in the black gear of Hong Kong’s frontline protesters, his arms covered with protective pads and his face obscured under a balaclava, Mr. Chan stood with a large handwritten sign held above his head. In the middle of a city park, he and a growing crowd were gathering for a mass rally on August 18.

“So peaceful that we’ll walk peacefully with you for a day!” his sign read. “Thank you for never giving up, being our backup, and for continuing to support us even if you do not fully agree with our methods!”

The sign was a nod to the unresolved internal division at the heart of the protests in Hong Kong, which have threatened to divide the movement. On one side are the “brave fighters” clashing with police on the frontlines; on the other is the “peaceful, rational, and non-violent” camp that advocates keeping confrontations to a minimum.

In a movement that has been largely leaderless, there is often no clear definition of the exact scope, direction, or strategy for the protests. So when tensions bubble up to the surface—as they appeared to in mid-August—the movement is at risk of being paralyzed by inaction, or fractured by differences. Protesters’ escalating use of vandalism and violence have also raised questions of whether their aggressive tactics will alienate more moderate supporters.

Yet here this man was, as a representative of the “fighters,” calling for unity. “We’re all Hongkongers,” said Mr. Chan, who only gave his last name. “Our beliefs are the same, what we’re fighting for is the same, though our methods may not be the same. But if we stand united, then the government will be intimidated, and we no longer need to be intimidated by them either.”

This unwavering commitment to unity, in spite of the lack of a central leadership rallying the forces, has been key to the movement’s continuing resilience since early June. Now, more than five months on, the movement’s levels of energy and solidarity remain high. If anything, the movement is more unified than ever. September saw an uptick in vandalism and the use of Molotov cocktails, yet polling showed that protesters’ tactics did not lose public support.

But tensions are particularly high after a 22-year-old student died from an apparent fall at a parking garage close to a police dispersal operation, and after an officer shot a protester at close range during morning rush hour on Nov. 11. Police and protesters were also locked in a days-long standoff at two of the city’s top universities, turning the campus into a war zone. A protracted siege at another university has seen some of the most violent clashes yet in the ongoing movement. The perennial question remains unanswered: What next?

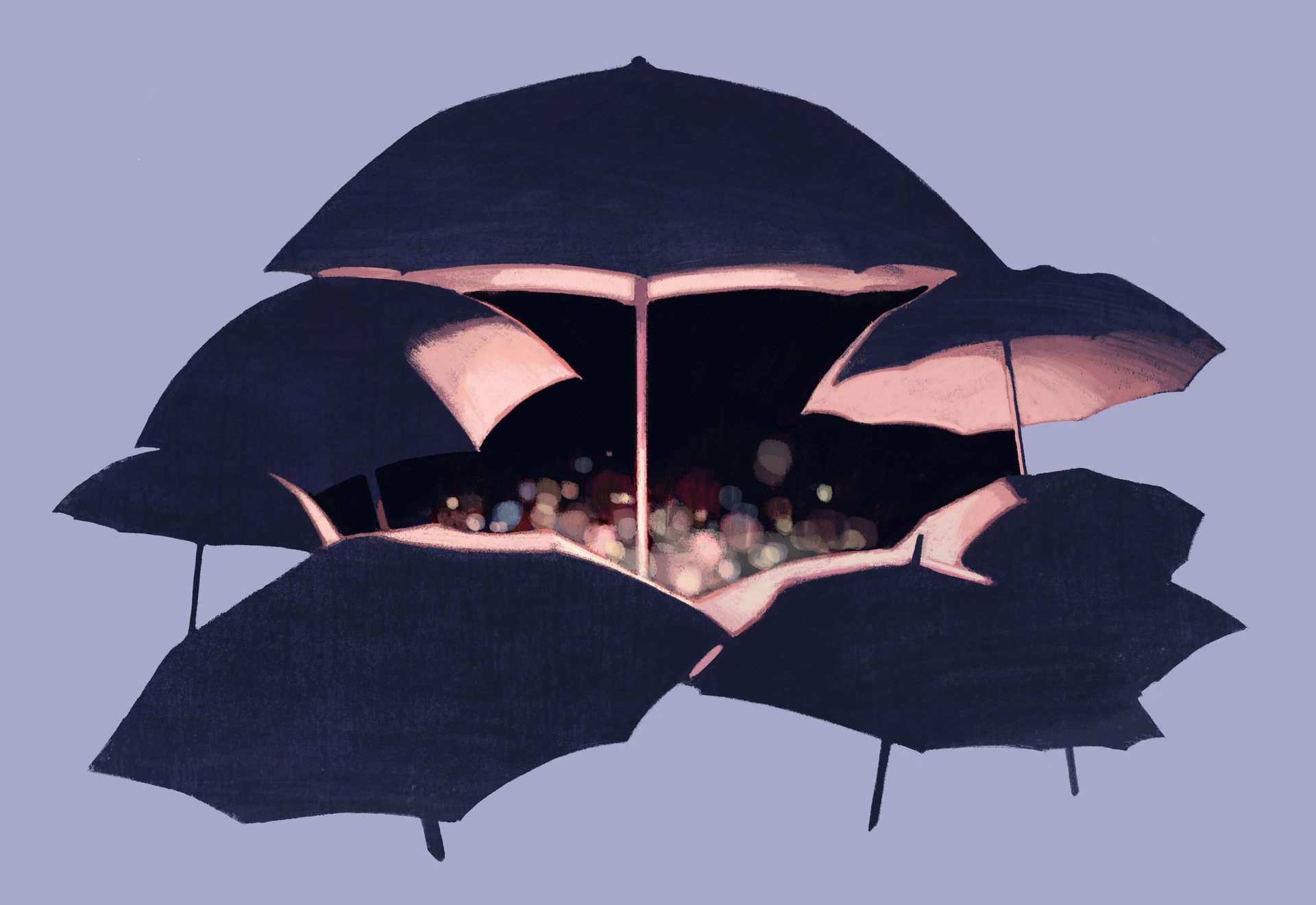

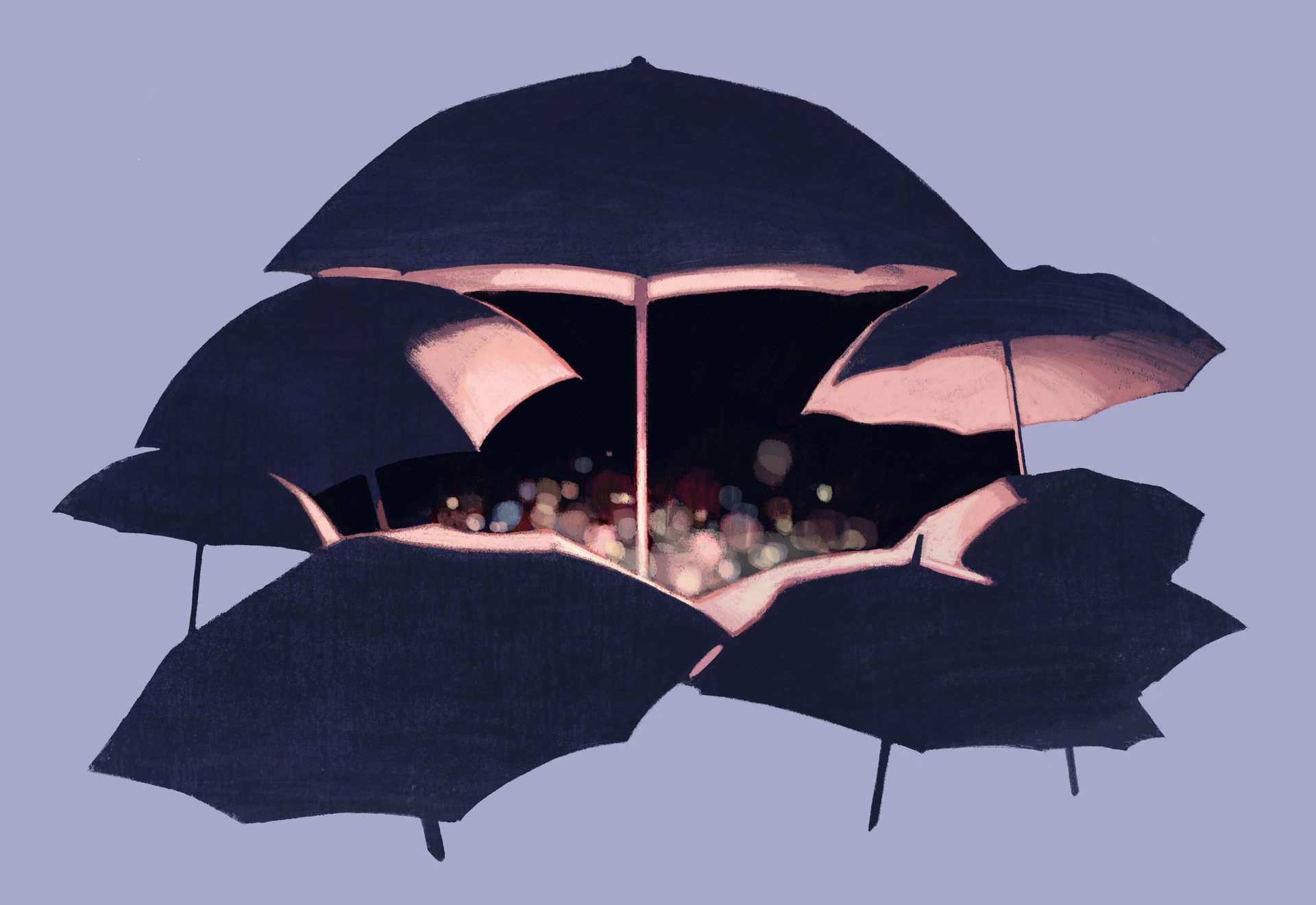

In terms of longevity, the protests of 2019 have already long outstripped the 2014 Umbrella Movement’s 79-day street occupation. But persistence is only one part of resilience. The protest movement this time around has had to endure unprecedented levels of force and violence, both from the police as well as armed thugs. A record amount of tear gas has been fired, and there are widespread allegations of police brutality, including an indiscriminate attack on civilians at a subway station in late August.

Political pressure has been similarly immense, with China releasing thinly-veiled warnings like a video of its troops cracking down violently on what look like Hong Kong protesters. Beijing has exerted pressure on companies deemed to be deviating from the party line, too, generally by penning high-profile denunciations on state media and calling for nationwide boycotts. Firms that have come under fire in recent months include the now-embattled flagship carrier Cathay Pacific, the city’s railway operator, and even a local bakery chain. In spite of these formidable threats, the protesters have managed to press on, morale and energy levels high.

A key reason for the movement’s endurance is self-starting individuals like Mr. Chan. Rather than a small number of figureheads directing from above, it’s people like him who lead, in their own small ways, from the bottom up. The absence of a clear leadership structure has given way to a greater sense of personal agency, producing a multitude of leaders.

For months throughout the summer, Hong Kong’s protesters held a dizzying array of demonstrations across the city, in what began as opposition to an extradition bill that would have allowed the city to send suspects to mainland China to face charges. Millions have attended traditional marches, sit-ins, and large rallies at parks. There have also been urban guerrilla-style battles with the police, a laser-beam rave party that doubled as a protest, and giant Lennon Walls plastered with Post-It notes across the city. The government finally withdrew the bill in early September, but to many, it’s too little, too late—a concession that should have come in June after millions marched peacefully, and before public anger coalesced around widespread allegations of police brutality. And so the protests continue.

“The very nature of the movement has been described as leaderless, although I think rather it’s a leader-full movement” said Johnson Yeung, a human rights activist who was arrested for his participation in a protest in late July. “A decentralized, leader-full movement is resilient against an authoritarian regime,” he added. “When you have a leader-full movement it’s very hard to pick a target… the movement will survive because everyone will take ownership of the movement.”

An inter-connected web of resistance

One doesn’t have to look far to find evidence of shared ownership permeating the protest movement.

Take the 38-mile-long human chain that sprang up in late August, for example. Dubbed the Hong Kong Way, it started as a short post on local online forum LIHKG suggesting that Hong Kong protesters mark the 30th anniversary of the Baltic Way, a giant human chain formed in protest of Soviet rule. Several days later, what began as a casual call to action online had materialized: More than 210,000 people joined hands across Hong Kong in a show of solidarity.

T.T., who only wanted to be identified by his initials, was just one of many volunteers who helped turn Hong Kong Way into reality. He had seen the post online, and over the next several days he and other volunteers coordinated via the encrypted messaging app Telegram to figure out logistics—promotional materials, meeting points, the exact route.

“There isn’t a great need for a very systematic or structural framework in order to achieve something,” T.T. said, noting protesters’ high capacity for strategizing and taking action as a group. “Hongkongers really know how to change and adapt, and they really quickly learned how to use LIHKG forums and Telegram for online discussions.”

One of the key reasons why Hong Kong’s protesters have been able to coordinate at such scale and duration is their sense of collective identity, said Samson Yuen, a political scientist at Lingnan University in Hong Kong who studies local social movements.

There was a gradual growth of opposition towards the extradition bill, he explained, starting with smaller-scale demonstrations in March and April and hundreds of petitions against the legislation in May, before escalating to marches of historic scale in June. “That’s why it’s so resilient: It’s simply because of the slow buildup of the collective identity” from a diverse set of participants, said Yuen. “It’s not simply Hong Kong identity we’re talking about here,” he added. “It’s more people’s everyday life identity,” such as one’s profession and neighborhood, that become strong markers of self.

That culture of protest and civic participation has actually been building up over the course of decades. Since 1989, large crowds have gathered in Victoria Park every year to remember the Tiananmen Square massacre. Every July 1 since 1997, crowds have marched to demand greater democracy; a march in 2003 marked something of a watershed as half a million people protested a national security law.

While that sense of collective identity is critical, the ongoing protests have also succeeded by amplifying individual actions. Brian Leung was one of a number of protesters who stormed the city’s legislature in early July, and was the only one to unmask himself in the chamber. He has since fled Hong Kong, but gave a speech via video link in August to an audience at a mass rally in the city. Reflecting on the protest movement so far, he identified one key takeaway: ”An important lesson is that social forces are intricately interconnected as networks. Each node of social force brings about new possibilities of further mobilization and new challenges to the regime,” he said.

The interwoven web is much like the distributed leadership structure of the protests: Each person is an intersection, and each of those vertices strengthens the overall integrity of the structure. The government can arrest dozens of protesters at a time, snipping threads in the web, but the whole thing doesn’t come crashing down because other connections prop it up. That’s resilience.

Challenges to resilience

While powerful, this informal, to-each-their-own protest movement brings with it inherent risks and vulnerabilities.

It can be difficult to find a consensus without a leading organization. Much of the movement’s decision-making has been through a form of direct democracy on LIHKG, the online forum, which functions as a kind of central command and de facto voting machine for the protesters. Making plans on such a public forum, accessible to anyone with an internet connection, opens the door to hostile actors posing as protesters and manipulating the direction of the movement.

So far, the Chinese government has failed to fully infiltrate the LIHKG community, largely because they do not fully understand the intricacies of Cantonese language structure and slang, said Yeung, the activist. But that won’t last forever.

“If this movement drags on for four months, five months, we may have to consider what platform people should use, or people should start thinking about building organizations of their own,” Yeung added. “The effectiveness of an anonymous movement can only go so far.” Part of the movement’s resilience, then, is not just improving on what has worked so far, but also being nimble enough to adapt to changing circumstances.

The rapid nature of online discussion may also encourage knee-jerk reactions, said Christian Chan, a professor of psychology at the University of Hong Kong who has written about the protests.

“This makes it easy to incite people’s emotions—and as animals, the emotions that are easiest to incite are fear and anger,” Chan said. “Fear and anger are important emotions, but they are also easily manipulated. When our decisions are driven by fear and anger, we’ll easily do things that we may regret.”

Yet perhaps the most formidable challenge to the resilience of the protest movement is not whether it is leaderless or leader-full, but rather the nature of its ultimate opponent: China.

Hong Kong’s protesters are fighting the local government, said Yeung, but at the end of the day the true force to be reckoned with is China.

“Because the Chinese regime is so strong and their legitimacy has yet to be lost, what we’re doing now in Hong Kong, rather than trying to bring systematic change…we’re actually delaying or deterring repression from the Chinese government,” he said. So long as China doesn’t embrace liberal democratic values, “then what we’re doing here is a deterring effect.”

The lingering question, though left unsaid by Yeung, seems obvious: How much does protesters’ resilience count for in the face of the Chinese state?