As the Trump administration continues to gut environmental protections, the killing of an endangered whooping crane is still egregious enough to merit federal prosecution.

In July 2018, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries got a tip that a whooping crane had been shot near a crawfish pond in Evangeline Parish. The event marked the 29th whooping crane shooting since 1967, the year the federal government listed the species as endangered.

State game wardens questioned Gilvin P. Aucoin, 52, who had been working on the property when the bird was killed the day before. Aucoin admitted to shooting the “whooper,” and his gun was seized by agents. (Aucoin works in maintenance and construction, according to public records.)

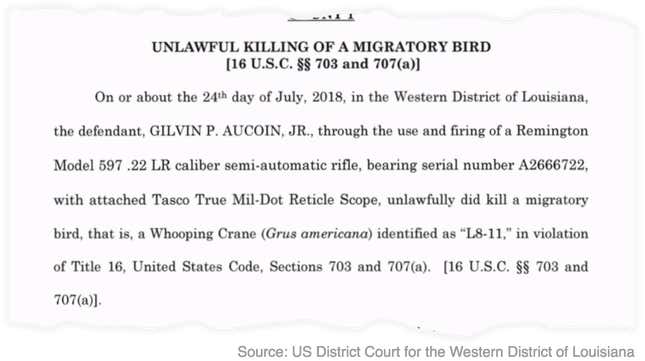

A year later, the US Department of Justice is prosecuting Aucoin under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (pdf), Quartz has found. According to federal charging documents, Aucoin shot the male crane using a Remington 597 .22-caliber rifle fitted with a Tasco True Mil-Dot Reticle Scope.

If convicted, Aucoin will face fines of up to $100,000 and one year behind bars. Efforts to reach him by phone and email were unsuccessful; three phone numbers listed under his name had been disconnected and a message sent to his email address was returned as undeliverable. He does not have an attorney listed in court filings.

A species native to North America, whooping cranes have historically been shot for sport and for their feathers, which were once used to decorate hats. Overhunting led the species to become critically endangered with a population of just 16 living birds in 1941. Over the past 50 years, the US government has spent millions to breed, hatch, and train the birds to live on their own in the wild. Today, there are about 500 whooping cranes left in the wild. Though the species’ survival is considered a major success in environmental conservation, it is still threatened by habitat loss since the wetland areas it calls home are being drained for use by agriculture and industry.

“Since humans contributed to the decline of the Whooping Crane, many people now feel that we have a moral duty to help this magnificent bird,” explains a US Geological Survey backgrounder posted to the agency’s website. “Our natural heritage of biological diversity—all of the species of plants and animals—is a precious resource. Our future quality of life depends on how we take care of our natural inheritance.”

The crane that Aucoin is accused of shooting is part of a non-migratory group that was reintroduced to the wild in 2011 and lives in Louisiana year-round. The charges were submitted by US Attorney David Joseph, a career prosecutor who president Trump nominated to oversee the Western District of Louisiana last year. A number of recent whooping crane shootings have been prosecuted on the state level; federal prosecutions, of which there have been few for whooping crane shootings, can carry heftier penalties.

Who’s doing it

Captive-raised whooping cranes began to be reintroduced back into the wild in the 1990s, according to the International Crane Foundation (ICF), a nonprofit conservation group based in Wisconsin. Since then, the ICF says most of the birds that have been killed had been part of reintroduced populations that had wandered onto private land.

“All identified perpetrators were white men with an average age of 27.6,” according to the ICF’s research. “Some of the perpetrators had prior convictions such as a citation for driving under the influence of alcohol. In six cases the perpetrators also conducted concurrent crimes, such as vandalism of property [or] shooting other non-game wildlife or game wildlife out of season. In multiple cases, alcohol was listed as a possible contributing factor.”

Nearly three-quarters of the illegal whooping crane shootings were not committed by bona fide hunters. In the handful that were, the hunters “were already in violation of a hunting regulation, such as shooting before legal hunting hours, when poor lighting makes identification difficult,” per the ICF. “In these cases, one might argue that the person was, in fact, poaching as people who violate hunting regulations are considered poachers.”

The first known Canadian shooting of a whooping crane occurred in May.

Paying the price?

It costs more than $110,000 to raise a whooping crane to adulthood in captivity and release it into the wild. But the penalties levied on those who shoot whooping cranes tend to be far lower.

In 2017, the State of Louisiana ordered a man to pay $2,500 and spend 45 days in jail for killing a whooping crane. In 2009, a female whooping crane—the first in her swoop to successfully fledge a chick—was shot and killed by an Indiana man who was later fined $1 and ordered to pay $550 in court costs.

There have only been a small handful of whooping crane shootings ever prosecuted at the federal level. The outcomes, which depend on myriad factors involving each individual case (and individual judges, who decide on sentences within a prescribed range), have been, accordingly, all over the map.

In 2004, a Texas man who shot a whooping crane was sentenced to six months in prison and barred from ever hunting again in the United States. He was fined $2,000.

In 2013, a South Dakota man was ordered to pay $85,000 (plus a $25 court assessment), and sentenced to two years probation for shooting a whooping crane. The rifle he used in the incident was confiscated, and he lost all hunting, fishing, and trapping rights for two years.

In 2016, a 19-year-old who shot and killed two whooping cranes in Texas was sentenced to five years probation, a five-year ban on hunting, fishing, or owning a gun, 200 hours of community service, and ordered to pay a $25,810 fine.

People who have worked with whooping cranes describe the majestic birds as “captivating,” calling them “a classic charismatic megafauna, like a whale or a bear or a cheetah.”

“Whooping cranes are native to Louisiana,” said one crane keeper last year. “We used to have them here, all over the place, and most people don’t even know what they look like anymore, which is rather sad.”

Aucoin is due to appear in US District Court on Sept. 24.