Leaders are gathering at the United Nations headquarters in New York City this week, where a set of climate change meetings will take place alongside the United Nations General Assembly. While they discuss ways to prevent the worst effects of climate change, the neighborhoods around the UN face a very real threat: Sea level rise is set to flood the immediate area, possibly as soon as 2100.

Right now, of every US city, New York City has the highest population living inside a floodplain. By 2100, seas could rise around around the city by as much as six feet. Extreme rainfall is also predicted to rise, with roughly 1½ times more major precipitation events per year by the 2080s, according to a 2015 report by a group of scientists known as the New York City Panel on Climate Change.

But a two-degree warming scenario, which the world is on track to hit, could lock in dramatic sea level rise—possibly as much as 15 feet. Whether it will take 100 years or longer for the total extent of the sea level rise to play out is unknown, as the rate of ice melt at the poles is harder to predict than the amount of ice that can melt with a specific amount of warming.

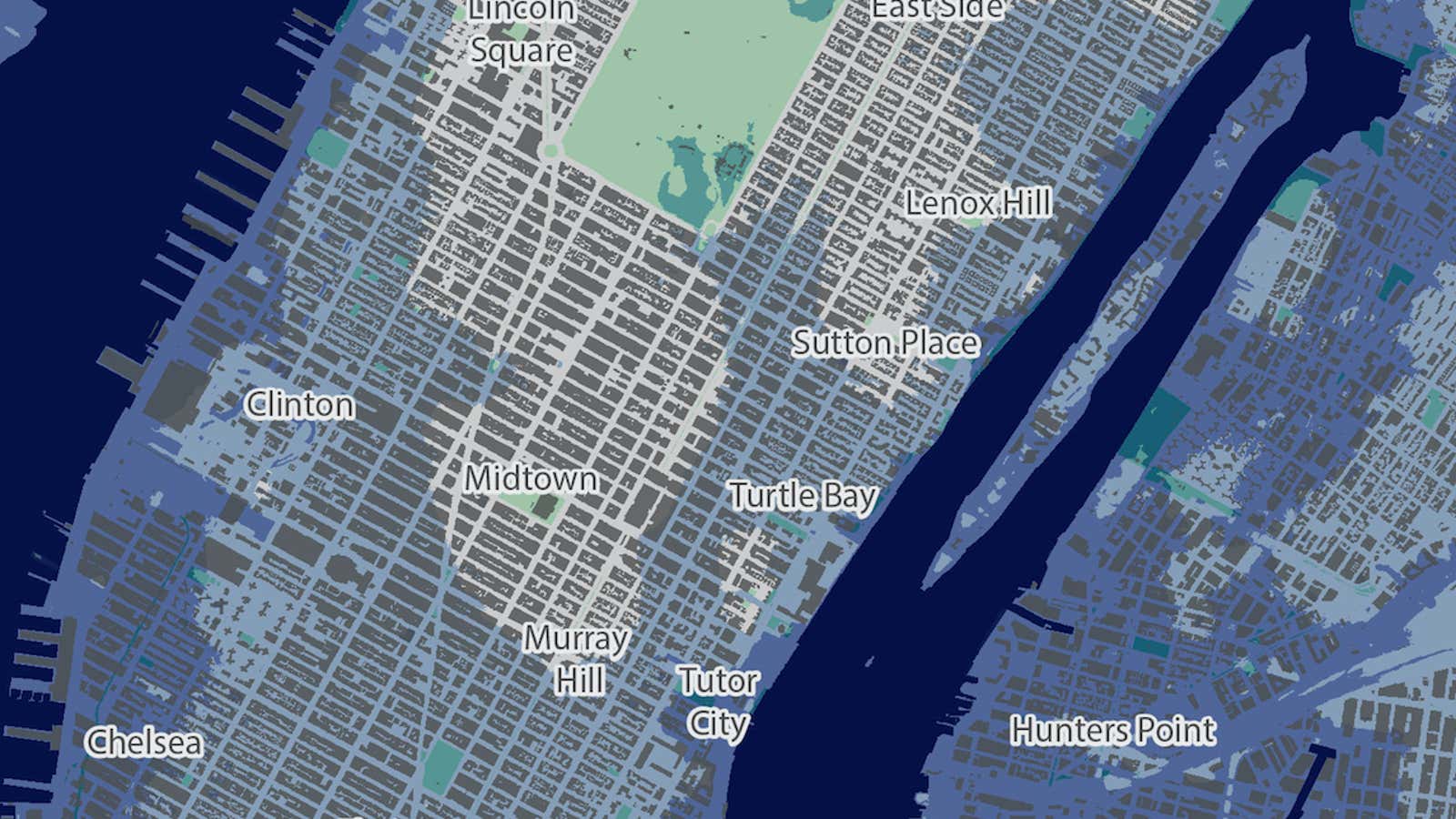

In a map built by nonprofit research group Climate Central, based on a compilation of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data and other peer-reviewed research, flooding in a two-degree warming scenario would inundate large swaths of New York City. The United Nations headquarters is located right on the coast of midtown Manhattan, along the East River. While the Climate Central maps suggest the building itself will be mostly safe due to its higher elevation, the coastal neighborhood around the UN will flood.

In other words, a building devoted to international cooperation across borders will likely be isolated by a moat.

The flooding will be far worse in other low-lying parts of Manhattan, as well as Brooklyn and Queens. The airports where international leaders might fly in to New York, like LaGuardia and JFK, would be totally submerged. Subways, too, are likely to be out of commission. When Hurricane Sandy struck New York in 2012, several subway lines were inundated, causing $5 billion in damage to the transit system. Most subway tracks are about 20 feet below ground, which means that floodwaters have the potential to penetrate the tunnels farther inland than the flood waters on the surface could, a Harvard Business School report notes. That could also wipe out the underwater transit tunnels that connect Brooklyn to Manhattan.

While leaders debate climate resiliency options at the UN building this week, it is clear that the direct threat to the city from sea level rise is no longer a question of if, but of when.

“We don’t debate global warming in New York City. Not anymore,” wrote New York City mayor Bill de Blasio in a post in New York Magazine earlier this year. “The only question is where to build the barriers to protect us from rising seas and the inevitable next storm, and how fast we can build them.”

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.