Elizabeth Warren has a plan that you may not know about.

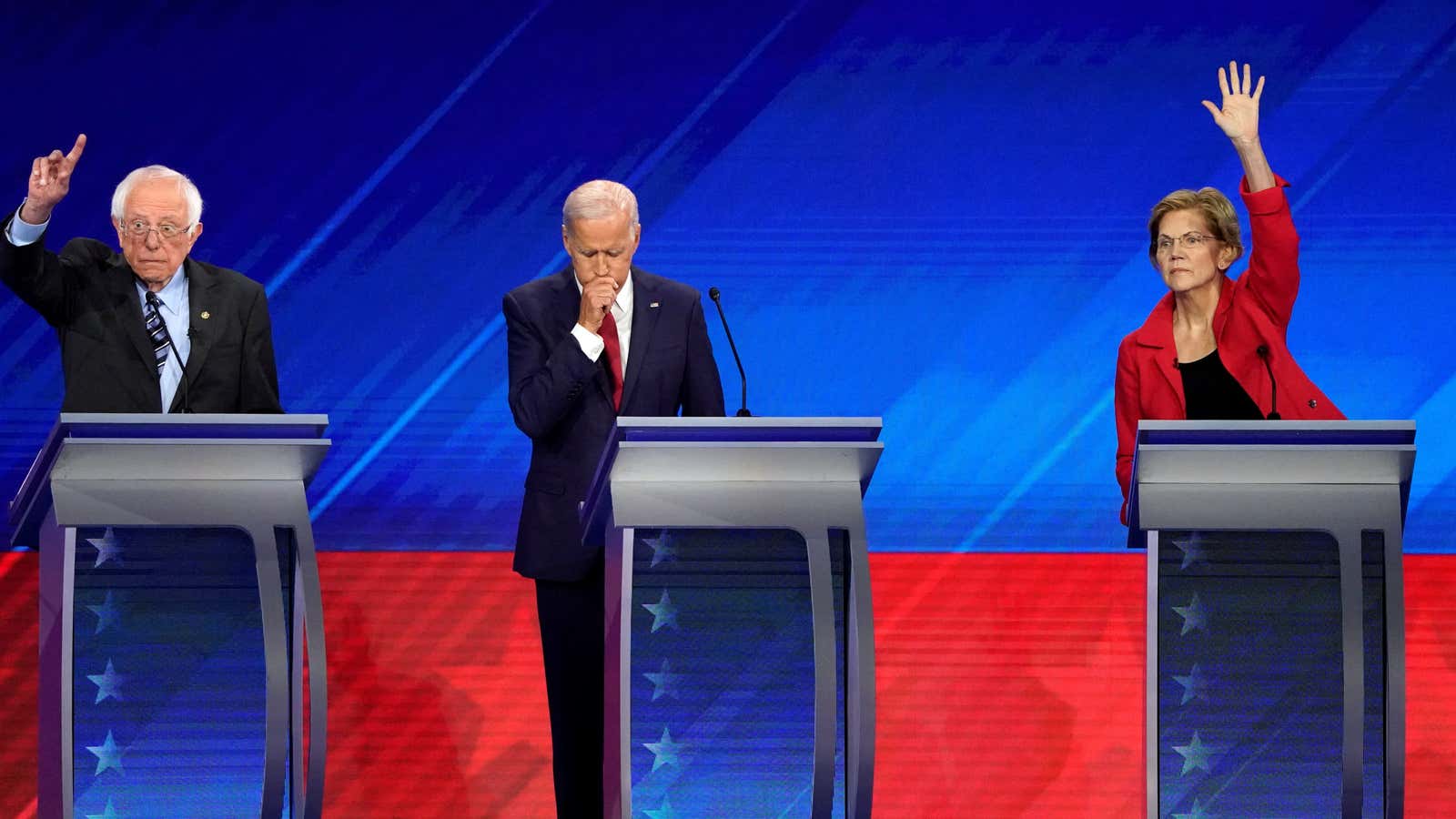

The third round of the 2020 Democratic debates in Houston showed, if nothing else, that the Massachusetts senator is proving herself to be the most viable progressive Democratic candidate.

Her recent surge in popularity among 2020 primary voters is generally thought to be owed, in part at least, to a set of comprehensive policy plans she has put forward which have set her apart from the competition with their level of detail and ambition.

“Warren has a plan for that” has become a meme, a t-shirt, and more or less her campaign’s calling card.

And why not? After nearly four years of the head-spinning chaos that has characterized the Trump administration, it seems reasonable to assume that voters might be receptive to a candidate who knows what she wants to do, and better still, can articulate how she wants to do it.

Of the many plans Warren has released, her proposal to revitalize American diplomacy has probably garnered the least attention. But given president Donald Trump’s destruction and subversion of the US diplomatic apparatus, this seems like a pretty big oversight on our part.

During Thursday’s Democratic debate, foreign policy was brought up briefly—as is more or less normal in US presidential debates. Warren spoke to her belief in diplomacy over military involvement when she stated, “We’re not going to bomb our way to a solution in Afghanistan.”

Four years of Trump’s reckless bungling makes it all the more imperative that the Democratic nominee, whoever it is, demonstrate they have both the temperament and ability to lead the country in a credible, measured, and rational manner on the world stage.

Department detox

The problem with Trump goes far beyond the president’s own vast incomprehension of foreign affairs. His appointment of Mike Pompeo as secretary of state was just one in a long line of neocons and unreconstructed war hawks appointed to influential positions within the department, including, among others, special representatives Elliott Abrams for Venezuela; Brian Hook for Iran; and Kurt Volker for Ukraine.

According to Warren, Trump has treated the department with a “toxic combination of malice and neglect” and the statistics seem to bear her out. The past four years have seen an exodus of human capital from the department. Warren charges that under Trump, “The State Department has lost 60% of its career ambassadors and 20% of its most experienced civil servants” while “nearly 15% of positions abroad have been left unfilled for years.” Meanwhile, the militarization of US foreign policy is reflected in the fact that the Pentagon budget is roughly 15 times the size of the State Department budget, and has 40 times the personnel.

To counteract this, Warren proposes doubling the size of the US foreign service and creating what she calls a “diplomatic equivalent” of the university Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) programs across the country. Warren also plans to both double the size of the Peace Corps and to open new diplomatic posts in what Warren calls “underserved areas” around the globe.

During the short interlude on foreign policy during the debates, Warren said, “We cannot ask our military to keep solving problems that cannot be solved militarily.”

She was still referring to US forces in Afghanistan.

Warren said we need a radical shift in our approach, which “means using our diplomatic efforts instead of hollowing out the state department.” But she didn’t give much more detail than that.

But there is in fact much more to her plan. In a real break with the time-honored bipartisan tradition of selling embassies to the highest bidder, Warren has previously said she will seek to end the practice of “selling cushy diplomatic posts to wealthy donors.” She pledges that she “won’t give ambassadorial posts to wealthy donors or bundlers—period.”

The reaction to Warren’s plan has been positive, for the most part.

John Evans, a retired career foreign service officer who served as ambassador to Armenia, told me he thinks Warren’s plan “is excellent because it identifies all the major weaknesses in today’s State Department and Foreign Service, starting with the gross discrepancy in power and funding between the Pentagon and state, which is largely a function of the militarization of American foreign policy that accelerated with the wars that we engaged in after 9/11, Iraq in particular.”

As he pointed out, “The vacancies, the chronic underfunding, the post closures, have weakened the Foreign Service while the spoils system that rewards campaign supporters with ambassadorships is an anachronism and shameful for a developed nation that professes to be a serious power.”

Retired colonel Lawrence Wilkerson told me that while he “heartily applauds what Warren says she would set out to accomplish, transitioning America from what is essentially an imperial policy of war, war, and more war, to a policy of diplomacy and peace, is a very tall order.”

According to Wilkerson, who served as chief of staff to secretary of state Colin Powell, Warren will face obstacles not only from Congress, which he believes is “utterly indisposed to come off the imperial writ and return to a more balanced, sane, and peaceful exercise of power,” but from within the State Department bureaucracy itself—similar to what Wilkerson said Powell faced when he tried to reform the department.

But to her credit, said Wilkerson, “Warren has found one of the critical bureaucratic places to begin: state and its instrument of national power, diplomacy. Without a revival of that instrument and of its main practitioners, the empire will continue to overreach until it chokes on its own gall.”

Policy tensions

While Warren’s plan deserves praise, the foreign policy she may pursue if elected to office may actually undermine it.

Warren, like her fellow progressive stalwart Bernie Sanders, seems to support the idea that the current world order is shaping up to be one in which Western democracies, led by the United States, must face off against Eurasian authoritarians. The “combination of authoritarianism and corrupt capitalism” is, Warren, has argued, “a fundamental threat to democracy, both here in the United States and around the world.”

As it happens, Warren is perhaps inadvertently echoing the Trump Pentagon’s “National Defense Strategy” of 2018, which elevated China and Russia as the greatest threats facing the US.

But the question of whether engaging in what amounts to a two-front cold war against Russia and China could derail her plan to revitalize American diplomacy remains open. History would suggest that such an approach would only strengthen the hands of the Pentagon, the defense industry, and the hawkish Washington think tanks which depend on the former’s largess.

Whether or not Warren’s plan will weather 2020 election season is still up in the air, of course. That said, she deserves credit for creating at least a credible plan to help the State Department recover from the ravages of the Trump years.