In the second quarter of 2019, the UK’s economy shrank. This was the first time quarterly GDP fell since 2012, according to the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS). This set off alarm bells that the UK might be slipping into a recession due to the instability and uncertainty stemming from the messy, drawn-out Brexit process.

That said, fears of a full-blown recession have receded since the ONS announced that monthly GDP grew by 0.3% in July. This means that a technical recession—often defined as two consecutive quarters of falling GDP—is unlikely. (The last time the UK experienced a recession was a five-quarter contraction in 2008-09.) Ironically, recent growth may be a result of Brexit. Ahead of the Brexit deadline—currently October 31—firms have built up stockpiles and accelerated some investments to avoid potential disruptions immediately after the UK exits the EU.

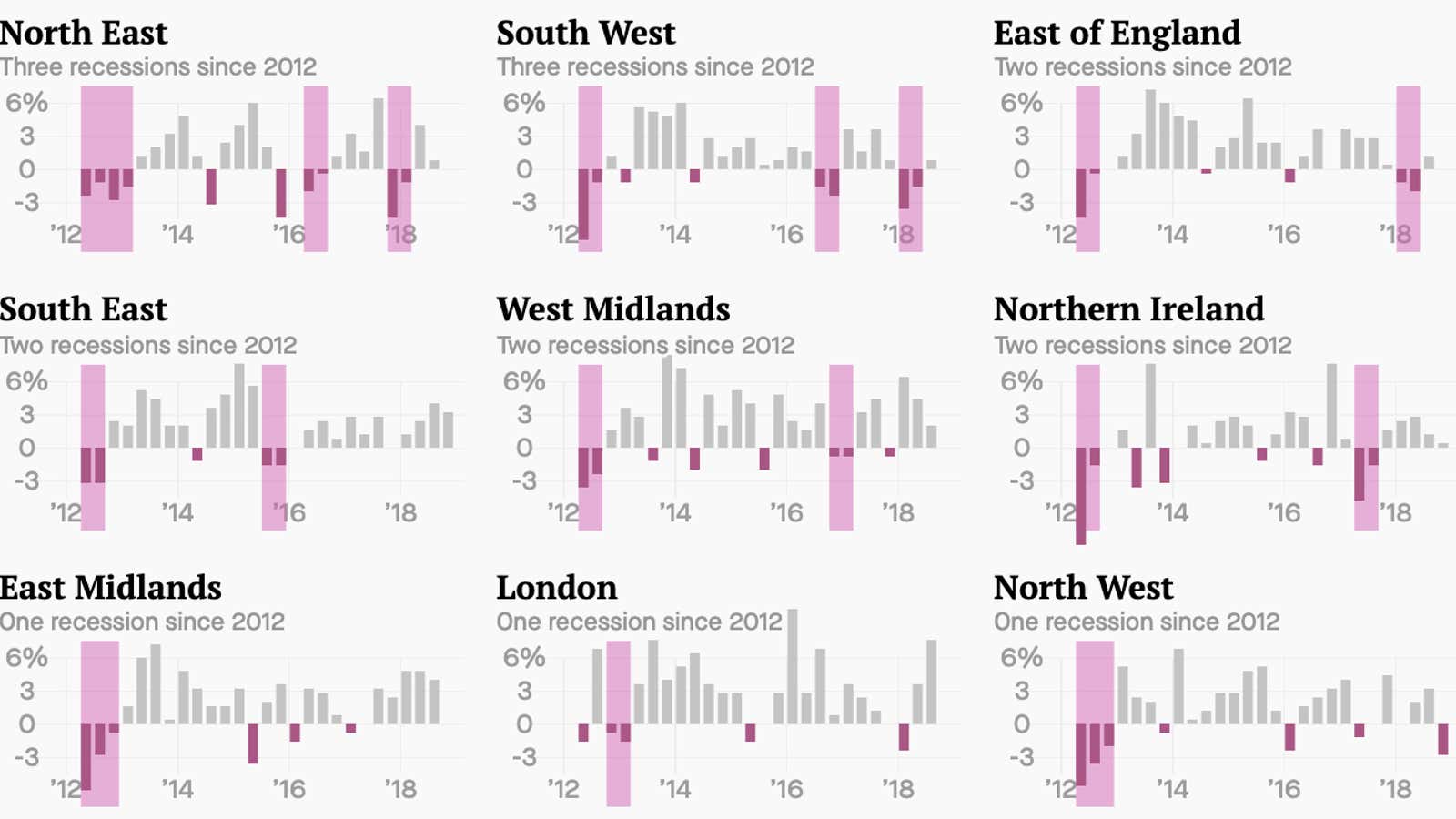

Though the UK as a whole may avoid a recession for more than a decade, that’s not true for certain parts of the country. Despite the national trend, regional economies have varied widely this decade. Of the 12 UK regions for which the ONS provides quarterly GDP estimates, 11 of them have had a recession since 2012, according to a Quartz analysis. Wales is the only exception. The North East and South West of the country have had three recessions each in that relatively short period. (All numbers are adjusted for inflation.)

The North East seems to be particularly recession-prone due to its reliance on commodities. The region, which includes the city of Newcastle, is one of the main suppliers of the UK’s oil, gas and steel industries (paywall). When commodity prices go down, so does the North East’s economy. Areas of the country with a greater dependence on services industries, like London, are less likely to experience such booms and busts. The North East is the second-poorest region of the country, after Wales, with the slowest-growing economy since 2012, so these busts are particularly harsh.

The South West, the only region of the UK that is growing slower than the North East, has experienced repeated recessions due to its unusually large trade, manufacturing and tourism sectors (pdf). Trade and tourism revenues can be unpredictable and more dependent on the state of the global economy than industries like healthcare and education.

Local recessions may matter more than national ones. That’s because in the typical region in the UK, only about 4% of the population leaves every year. If you live in Newcastle and are not willing to move, the fact that London’s economy is buoyant is not too helpful.

The UK’s regional GDP statistics lag national ones by about five months. As a result, these data may not receive as much attention as they should. A quicker turnaround on regional GDP would likely be useful as the country heads towards Brexit, helping the government direct spending towards the areas and people most at risk under the worst-case scenarios.