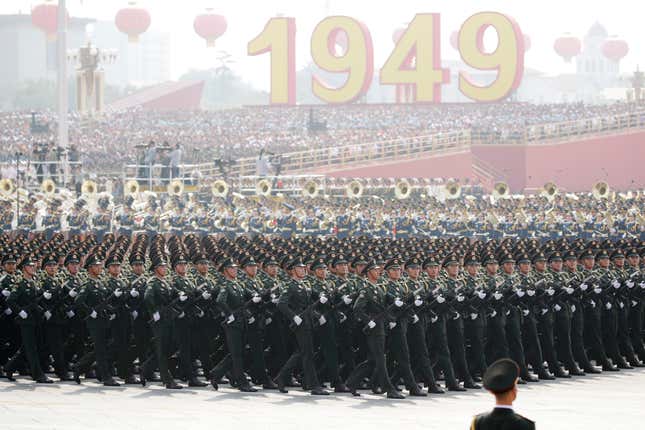

The People’s Republic of China will celebrate its 70th birthday on Tuesday (Oct. 1), with a grand military parade attended by more than 15,000 soldiers and 60,000 citizens of Beijing, a speech delivered by Chinese president Xi Jinping, and massive fireworks.

China is marking the day in 1949 when revolutionary leader Mao Zedong declared the founding of a “new China” from Tiananmen Square. The Communists, 28 years after the party was founded, had won the long-running civil war with Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang, or Nationalist forces. The Nationalist soldiers retreated to Taiwan.

Beijing needs this celebration badly. China has gone from an impoverished country in 1949 to the world’s second-largest economy, but it now faces mounting problems. These include a trade fight with the US that shows no sign of easing, a slowing economy, and Hong Kong’s ongoing protests seeking greater democracy. That makes the 70th anniversary an important moment. The government must demonstrate pride and confidence to its nearly 1.4 billion people that it can weather current challenges just as it did others, in previous decades.

Here’s a brief look at some of the most significant ups and downs during China’s 70 years as a Communist-ruled nation.

1950s: A “Great Leap to famine”

The first decade was marked by ill-fated zeal for the new country to prove itself to the world. With the goal of becoming an industrial power, the Great Leap Forward aimed for China to catch up with the UK in steel production within 15 years. In order to do that, Mao endorsed unrealistic steel and agricultural production goals for villages across China in the late 1950s. Officials who questioned his plans were beaten or imprisoned. But the raw production materials were low quality, and most of the steel was unusable. Meanwhile, food production plummeted as people were redirected to making steel. The food shortage was compounded by official lies about the figures. This led to a major famine. Anywhere between 30 million to 45 million died, some through torture, but most from hunger, and the birth rate plummeted.

1960s: Cultural Revolution chaos

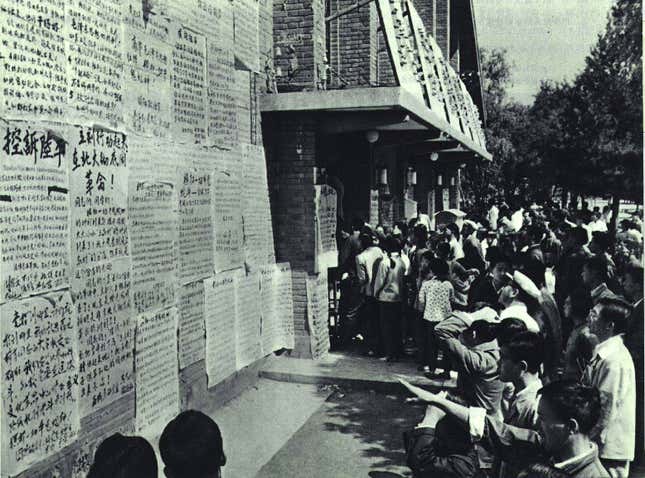

Having realized the devastating consequences of the Great Leap Forward, the Party adjusted its economic policies, but before the country could emerge from that trauma, it faced a new crisis. Feeling uncertain about his grip in power in the wake of the failed industrial campaign, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966. It was meant to consolidate power around him, mobilizing people—especially the young—to spy and report on others. Students in the Red Guards were encouraged to turn in “capitalist roaders” and “revisionists,” including their teachers and family members, for behaviors deemed disrespectful of Mao, or simply too “bourgeois.” These could include drinking a cup of coffee or not dressing in state-issued uniforms. Students also destroyed Chinese heritage to weed out the “four olds”: old ideas, old customs, old habits and old culture.

The Little Red Book became famous from this time, when the compilation of Mao’s sayings was printed in the millions and read at study sessions.

Rivals to Mao at the highest ranks of government were “purged,” including Liu Shaoqi, who had replaced Mao as the country’s chairman in 1959, partly because of the Great Leap Forward. Realizing the violence was out of control, Mao dispatched young revolutionaries to the countryside for “re-education” and used the army to restore order. Around two million people were believed to have lost their lives in the havoc that was unleashed.

Amid the upheaval, China joined the ranks of nuclear nations with its atomic bomb test in 1964.

1970s: China after Mao

The worst zeal of the Cultural Revolution abated in the early part of the decade, allowing China to make progress in diplomatic relations. China replaced Taiwan, then still under Kuomintang rule, as the official representative of China at the United Nations in 1971. A year later, Beijing welcomed Richard Nixon, the first American president to visit.

With the death of Mao in 1976, China finally got its chance to emerge from perpetual revolution. Less than a month after Mao’s death, the Party declared the official end of the Cultural Revolution. It blamed the excesses of the Cultural Revolution on the “Gang of Four”—four Party officials close to Mao, including his fourth wife—in order to avoid tarnishing the memory of Mao and perhaps the Party’s own standing.

One of those Party officials who had been purged during the Cultural Revolution emerged as China’s de facto leader upon Mao’s death. In 1978, he put China on the path to becoming the world’s factory with an unprecedented idea for a Communist country: Let some people get rich before others.

1980s: Opening up… and a bloody crackdown

This was the decade that cemented Deng’s status as the “architect of modern China” by implementing market-style economic reforms. Private businesses were allowed to develop, and foreign investment was welcomed, while maintaining the privileged status of state-owned entities.

The results were quick: In 1974, the US enjoyed a trade surplus with China—a decade later, it had started to run a deficit, one that ballooned into hundreds of billions by the current decade.

In this decade China opened up in other ways too, as economic advancement gave people the means to want more than the most basic things. A relatively relaxed political atmosphere, coupled with people’s dissatisfaction about inflation, and the death of a respected liberal leader of the Communist Party, led students to begin protesting in Tiananmen Square in April 1989. Some one million people occupied the heart of Beijing, at the height of the protests. They asked for their democratic rights . On June 4th, things took a dark turn, when tanks rolled into the square and fired on civilians. No death toll was ever confirmed but an estimate obtained by the British ambassador at the time suggests the toll may have been as high as 10,000.

China has, till this day, labelled the protests an “anti-revolutionary riot,” (link in Chinese), and maintains that the crackdown was necessary to ensure the country’s stability.

1990s: Setting up the world’s factory

Although faced with a huge global backlash over the Tiananmen Square crackdown, China carried on with Deng’s economic reforms. In 1990, Shanghai set up the country’s first stock exchange, followed by another one in Shenzhen the same year. It was a sign of China’s embrace of a freer, more internationalized economy. Moreover, a 1993 decree issued by Beijing laid the foundation for China to build the so-called “socialist market economy,” which grants private and state-owned entities certain freedoms but with heavy government intervention.

This decade also marked the return—in 1997—of Hong Kong from British rule to Chinese sovereignty. The “One Country, Two Systems” constitutional formula created by Deng would ensure the city would continue to have its own government and judicial systems. However, this framework’s effectiveness has come into question after incidents such as the 2015 Hong Kong bookseller saga that saw the city’s residents taken away by mainland agents without any official record of their actions.

2000s: The rise of a new power

After more than 15 years of negotiations, China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, an essential step for the country’s remarkable economic and trade growth in the next two decades. In addition to better access to foreign markets, WTO membership reassured international investors that China would follow international rules—although the US and other nations now say that China has not always fulfilled its obligations.

China ‘s GDP expanded by 355% between 2001 and 2010, making it one of the fastest growing major economies, according to World Bank. China successfully weathered the 2008 global financial crisis, largely through financial stimulus in infrastructure, leading to the manufacture of steel in quantities that Mao could only have dreamed of. Also in 2008, China hosted the Olympic Games for the first time, putting it on a par with its rich neighbors such as Japan and South Korea. In 2010, China surpassed Japan to become the world’s second largest economy.

2010-2019: A high-tech society

This period saw China’s transformation from a “world factory” to an innovation hub that has cultivated a number of tech powerhouses with global influence. These include e-commerce giant Alibaba, gaming mogul and WeChat operator Tencent, as well as fintech giant Ant Financial. A group of aspiring Chinese startups have also emerged amid investors’ surging interest in spotting the next unicorn. One of these is ByteDance, parent company of short-form video app TikTok. It is valued at more than $75 billion and has a global presence.

Xi Jinping, who was elected the general secretary of the Party in 2012, and president of China in 2013, has taken the nation in a more nationalistic and authoritarian direction. Under him, dissent, including those from within the Party, is being silenced more quickly. Meanwhile, cutting-edge technological tools are deployed to monitor and clamp down on groups such as the Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang.

But along with the rise of the tech giants, have come mounting uncertainties. A hawkish Trump administration has increased tariffs on hundreds of billions of Chinese goods and put China’s tech national champions such as Huawei on a black list. China has adopted similar retaliatory measures. Both countries’ trade negotiators are scheduled to have another round of talks this month. However, a recent Bloomberg report said the US could delist Chinese stocks, which has darkened the prospects for a trade truce in the near future. The ongoing unrest in Hong Kong, meanwhile, is also likely to mar celebrations in Beijing, as protesters in Hong Kong are expected to take to the streets that day, chanting anti-China slogans and taking aim at symbols of Beijing’s control.