The Steve Jobs speech that made Silicon Valley obsessed with pirates

In January 1983, Steve Jobs gathered a group of Apple employees at an off-site retreat in Carmel, California. The group was in the midst of developing the Mac, the company’s hugely ambitious personal computer—and some employees felt the project was losing its scrappy spirit. And so Jobs offered a maxim meant to motivate the developers: “It’s better to be a pirate than join the navy.”

In January 1983, Steve Jobs gathered a group of Apple employees at an off-site retreat in Carmel, California. The group was in the midst of developing the Mac, the company’s hugely ambitious personal computer—and some employees felt the project was losing its scrappy spirit. And so Jobs offered a maxim meant to motivate the developers: “It’s better to be a pirate than join the navy.”

This wasn’t about treasure maps and eyepatches. “Being a pirate meant moving fast, unencumbered by bureaucracy and politics,” software engineer Andy Hertzfeld, an original member of the Macintosh team, tells Quartz via email. “It meant being audacious and courageous, willing to take considerable risks for greater rewards.”

The pirate metaphor also involved a certain willingness to plunder. “Steve also never minded occasionally stealing good ideas from others, like the Picasso quote—’good artists copy, great artists steal,’” Hertzfeld adds.

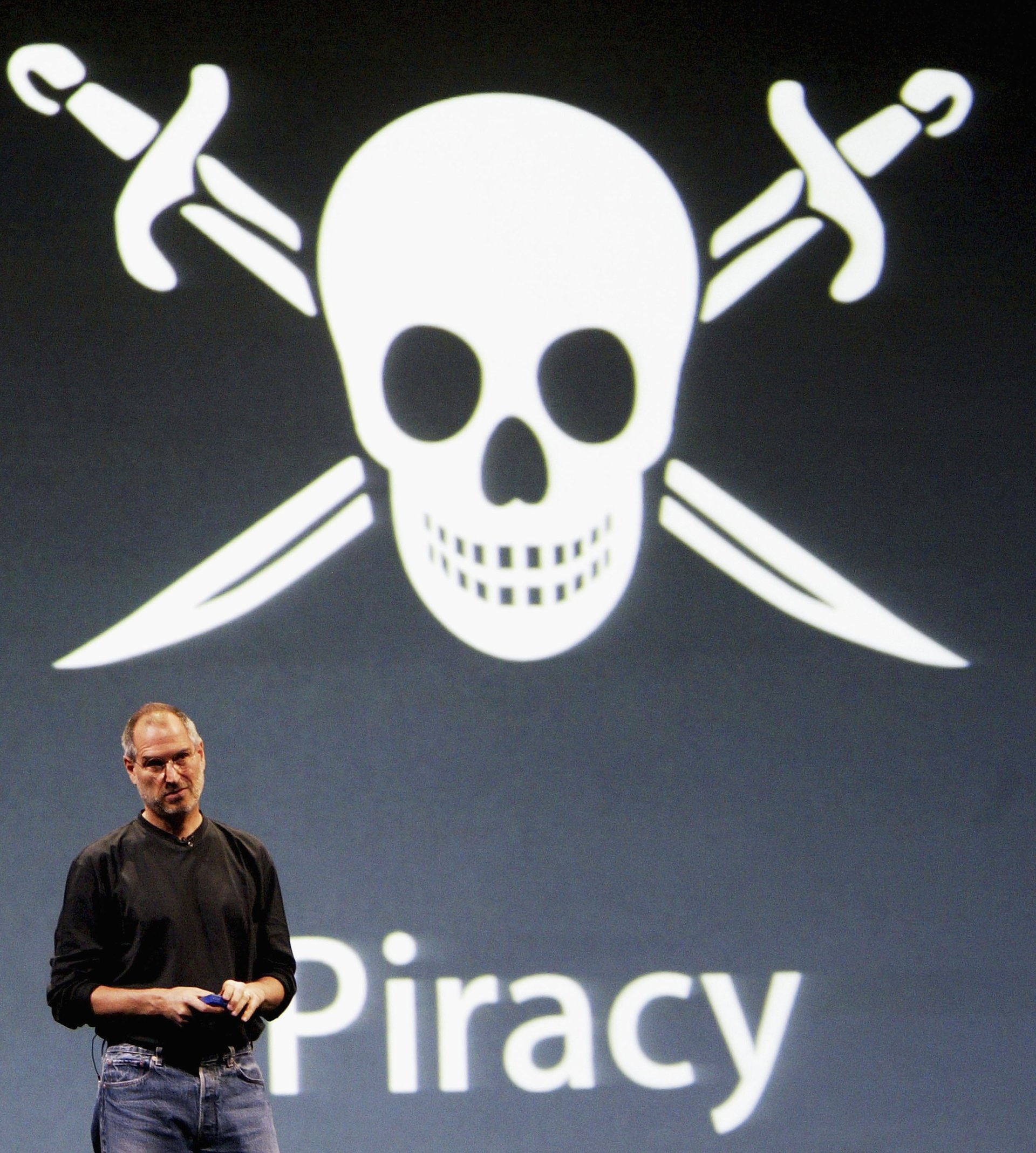

For the Mac team, the message stuck. When they moved to a larger building some months later, in August 1983, they even ran up their very own pirate flag, painted by Mac graphic designer Susan Kare. It featured the traditional skull and crossbones with a twist: “The final touch was the requisite eye-patch, rendered by a large, rainbow-colored Apple logo decal,” Hertzfeld recalls on his website.

The tale of the pirates would come to symbolize the anti-establishment ethos of Apple’s early history. In 2014, Kare began selling hand-painted pirate flags on her website in two sizes, which are now available for $3,500 or $5,000 each. Kare was inspired to sell them after receiving an email from a new Apple employee who wanted one to hang in his cubicle. “In his email, he told me, ‘I didn’t come to Apple to join the damn Navy,’” Kare told Fast Company. “So he wanted the flag to remind him of why he came to the company in the first place.” On the company’s 40th anniversary in 2016, a pirate flag flew proudly over its Cupertino headquarters.

“The company never sought to operate like a pirate ship,” Hertzfeld tells Quartz, noting that large organizations need structures and rules to run smoothly. “The essence of Apple’s identity was always innovation at the intersection of art and technology, which really has little to do with pirates.”

But symbols have a way of taking on a life of their own—and in the decades since, hordes of hoodie-clad tech workers and startup founders have latched onto Jobs’ aphorism. The story of how, and why, pirates became the unofficial mascot of Silicon Valley offers insight into the particular style of bold, countercultural entrepreneurialism that shaped contemporary tech culture—and eventually fueled the public backlash against it.

A pirate’s life for them

Cultural touchstones like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, and the contemporary Pirates of the Caribbean movie franchise have helped form our romantic view of pirates as fun-loving renegades and tricksters. They’re not necessarily the world’s most upstanding heroes, what with all the pillaging and mutinying and walking of planks. But the rum-swigging, “Yo Ho”-singing pirates of pop culture are wily survivors and masters of their own destinies. They live outside the bounds of both the law and the daily grind.

“Pirates represent being part of a powerful subculture,” Alexa Clay, co-founder of the League of Intrapreneurs and co-author of the 2015 book The Misfit Economy: Lessons in Creativity from Pirates, Hackers, Gangsters and Other Informal Entrepreneurs, tells Quartz. “Implicit in that, in this whole ethos, is being the underdog, agility, and entrepreneurialism; being a bit of a rebel or a renegade where you might have to break some rules and you’re operating outside of the boundaries of protocol.”

While Jobs’ piece of pirate wisdom was specific to the context of the early Mac team, it became legend for Mac devotees. A 1994 issue of MacWorld mentions the pirate story at least three separate times, calling the hoisting of the pirate flag “a mainstay of Mac mythology” and referencing Jobs’ pirate pep talk as emblematic of the Mac designers’ mission to make a machine for “free-thinking, discriminating nonconformists and rebels like themselves.” In essence, as the Mac computer attained cult status, people naturally repeated tales of its creation. The pirate story seemed to reaffirm the cheeky, anti-establishment reputation that Apple cultivated and with which Mac fans identified.

To be fair, being a Mac fan in the 1980s and 1990s really was a nonconformist move. Microsoft controlled (pdf, p.70) 49% of the personal-computer market share by 1985 and 90% of market share by 1995, while the Mac never nudged above 12% market share during that period.

To be a “Mac person” was to opt out of mainstream consumer choices. Apple’s marketing leaned heavily into the idea that the people who both created and used its technology were outsiders. In the very first TV commercial for the 1984 Mac, Apple depicts a young woman wearing a tank top with the Macintosh logo literally smashing the gospel of conformity (as embodied in a Big Brother-like talking head on a TV screen) with a sledgehammer. Similarly, in a 1997 commercial for the Apple computer, images of cultural icons like Bob Dylan, Albert Einstein, and Martin Luther King, Jr., flash across the screen while a voice intones, “Here’s to the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in a square hole, the ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules, and they have no respect for the status quo.” Rebels made Apple computers, and rebels bought them, too.

As Pui-Yan Lam explains in a paper on the cult of the Mac, published in the Sociology of Religion (pdf), there’s a reason why people seemed to so fervently identify with Apple and its upstart persona. Because personal computers were, as MIT professor Sherry Turkle put it in her book The Second Shelf: Computers and the Human Spirit, “an object to think with.” People who chose to invest in a Mac often saw their choice as a reflection of how they thought and how they saw the world.

Lam explains that IBM was perceived in the 1980s as “the symbol of uniformity, bureaucracy and authoritarianism,” while in the 1990s, Microsoft’s Gates was viewed by Mac acolytes as a symbol of money-grubbing mediocrity. In contrast, Apple loyalists built a group identity predicated on their shared conviction in a way of living in which fluidity and freedom were prized over rigidity and stasis. This was bound to resonate among people dissatisfied with the “greed is good” Wall Street ethos of the 1980s. And it was a classic example of how marketing and branding can both shape and reinforce consumers’ sense of self, just as Nescafé instant coffee appealed to housewives’ sense of duty to their husbands in the 1950s, or the Volkswagen Beetle tapped into the burgeoning counter-cultural movement in mid-century America.

And so the generation of future engineers and entrepreneurs who would shape the startup boom of Silicon Valley in the 2010s came of age with the understanding that it was cool to like Apple, the idealistic underdog, and to try to emulate Jobs. Googling the phrase “lessons from Steve Jobs” yields 121,000 results, a mere 27,000 less than Jesus. “The entire valley is driven by the goal to emulate Jobs,” technology journalist Mike Elgan wrote in a 2011 post for Cult of Mac, while a Wired article that same year called Jobs “the greatest CEO in memory.” And if you wanted to be like Apple and emulate Jobs, then you probably read up on stories about the Mac’s earliest days, and found yourself thinking a lot about pirates.

The lure of the “buccaneering spirit”

Jobs’ pirate metaphor has been used in everything from hiring advice to executive coaching. A 1999 docu-drama about Jobs and his sometime-rival, Bill Gates, was titled The Pirates of Silicon Valley. More recently, LinkedIn co-founder and venture capitalist Reid Hoffman devoted an episode of his podcast (pdf) to expounding upon the pirate metaphor, explaining, “early-stage startups are a lot like pirate ships. Pirates don’t convene a committee meeting to decide what to do—they strike quickly, break rules, and take risks. And you need this buccaneering spirit to survive when the cannonballs are flying and the odds are against you.”

MailChimp CEO and co-founder Ben Chestnut readily backed up Hoffman’s claim, chiming in on the podcast, “Oh my God, when you’re a startup founder, it’s all pirates. Who joins a startup? Crazy people, because startups are so risky. They’ve got a chip on their shoulder. They’ve got something to prove. They don’t want rules.”

Airbnb co-founder Joe Gebbia has also drawn on the pirate metaphor to explain his company’s attitude toward experimentation, telling First Round Review, “You go be a pirate, venture into the world and get a little test nugget, and come back and tell us the story that you found.”

Meanwhile, the grassroots “Pirate Summit,” created by a group of entrepreneurs in 2010 and billed as the “craziest startup conference” for early-stage companies, takes place in Europe every year. TechCrunch founder, entrepreneur, and venture capitalist Michael Arrington also wrote back in 2010 about why pirates serve as a useful metaphor for the startup world’s appetite for risk and adventure, writing, “The potential for riches was just an argument for the venture. But the real payoff was the pirate life itself.”

But what are the implications of Silicon Valley’s pirate ethos? Some historians have made much of the fact that pirate captains were democratically elected, and that pirate contracts typically divvied up booty fairly evenly between higher-ranking officers and regular members of the crew. But Mark Hanna, associate professor of history at UC-San Diego and the author of Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740, notes that pirate ships were hardly ideological utopias.

For one thing, he notes, “the history of piracy is actually trying to compel other people to do things.” Pirates were pressed into signing contracts in part so that they’d have skin in the game; if you know that there’s documentation saying that you’re an official member of the crew, that means you could get hanged if you’re caught—which makes you likely to fight harder when the navy is trying to catch you.

Moreover, Hanna says that by and large, pirates were “not very good to women.” Pirates often raped women; to note just one disturbing and awful example, one pirate crew took over a Danish ship transporting women who had been captured as slaves and christened the ship “Batchelor’s Delight” (pdf). Unfortunately, Hanna observes, there’s a clear parallel between pirates’ treatment of women and modern-day stories of rampant sexual misconduct in the tech industry: The tech industry, as he explains, “is not exactly famous for being progressive.”

There are plenty of other unflattering parallels to be drawn between pirates of yore and Silicon Valley as it’s developed over the past few decades. Both involve a lot of heavy drinking. Both offer what Hanna calls the “impression of a wondrous exciting life, which in the majority of circumstances is not true.” Just as pirate lore centers on the quest for treasure, so too does Silicon Valley startup culture place a premium on striking it rich by becoming the next billion-dollar “unicorn.”

And ultimately, both pirate ships and Silicon Valley companies need hierarchies and structure in order to function properly. This is something that Hertzfeld says Jobs, and early Apple employees, were always aware of. “Apple never really had a pirate mentality,” he says, noting that “good ethics are of paramount importance” and that “large organizations need structures and rules and they are by definition more like the navy than pirates.”

But if Apple knew better than to attempt to emanate pirates for real, the startups that emerged in its wake, inevitably influenced by Jobs and his legacy, have not always been so discerning.

When ethics walk the plank

Uber is perhaps the ultimate case study in the pitfalls of conducting business the way fantasy pirates would. Under the leadership of its co-founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick, Uber plunged headlong into myriad scandals involving everything from sexism and sexual harassment to its unapologetic flouting of laws and regulations to Kalanick’s explosive temper. Uber’s story, which eventually led to Kalanick’s ouster as CEO, is a cautionary tale of how easily rock-n-roll, rule-breaking bluster can turn toxic. As Hoffman explains on his podcast, when the pirate mentality goes too far, “you can tip from a culture that joyfully flaunts orthodoxy, to a culture that truly believes that winning is all that matters, and ethics be damned.”

Uber’s current CEO, Dara Khowsroshahi, is much more of a navy man, with a steady, by-the-book approach. As Quartz’s Ali Griswold suggests, “boring is just what the company needs.”

The foibles of companies like Uber have awakened Silicon Valley to the dangers of tossing the rulebook entirely out the window. Some of the metaphors that once served Silicon Valley, motivating its entrepreneurs and engineers to achieve their current state of cultural dominance, simply aren’t applicable today.

“Maybe in the 1980s, before Silicon Valley became a full-blown success, they were the underdogs,” Clay says. But as she points out, citing Anand Giridharadas’ argument in Winners Take All, “we’re continually promoting that myth of them as underdogs when they have enormous power and privilege.”

Once, perhaps, it wasn’t so wild for tech workers and founders to envision themselves as pirates. Many of the people who helped build Silicon Valley were hippies, eccentrics, and amateur hobbyists who prided themselves on operating outside of the institutions that had a lot of money and influence. David Packard and William Hewlett really did start their company out of a garage in 1938. A band of engineers known as the “Traitorous Eight” defected from their overbearing Nobel laureate boss, William Shipley, in 1957, in what was effectively a modern-day mutiny. They started their own company, Fairchild Semiconductor, which would go on to invent the integrated circuit and enable the mass production of silicon chips. Margaret O’Mara writes in her history of Silicon Valley, The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America, that Fairchild “established a blueprint that thousands followed in the decades to come: Find outside investors willing to put in capital, give employees stock ownership, disrupt existing markets and create new ones.” That sounds pretty close to the pirate ideal.

But those people who once prided themselves on being outside the mainstream? They’re defining the mainstream now, reshaping everything from the nature of childhood to the structure of commerce and US national politics. And as Clay points out, “as much as entrepreneurs dress themselves up as pirates, often they’re white, they’re male, they’re young, they’re well-connected to privilege. So how much of that is counter-cultural?”

In his podcast, Hoffman suggests that there comes a time in the life of every startup when it’s time to shift from thinking like pirates to thinking like the navy. But it may be that, even early on, there’s a cost to envisioning oneself as a pirate—in that the metaphor allows entrepreneurs to gloss over the realities of their privilege, and circumvent the self-reflection that would require them to grapple with the power many of them wield from the get-go.

What kind of companies might be built if their founders started from a different kind of premise; if they thought of themselves not as swashbuckling renegades chasing a life of adventure and riches, but as artists, or scientists, or public servants? The Valley’s self-image, it seems, is due for a system update.