Silicon Valley has managed to alienate both sides of the political spectrum. On the left, Democratic senator Elizabeth Warren intends to break up companies like Google, Facebook, and Apple. “Today’s big tech companies have too much power—too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy,” she wrote on Medium. On the right, House member Tom McClintock has accused Google and Facebook of “practicing censorship and political favoritism” (mostly while moderating threats and hate speech on their platforms), articulating the new conservative battle cry. During Mark Zuckerberg’s congressional testimony last April, Republican senator John Kennedy warned the CEO: “I don’t want to vote to have to regulate Facebook, but by God I will.”

Big tech appears to be taking the threats seriously, going on a lobbying spree that saw five companies—Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft— spend $64 million in 2018, as well as sending executives to appear before congressional committees.

But don’t be fooled by appearances. Despite the Valley’s newfound unpopularity in Washington, the tech giants feel like they hold the upper hand, and their clout is only growing. Five of the world’s largest firms are US technology companies headquartered on the West Coast. Giants like Google, Amazon, and Apple all enjoy favorability ratings above 60%, according to a Gallup poll last year, while Congress’ approval rating hovers around 20%. Tech’s influence reaches deep into the White House: Google’s former executive chairman Eric Schmidt and PayPal founder Peter Thiel have enjoyed direct lines to Barack Obama and Donald Trump, respectively.

To date, lax regulation has allowed Google, Amazon, and Facebook to build their empires at lightning speed and at massive scale. All of the platforms have avoided much scrutiny of their underlying business model—collecting data on users’ every move, micro-targeting for advertising—as well as engaging in alleged anti-competitive behavior by suppressing rivals (pdf) and competing products (paywall).

Big tech is now using its wealth and power to do more than shape regulation of its activities. It’s influencing policy far beyond its narrow self-interest. Channeling the idealism that spawned many of these companies in the first place (remember’s Google’s founding credo, “Don’t be evil?”), this new class of global companies wants to reshape society in its image. By their reckoning, the world should look more like the digital economy: fast-paced, innovative, open to rapid failure, and disruptive. The conservative assumptions that guide our government, in this view, do not match the pace of technological change.

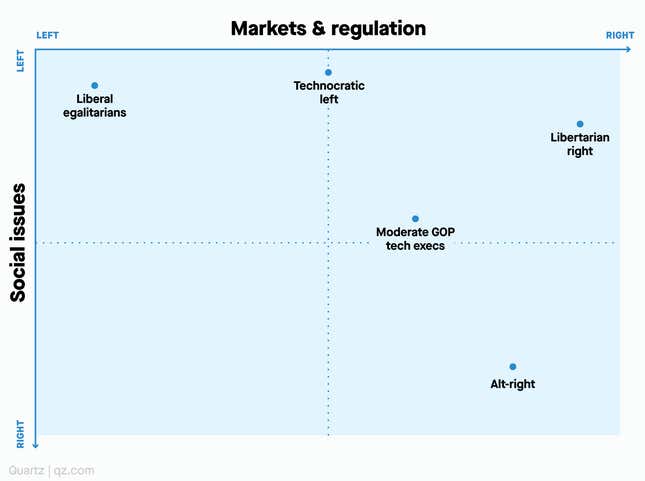

But Silicon Valley doesn’t adhere to a one-size-fits-all political ideology, and classifying its politics has stumped pundits for years. Are they Atari Democrats? Pro-innovation liberals? Liberal-tarians? In reality, Silicon Valley is an uneasy mix of laissez-faire capitalism and social progressivism that would feel familiar to the Nordics. The primary competition is among liberals. Since the 1990s, Silicon Valley has broken hard for Democrats, a trend that has only accelerated (Hillary Clinton trounced Donald Trump in the Bay Area during the 2016 presidential election, with 73% of the vote). While Silicon Valley’s base cheers on social justice efforts, it is suspicious of the digital economy that is powering rising inequality and their own prosperity. Meanwhile, tech executives and founders share the social sentiments of their employees, yet hold views on market regulation and unions (less of both, please) that look a lot more like the Republican donor base.

This conflict in the Valley’s politics mirrors a key struggle within the Democratic party. Democratic socialists like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez command a growing wing of the party (and could one day the White House) and want to curb tech leaders’ agenda of less regulation and more “creative destruction” in the US economy. Mainstream Democrats, like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, have doubled down on Silicon Valley’s model of economic growth. Clinton’s “unprecedented” outreach to the tech industry in the 2016 campaign led to policy proposals ranging from forgiving startup founders’ student debt to creating a national bank for broadband infrastructure. Of all the groups vying to influence the future shape of the Democratic party, tech entrepreneurs are expected to be among the most influential, according to a recent survey (pdf) of 1,100 partisan donors by researchers at Stanford University.

Figuring out which views are ascendant—and most likely to prevail—requires analyzing the different factions shaping the US political and policy agenda. Quartz has sorted through decades of political spending data and interviewed dozens of people to map Silicon Valley’s rival political camps.

Table of contents

The technocratic left • Liberal egalitarians • The libertarian right • The lost tribe of Republican tech execs • The alt-right (light)

The technocratic left

Who’s in this camp?

- Sam Altman, investor, entrepreneur, and chairman of venture fund Y Combinator

- Paul Graham, co-founder of Y Combinator

- Co-founder of LinkedIn Reid Hoffman

- Former Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt

- Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg

- Tesla CEO Elon Musk

- Mark Pincus, co-founder of gaming company Zynga

- Union Square Ventures investor Fred Wilson

What do they believe?

From Google to Facebook to Y Combinator, these liberal technocrats love big government—as long as it’s not regulating them. On social issues, they are as progressive as you can get. They see big government as the best way to supply education, achieve a basic standard of living for everyone, redistribute society’s wealth to maintain social cohesion, and fund basic research and development for groundbreaking technology down the line. Popular policies include Medicare for all, free college tuition for civic service, and a universal basic income.

While some may feel the pace of technological change is too fast, this group sees it as far too slow–even as technological adoption accelerates. If it doesn’t speed up more, they argue, society will not generate the jobs and wealth it needs to ease society’s transformation from an industrial economy to a digital one. They want the government to play a large role in tempering capitalism’s threat to social stability along the way, but they’re firmly focused on their vision of human progress driven by technology.

Their views diverge strongly from the rest of the Democratic party on economic policy when it comes to regulation (they’d prefer as little as possible) and unions (they want more labor flexibility). That combination of views is unique in the US, according to a 2018 study in the American Journal of Political Science. The entrepreneurs it surveyed support globalization, tax redistribution and liberal social stances (same-sex marriage, gun control, and abortion rights) at levels similar to most Democrats in the US.

Their hostility toward regulation and government interventions in markets most closely mirrors that of the Republican donors. That puts them out of the mainstream of any US political party.

That divide broke out in the open last year at the California Democratic party convention in San Diego. Democratic speakers called Elon Musk a “union-busting asshole,” as tech lobbyists passed out pamphlets trying to derail support for laws such as the California Consumer Privacy Act, a tough new data privacy law. They failed. The bill was signed into law by California’s governor last June.

Trump critic and venture capitalist Fred Wilson summed up this group’s view on regulation in the age of Trump at a 2017 conference. As he was bashing the president, he said tech may ultimately benefit from his presidency because “anarchy is good, and regulation is bad. And honestly, that’s good for tech….. I’m not for anarchy. I’m willing to pay the tax that good regulatory oversight creates on our industry. But really, I think if done right now, it [regulation rollback] would be good for tech.”

The technocratic left fiercely opposes Trump’s nationalist and populist agenda. It’s anathema to Silicon Valley’s global values (even, they admit, if he’s pointed out legitimate problems his supporters care most about such as declining blue-collar economic opportunities, a corrupt political class, and overweening political correctness). Altman, for example, has called Trump “an unprecedented threat to America…[who] shows little respect for the Constitution, the Republic, or for human decency.” Musk, who eventually left Trump’s business advisory councils over his decision to exit the Paris climate agreement, publicly tweeted his disapproval of the president, and said: “I think Hillary’s economic policies, her environmental policies in particular, are the right ones.”

To flex their muscle, this group is starting to donate enormous amounts of money. Hoffman founded Win the Future to rebuild the Democratic party, in partnership with Pincus of Zynga, and said his political spending may eventually reach hundreds of millions of dollars. Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz gave $20 million to help Democratic candidates win in the 2016 election, and has continued funding Democratic priorities through the most recent midterm elections.

Favored candidates:

A few moguls have toyed with running for office. Mark Zuckerberg’s tour of the US (and subsequent hiring of Democratic pollsters) fueled rumors he was running for office. Altman briefly considered, and then thought better of running for governor of California (“I don’t think charisma is my strength,” he said). But if this group has a standard bearer, it’s a candidate like Andrew Yang, the 44-year old former tech company founder and populist firebrand who’s campaign motto is “Humanity First.” He supports a universal basic income and Medicare for all, is a celebrity on Reddit, and doesn’t subscribe to the “capitalist/socialist dichotomy,” the idea that a market economy can’t coexist with a strong Nordic-style safety net. Oh, and he wants to save us from artificial intelligence.

This group demands results, and backing mainstream politicians has been the best way to push their agenda, much of which still falls under the Democratic banner (Yang is polling about 1% nationally right now). According to political science researcher Greg Ferenstein, Michael Bloomberg was among the highest polling candidates among Silicon Valley CEOs when he was contemplating a presidential run in 2016.

Some of the biggest beneficiaries of this group’s largesse, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, have been Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Dianne Feinstein, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, and even the National Republican Congressional Committee. Schmidt, former executive chairman of Google and later Alphabet, helped lead Obama’s and Clinton’s digital campaign efforts by building their voter-targeting operations and celebrated Obama’s 2012 election night victory at the president’s Chicago campaign headquarters.

Liberal egalitarians

Who’s in this camp?

- Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff

- Employees of Silicon Valley tech giants like Google, Apple, and Microsoft

What do they believe?

Egalitarian liberals see the economy working primarily for the 1% and want to see a more socially equitable society. Many working in Silicon Valley, ironically, see the tech sector as one of the main culprits of the winner-take-all economy, and they want to change the rules.

The composition of this group spans from tech’s rank-and-file to billionaires like Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff. In a metro area with the third-most billionaires in the world, this sentiment helped Bernie Sanders outraise (paywall) Hillary Clinton by millions of dollars in 2015. The employees of its biggest companies like Google, Apple, and Microsoft were on his side, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics, which estimates such companies accounted for about half of the top 20 employers donating to Sanders’ campaign. Manfred Georg, a 33-year-old software engineer at Google told the Wall Street Journal that “I want things to be fair and I feel the system, as it is, is not.”

“Tech has come of age,” says Dilawar Syed, former president of the customer support startup Freshdesk who organized a pledge signed by prominent tech founders, investors, and executives to resist Trump Administration attacks on civil liberties. “Employees have unprecedented power and willingness to speak up.”

This leverage over their bosses was on the mind of Brad Taylor, a former Optimizely software engineer, when he formed Tech Against Trump in January 2017 to organize protests on tech campuses. Later that year, thousands of people did walk out on tech campuses across the Bay Area over Trump’s policies, particularly an immigration ban on seven Muslim-majority countries. Pressure from employees is a key factor in executives thinking on politically charged topics, says one former Obama official. “So many of my conversations with technology companies have led to the response: ‘I’ll have to see what our engineers will say about that,” he said. “I’ve never heard a telecom say that.”

But the last two years have been a tough lesson in electoral politics. The Valley has limited leverage over the Trump Administration, and activists say walk-outs have revealed the limits of their influence over policy. They’ve had more success at home: Google employees succeeded in pressuring the company (paywall) not to renew a contract with the Defense Department to design artificial intelligence for interpreting video, although companies like Amazon and Microsoft are still pursuing such contracts.

Executives are taking activist stances on social issues as well. The most visible is Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, who has made his positions felt nationwide. Benioff threatened to pull Salesforce out of states such as Georgia and Indiana in 2016 for attempting to pass laws allowing religious organizations to deny jobs, social services, or educational opportunities by citing “sincerely held religious beliefs” related to same-sex marriage. Benioff also campaigned hard last year to pass Proposition C forcing San Francisco’s biggest companies to pay taxes to fight homelessness.

Benioff has become a template for tech executives to become activists. When campaigning to pass Proposition C, he told MSNBC last year, “there were no CEOs on my side, I was the only CEO.” But since its passage, more executives have stepped up. Twilio and Airbnb have donated millions to address homelessness in the city. Companies “finally have the permission to help,” said Benioff, “and that’s coming from their employees.”

Favored candidates: Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Kamala Harris—crusading candidates that seek to root out injustice and reduce inequality—are the patron saints of this group. The three candidates top fundraising totals from employees of big tech companies.

While corporate donations are split relatively evenly between the two parties, tech employees give overwhelmingly to Democrats. In the most recent election, employees at top tech companies gave 91% of their donations to left-leaning candidates (see chart below, ranked by the aggregation value of donations). This follows the pattern from the 2016 presidential election when Clinton got 95% of the $8.1 million from tech employees or executives, and Donald Trump only got 4% (Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson and Green Party Jill Stein each got less than 1%, reports FiveThirtyEight). Barack Obama, Cory Booker, and local representative Ro Khanna all figure high on this list.

Some Republicans benefit as well. Benioff has given his fair share over the years to Republican candidates such as Paul Ryan and the Republican leadership re-election PACs, while directing more money to Democrats in recent years. His largest donation was a $25,000 contribution to the Ready for Hillary political action committee in 2013. But he has distanced himself from any one political party to focus on progressive issues. Speaking at the NationSwell summit on April 25, Benioff described his journey from a Republican working as co-chair of a technology advisory committee under President George W. Bush’s in 2003 to liberal firebrand without a party.

“I’m a lifelong Republican who become an independent after I tried doing something in government,” he told the audience. “I can’t serve one political party. I’m not a Republican or a Democrat. I’m just an American. I don’t want to affiliate [with one party]. I want to affiliate with ideas.”

The libertarian right: Divided by Trump

Who’s in this camp?

- Peter Thiel and early PayPal employees (the “PayPal Mafia”)

- Oracle founder Larry Ellison, Oracle executive Safra Catz

- venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale

- Founder Fund investor Keith Rabois

- Uber CEO Travis Kalanick

- VR startup Oculus co-founder Palmer Luckey

- Investor Scott Bannister

- Cypress Semiconductor founder TJ Rodgers

- Silicon Valley libertarians who haven’t backed Trump

What do they believe?

Silicon Valley is the libertarian stronghold of the popular imagination, but libertarian party candidate Gary Johnson barely eked out 3%, just above his national average, while democratic socialist Bernie Sanders outraised Clinton in fundraising dollars.

Historically, Silicon Valley’s conservative libertarians have advocated for a vision of American society in which entrepreneurs are free to pursue different ways of organizing society and maximizing technological innovation. Their vision, says Mitch Stoltz, a senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, involves ignoring Washington more than negotiating with it. “Conservatives exist within Silicon Valley as libertarians,” he said. “That strain is very much still present.” He describes their philosophy as: “We can build an online future that’s faster and more powerful than any government can keep up with. We can go online and in a certain sense, secede.”

Trump has split conservative loyalties. Some, such as early PayPal employee and venture capitalist Keith Rabois, consider Trump disqualifying on practical and ethical grounds. He’s called the president an “incompetent” leader who has “nothing to do with the conservative movement.”

Very few have become public supporters of the president in Silicon Valley. “I know of exactly two Trump supporters,” Marc Andreessen said of tech elites’ support for the president during a podcast in 2017, presumably referencing billionaire Peter Thiel and Oculus founder Palmer Luckey (a professed libertarian who gave $100,000 to Trump’s inaugural committee).

Thiel has emerged as Trump’s biggest backer in tech. In 2016, Thiel gave Trump $1 million for his bid to win the White House, then addressed the Republican National Convention as a Trump delegate and served on Trump’s transition team. Staffers from Thiel-affiliated companies have gone on to executive branch positions in the FDA to the Office of Science and Technology Policy. “I cannot overstate [Thiel’s] impact on the transition,” Bannon told Vanity Fair at the start of the administration, suggesting he might hold a role in US intelligence. Although that never happened, Thiel’s company Palantir scored major contracts with America’s military and intelligence establishment, and former chief of staff Michael Kratsios is now in line to be the next US chief technology officer.

Thiel shares Trump’s public disdain for out-of-tech elites and institutions. Trump is an opportunity to call out and stop what Thiel sees as the loss of America’s individualist, free-market ethos favoring business. “One thing I’ve heard Thiel say about why he likes Trump is that he was the only one sufficiently pessimistic about America,” says Samuel Hammond, a policy analyst at the libertarian-leaning think tank Niskanen Center. Thiel may see Trump as a way to return the US to a lightly regulated state of unfettered capitalism. “Resistance to change in Washington, D.C. has been even fiercer than I anticipated” Thiel lamented in 2017. “We still need change. I support president Trump in his ongoing fight to achieve it.”

Others, like Oracle founder Larry Ellison, appear to be pursuing narrow corporate interests, as they have with other presidential administrations. Without as many activist employees as Google or Facebook (Oracle never experienced walkouts), the company has stood by the president, refusing to sign an amicus brief with other tech companies slamming Trump’s immigration ban on Muslim countries, hiring Trump’s disgraced National Security Council aide Ezra Cohen-Watnick, and talked with the Trump administration to place Oracle co-chief executive Safra Catz in a cabinet role. Similarly, former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick (who once posted the cover of Rand’s novel The Fountainhead as his Twitter avatar) never seemed to be a fan of Trump, but was willing to serve on one of his advisory boards until the criticism grew too intense.

Yet even Thiel’s attitude toward Trump has soured over time. Since the election, Thiel has reportedly declined any government appointments, privately called Trump “incompetent” to friends, and put the odds of Trump’s administration ending in “disaster” at 50%, reports Buzzfeed.

Favored candidates: Traditionally, this group backed a mix of mainstream Republicans—Mitt Romney, Eric Cantor, and former Missouri attorney general (now Senator) Josh Hawley—as well as far-right politicians such as Freedom Caucus founding member Justin Amash and Texas Senator Ted Cruz. A few Democrats, such as Ro Khanna, have also received donations. Thiel was the first major break with the party establishment giving $1 million to Donald Trump after donating $2 million to former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina’s failed presidential bid a year before.

The lost tribe of Republican tech execs

Who’s in this camp?

- ex-CEO of Cisco Systems, John Chambers

- Intel CEO, Brian Krzanich

- Andreessen Horowitz’ ex-head of policy, Ted Ullyot

- Hewlett Packard Enterprise CEO Meg Whitman

- Sun Microsystems co-founder Scott McNealy

What do they believe?

There was a time when tech executives could hold a fundraiser for a Republican presidential candidate without raising an eyebrow. Not anymore. In June 2016, when Intel CEO Brian Krzanich scheduled a fundraiser at his house for “a full exchange of views” including then-candidate Trump, the news rocked Intel, whose employees accused Krzanich of betraying the values of the Intel’s immigrant founder Andy Grove. Krzanich canceled the event and took to Twitter to deny backing Trump.

With partisanship affecting even the highest levels of corporate America, politically moderate, Republican-leaning executives have found themselves adrift. Traditionally, executives have used political donations to candidates as a way to maximize their influence within a new political establishment and minimize the risk of regulation. Personal politics were not often the deciding factor. That changed with Trump. Immigration, family separation, discrimination against transgender Americans, and a host of other assaults on progressive values forced corporate chiefs to take sides. For those unwilling to do so, such as Intel’s Krzanich, they have tried to sever any explicit connections with Trump and redirect support to the Republican party apparatus instead.

Favored candidates:

- Mitt Romney and supportive PACs

- NeverTrump PAC

- National Republican Senatorial PAC

- Democrat Ron Wyden (active on tech issues)

The neo-reactionaries and the alt-right (light)

Who’s in this camp?

- James Damore

- Curtis Yarvin (aka Mencius Moldbug)

- Vox Day

What do they believe?

Supporters of the extreme alt-right likely don’t have many adherents in the Valley. That hasn’t stopped the movement’s most noxious figures from claiming them. “The average alt-right-ist is probably a 28-year-old tech-savvy guy working in IT,” claimed white nationalist Richard Spencer in 2016. “I have seen so many people like that.” As head of the white nationalist National Policy Institute, Spencer needs to inflate his support, especially among the tech elite. In spite of the headlines, there is no evidence supporting the claims that the Valley is a hotbed of right-wing extremists.

That’s not to say some of their beliefs don’t have traction there. The Valley’s far-right tends to hold highly intellectualized positions associated with the “neoreactionary movement,” or “Dark Enlightenment.” One of its central figures, Curtis Yarvin, writes under the pen name Mencius Moldbug. The programmer (whose company Urbit was funded by Thiel’s venture fund) believes society took a wrong turn at the Enlightenment and we should return to feudalism or an absolute monarchy. Headlines on his posts include, “Why I am not a white nationalist” and pose questions such as “What’s so bad about the Nazis?”

Less extreme are people like James Damore. In 2017, the former Google engineer penned a 10-page manifesto titled “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber.” It purported to show the gender gap in tech was partially caused by innate biological differences between men and women, and accused Google of unfairly favor women and minorities when hiring. Google later fired him for creating a harmful workplace for women. While denying any connection to the alt-right (he calls himself a “classical liberal”), Damore quickly became a rallying figure for the movement. He staged a publicity tour with its most popular online personalities and posted a fundraiser on WeSearchr, a site created by Trump booster and prominent alt-rightist Chuck Johnson, to raise more than $50,000 for “financial and potentially legal assistance.”

For Damore and his ilk, the persecution complex is key to their identity in the Valley’s liberal milieu, says Hammond of the Niskanen Center. “They basically feel like they’re in hiding all the time,” he says. But the far-right’s presence in the Valley is meager, enjoys no political support on the ballot, and is most notable for enjoying visibility that’s disproportionate to its actual influence.

A reckoning

The debate playing out in Silicon Valley is an almost perfect microcosm of the larger debate playing out in America: how to reconcile two thus far opposing priorities: socially progressive views and a radical free market. Calling them liberal or libertarian or conservative misses the point. While the vast majority of its residents and workforce are Democrats, traditional liberal ideals (such as building strong unions and regulatory bodies) are fracturing as new political coalitions form.

Just as the technology Silicon Valley created has radically changed how we live, we should expect Silicon Valley’s battle to define the rules for our changing society to leave an indelible mark. Will the technocratic left reshape US policy by marrying a generous welfare state with minimal regulation of startups? Or will the egalitarian ethos ascendent in the Democratic party mute Silicon Valley’s clout over the economy.

That story is still playing out. But one thing we can all be sure of: This is about far more than how to balance pro-technology regulatory policies and the public interest. Silicon Valley executives and employees may never agree on regulation, but with a few exceptions, they profess the same desire for a multicultural society, a generous welfare state, and a system that works for everyone, and they’re spending their money and influence on making those America’s priorities too.

As the region’s political power grows, expect this to be the defining political battle in Silicon Valley, and in the Democratic party itself.

Correction: The story has been updated to reflect that Google’s motto is “Don’t be evil” rather than “Do no evil.”