More than 70,000 people die of a drug overdose in the United States every year. In 2018, the majority of those deaths (almost 50,000) were from from taking opioids. And the majority of opioid deaths were from the synthetic kind, like fentanyl.

People die of overdoses in other rich countries too, but not nearly as often.

In 2013, overdose deaths accounted for 12% of the difference in life expectancy between American men and men in other wealthy countries. The overdose mortality rate in the US is on average 3.5 times higher than those same countries, and twice as high as they are in northern European countries—which have the second-highest rate of overdose deaths among that group.

But with no country is the comparison more mind-boggling than with Italy. Overdoses in the US kill 27 times the number of people per 100,000 they do in Italy. And that’s not because Italy doesn’t have a drug problem: The country is among the top five in Europe for so-called problematic drug users (PDU) (pdf, p.14), or people who routinely abuse intravenous opiates.

It’s because, since a heroin epidemic in the 1980s, Italy has become a pioneer in tackling drug addiction. And a big reason for its success is simple: the availability of a drug called Naloxone.

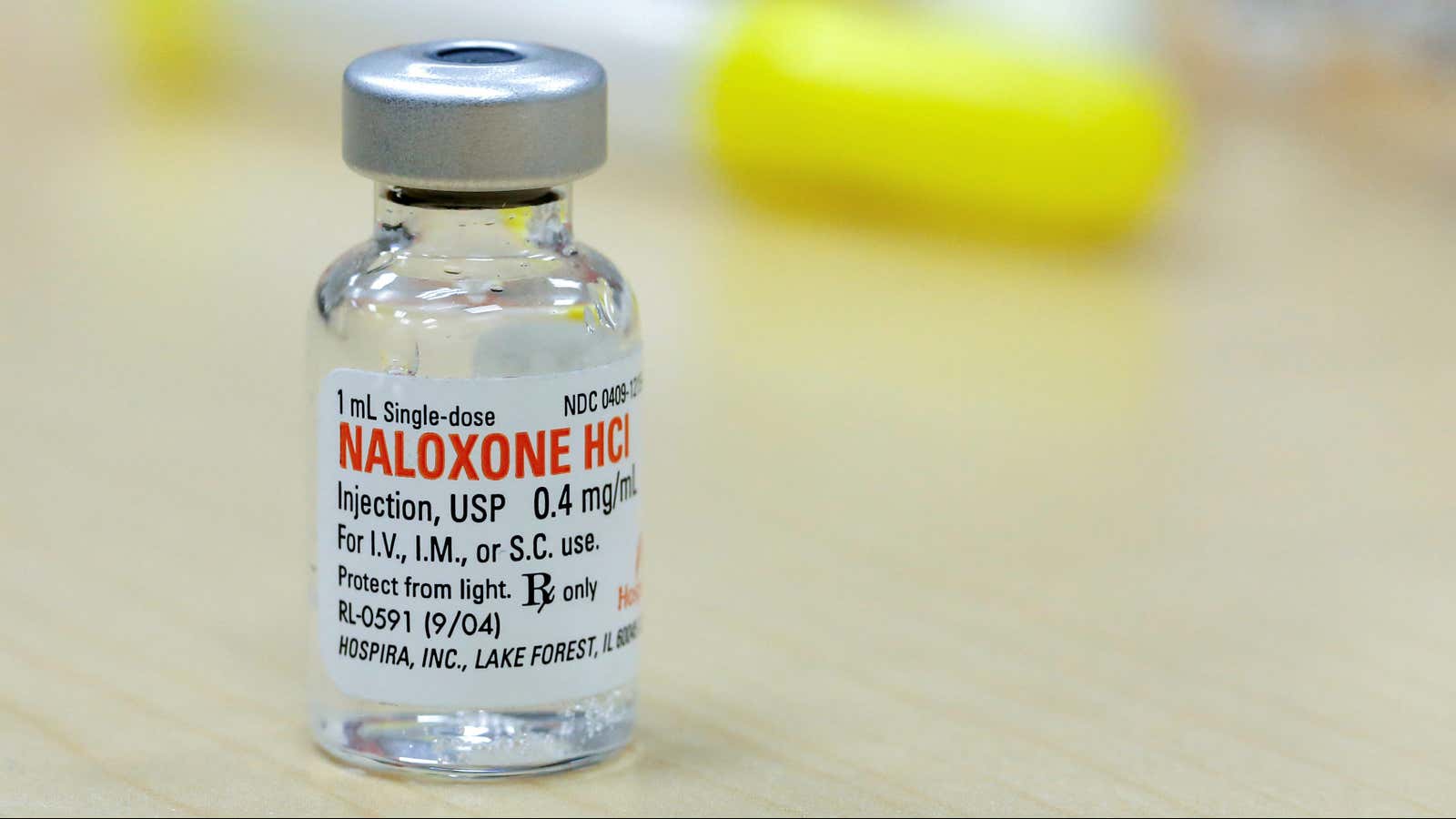

Naloxone is an emergency drug used to counter the respiratory arrest caused by an opiate overdose. Such breathing issues can quickly lead to brain damage, if not death. But Naloxone—which is available either as an injection or a nasal spray—can immediately relieve those symptoms. It only works if there are opioids in the person’s system, and researchers say the drug has no other effect and causes no damage.

Naloxone is available in the United States, but only with an expensive prescription. In the last two decades, meanwhile, Italy has not only made Naloxone available over the counter, it has—in combination with other harm reduction services—distributed it directly to drug users and their circle of friends and family. The program is known as Take Home Naloxone, or THN.

The program was started after Italy’s department of health realized that making the drug available over the counter in pharmacies was insufficient. Many drug users didn’t feel comfortable buying it, or have the resources to buy it. So doctors and health workers began distributing Naloxone to both drug users and the communities around them, training them to recognize an overdose and administer the drug. According to the World Health Organization, opioid users have a 50% to 70% lifetime risk of having an overdose. But they are also very likely to be present during someone else’s overdose.

Where is the US at?

The Harm Reduction Coalition, an American nonprofit that tackles drug abuse by reducing its negative effects rather than focusing exclusively on eliminating the abuse, recognizes the importance of distributing Naloxone directly to at-risk communities. There have been some efforts to do just that. The largest program was “Dope” in San Francisco, which trained 13,000 people to carry and use Naloxone. But outside of such isolated efforts, the United States has been stuck where Italy was prior to the 1990s.

The problem begins and ends with the federal government. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hasn’t cleared Naloxone to be sold over the counter, let alone distributed freely in the streets. And while the FDA is considering allowing Naloxone to be purchased without a prescription, it is only available in its nasal or self-injectable forms, which are far more expensive than vials and syringes. Naloxone in nasal spray form is about 10 times more expensive than it is in its traditional form, costing about $75 a dose. Self injectables are even more costly.

While some critics say the free distribution of Naloxone is a safety net for drug users and could actually encourage drug use, physicians have largely debunked that belief.

“We are pushing hard for the standard formulation (vial and syringe) to be available over the counter,” Kiefer Paterson, a government relations manager at the Harm Reduction Coalition, told Quartz. “It’s the only type that is scalable.”

But as Italy now knows, that’s not enough.

Paterson said federal and local authorities are purchasing sizable quantities of Naloxone, but they are distributing it primarily to first responders and emergency personnel, even though they are rarely the first to be present during an overdose. It is also typically made available in the nasal spray form because it’s easier to use and due to a general discomfort among officials with syringes, Paterson said. That makes it all more expensive.

It’s an ineffective allocation of resources, both in terms of who is given the drug, and the form in which it’s given it. “This explains why even if we are spending a lot of money on Naloxone, we aren’t seeing as much of it being used,” Paterson said, adding that other drugs, like insulin, are available as a syringe and over the counter. “People who inject drugs typically don’t have problems with needles.”

While the US has a long way to go still, the Italian example shows that even a little effort can have a big impact.

Take Naloxone Home programs in Italy aren’t actually that extensive, either. While there are now 57 groups distributing the drug around the country, they don’t come even close to servicing all of the country’s many urban centers. Entire regions of Italy, in fact, remain uncovered. Naloxone can also be hard to find in pharmacies and some resistant pharmacists still demand prescriptions for it. Yet even against these odds, Italy has managed to reduce the number of deaths from opiate overdoses to less than a tenth of what it was at the problem’s height in the 1990s.