Art Lien didn’t dream of becoming a courtroom sketch artist, though his name did hint at this ultimate destiny.

In fact, it’s a job Lien once mocked. The NBC News and SCOTUS Blog Supreme Court illustrator was reluctant to even admit what he did for a living in the beginning, so low is the news sketcher in the esteem of artists.

He got into the business in Baltimore in 1976 because he needed the money. Lien had graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art and was tarring roofs for a time. But he quickly rose to the top of the court art trade trade, becoming the high court illustrator for CBS in 1978.

At that point, every American news outlet had a sketch artist and work was plentiful. Now, Lien is among the last of a dying breed, a rare and endangered species.

Lien is a witness on behalf of the people. By “going where the cameras cannot,” he sees for the people in a place where the electronic eye is barred by law. He is part of a tradition of live illustrative court reporting that started in the 19th century and continued in American tribunals until the 1980s when states started allowing filming.

Federal courts maintain the ban, though that’s bound to change eventually. In the postmodern age we are enchanted by the camera and film is considered more real than reality.

So Lien has no illusions about the fate of the quaint tools of his trade—papers, pencils, and watercolor paints. The artist’s days in court are numbered, he says.

The observer effect

Last month, the House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the public’s right to accessible courts and considered the use of cameras in federal legal proceedings. The technology is currently banned, in part because of the observer effect.

Observation changes the way observed matter behaves. That’s true in physics and in life. The observer effect, as applied to people, is much more dramatic in the presence of cameras.

Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts put it as follows at the University of Minnesota Law School in 2018, “I think if there were cameras that the lawyers would act differently. I think, frankly, some of my colleagues would act differently.” Roberts contended that televising proceedings in the US Senate had changed hearings for the worse, substantively. But he acknowledged that the public would benefit from courtroom cameras. The chief justice explained:

People have an absolute right to know what we’re doing and that’s true in courts around the country. I think it is to a certain extent unfortunate that we are not televised because I think most people would be pleased with what they saw in terms of how seriously we take our work and the high level at which the exchange is conducted. But I do think it would have an adverse affect on our job under the Constitution and that has to come first.

Lien only partly agrees with the chief justice. His sense is that people would be impressed by the court’s gravity and the complexity of the questions justices tackle. He acknowledges that cameras would surely change proceedings, but is not certain it would be for the worse. The change might be good.

Eye of the beholder

Lien got his first court gig by sketching reporters in a newsroom. Other artists competed for the job but he won, was promised $40 a day, and got fired immediately. He came to court with “all the wrong materials.” Paint pooled on his nonabsorbent paper, marring the images, and the editor rejected his work. The artist went back, unpaid, experimenting with cardboard instead. The images stayed fixed and Lien unwittingly discovering his calling.

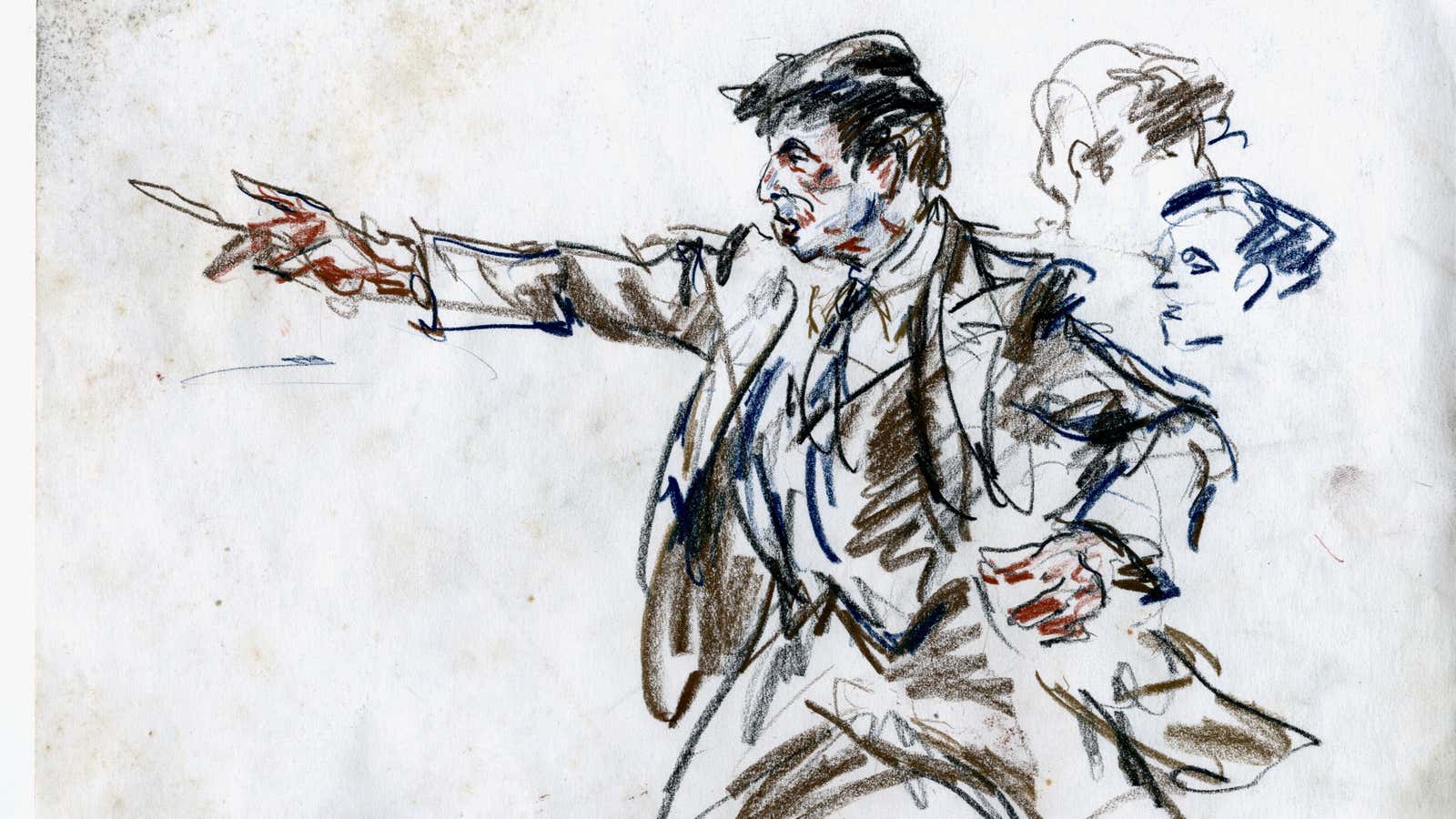

Watching established court artists work quickly transformed him from a snob to a fan. Lien came to appreciate the rigors of the job. “A sketch artist has none of the luxuries of a painter in a studio,” he explains. They can’t wait for the muse and are limited in the subjects they choose. And the conditions in the courtroom can be brutal.

Artists are crammed in small spaces drawing live action. No one poses for them, which means that Lien spends hearings trying to catch the most visually significant moments and capture them on paper.

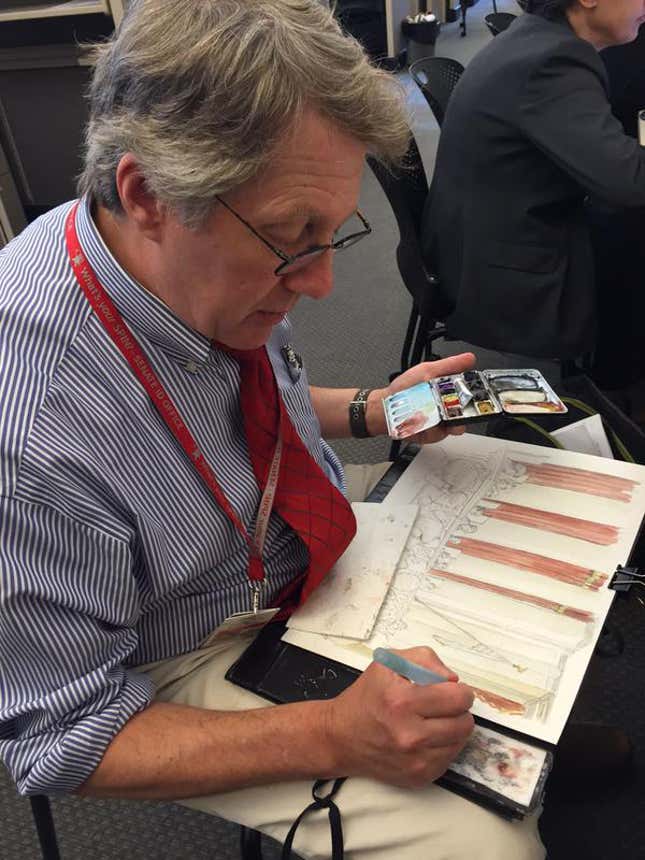

After many years of experimentation, Lien has finally found the perfect materials for the job. He uses a pencil and paper inside the courtroom; watercolors are painted at a desk in the press room after proceedings, with a special brush that holds fluid in the handle. Then, he scans the images and sends the work to editors.

Sadly, however, some sketches don’t get published. Lien recalls a high-profile story that was the lead NBC news report but didn’t include a single one of his many sketches. Cameras have already made courtroom art seem passé and editors can be disdainful. “I gripe about it with other artists,” Lien jokes.

Resistance is futile

Lien doesn’t oppose cameras in courts but notes that they aren’t as honest as people believe.

Cameras, he contends, are more deceptive than an artist. People accept something that is filmed as real—a true and objective record—so they fail to recognize the ways in which cameras, like humans, offer a subjective view.

But a sketch never pretends to be anything other than a perspective, a story told by an artist. In that sense then, the sketch artist’s work is more honest than the camera’s record, Lien argues.

Like a writer, Lien is making editorial judgments when drawing. He’s composing an image. So, he not only goes where the camera cannot, but also shows it. Lien’s images play with time and space to convey a sense of the subject. “You have to compress stuff,” he says.

And that compression can make even a single sketch more informative than an hour of filmed record. By emphasizing and curating information—the startling difference in height between an attorney and a client, say, or whatever distinctive collar Ruth Bader Ginsburg is wearing—the artist points a viewer to a noteworthy thing, or to a historical moment in the courtroom.

The electronic record

Fix the Court, a nonpartisan organization advocating for transparency in the federal judiciary, supports cameras in courtrooms. Executive director Gabe Roth tells Quartz that the public would have more faith in judges if they saw the judiciary at work. This is particularly the case with the Supreme Court justices, he says.

Like chief justice Roberts and Lien, Roth believes Americans would be impressed. “The public would see that there is still one branch of government that’s working more or less and is using its time in the spotlight to parse challenging legal questions, not to denigrate the other side or promote themselves for higher office, as officials in the other two branches are wont to do when cameras turn on.”

Sunny Hostin, a former federal prosecutor, and currently co-host of The View, also advocates for cameras. She testified before the House Judiciary Committee (pdf) that “there exists no better cure for fundamental mistrust and perceived illegitimacy of the judicial system than transparency.”

Hostin clerked for a Maryland state judge whose proceedings were filmed. She said none of the “parade of horribles” that opponents worry about—including hamming it up for the camera—came to pass. What happened is what the framers of the US Constitution wanted, Hostin argued. “The right of the public to attend trials is critical…and it has been upheld by the US Supreme Court. This is consistent with the Founders’ view of the Third Branch, a judiciary whose only power is judgment, the effect of which depends on the trust and confidence of the citizens it serves,” she testified.

The cost to taxpayers would be minimal, Roth adds, because public television could support the streaming. Yet the educational value of such a record “would be immeasurable.”

But the chief justice of the Supreme Court has already addressed this contention. If judgment is somehow affected by cameras, then Roberts thinks transparency isn’t worth it.

Lien believes that so long as even a single justice objects, there will be no change. The justices aren’t accustomed to disruptions. The artist recalls a dozen years during William Rehnquist’s time as chief when no jurists changed seats on the bench, arranged as they are according to seniority. Still, he’s sure cameras are in the court’s future and that the artist’s record he and his kind provide will disappear entirely.

He doesn’t believe court artists will be missed by many. But over more than four decades of sketching historical moments in American law, Lien has overcome his initial reservations about not creating “high art.”

The beauty of courtroom sketching is precisely that it’s unpretentious. Lien is anonymous and, unlike a camera, unobtrusive. “I draw on small paper,” he says happily.