Climate-driven disasters are reshaping our world. This week, we’ve seen a preview of what’s coming.

In California, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) cut off power to 500,000 homes in 20 counties (with more to come). More than 2 million people could ultimately be left in the dark. PG&E is testing a new strategy to avoid last year’s killer wildfires, which left 1.8 million acres scorched and more than 100 dead, after its errant power lines touched off massive infernos, the worst toll in state history.

Now, the utility is shutting off the power.

PG&E, accused of neglecting its infrastructure and the flammable vegetation near its power lines, faces forests left tinder-dry by a series of brutal droughts in the past decade. As the climate dries out the West, wildfires are burning hotter, longer, and bigger than before. Overwhelmed, the utility has decided its only strategy is to stop delivery of its essential service to millions.

So far, the urban core of Silicon Valley and San Francisco hasn’t been severely affected (the high-voltage power lines serving tech’s corporate campuses aren’t as likely to start fires), but many areas where the tech elite live—such as Marin, Napa, Sonoma, Santa Clara, and Contra Costa counties—are in the dark.

This week’s move may avoid a fire (and another bankruptcy), but it endangers a huge number of people who will need power to stay cool, preserve medications, refrigerate food, charge phones, or access gas pumps or ATMs, says Irwin Redlener, the director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. “If your remedy is cutting off power…you do that at a cost,” he says. “You’re [creating] a significant risk for a large number of people.”

We’re entering a climate era when there are no total solutions. There are only tradeoffs. Disaster relief is becoming less about rebuilding or fixing infrastructure, and more a way to buy time or retreat from the hardest-hit areas. In low-lying and fire-prone areas, communities are already beginning to abandon their homes, from Alaska to Louisiana. As the cost of defense and rebuilding after climate-driven disasters becomes too costly, exceeding the ability of even insurers and governments to absorb, this will become the new normal. Just defending coastal cities against storm surge with seawalls will cost at least $42 billion by 2040, according to environmental group the Center for Climate Integrity, and as much as $400 billion if including communities with less than 25,000 people.

Poor cities are the most vulnerable to climate change and the least prepared to counter it, according to a climate-impact study of the largest 100 US cities. But the climate crisis won’t spare the wealthy, either, says Redlener. “People with limited means are always going to do worse in initial impacts and also have a much more difficult time in the aftermath,” he notes. “But these [impacts] are essentially inevitable and affect the multimillionaires on Fisher Island [Florida’s richest zip code] and the poor people in Little Havana. There will be some equalization of impact.”

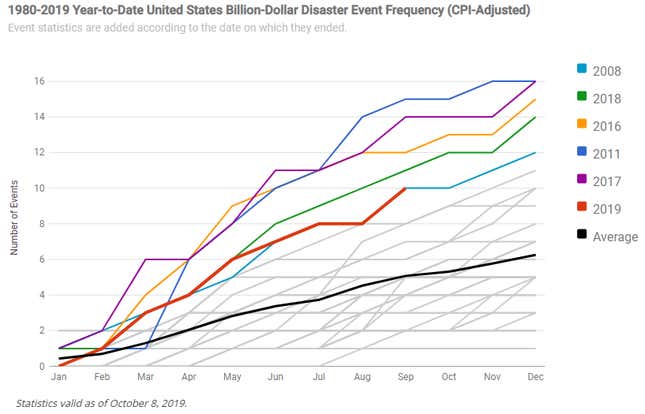

Since 1980, US weather-related disasters have incurred $1.7 trillion in damages. Every year, the average cost has grown. At least 10 weather and climate disaster events costing a billion dollars (or more) have hit the US for five consecutive years, an unprecedented amount. Over this time, the frequency of severe events has nearly tripled, with 3.75 severe events per year on average through the 1980s and 1990s, and rising to 11.6 events annually over the last five years.

California is on the front lines. While some people with means will buy batteries and solar panels to endure power outages, or expand the defensive perimeter against fire for their luxury homes, those measures will not stave off what is eventually coming. That story will be repeated across the hardest-hit areas in the West, South Florida, Texas, the mid-Atlantic, New Orleans, or the Mississippi River Valley.