The world’s biggest television event so far this year isn’t America’s Super Bowl, but a live, almost five-hour spectacular of song, dance, and skits hosted by China’s state television network. The annual Spring Festival Gala, which took place this past weekend as Chinese families celebrated the Lunar New Year, brings in as many as in 6.9 times more viewers than the US football game, or about 750 million people (paywall) as of last year.

This year’s ratings aren’t in yet, but there are signs that Chinese TV viewers weren’t as impressed as they have been in years past, when up to 60% of households tuned in to the Spring Festival Gala, also known as chun wan. There was a time when phrases and jokes uttered on the show become catchphrases for years. But chun wan, which has always been important culturally and commercially to China, is quickly losing relevance on both fronts.

According to one one survey (link in Chinese) almost 60 percent of the viewers polled said they were extremely disappointed. In past shows, comedians would riff on current social issues from food safety to pollution. This time, the comedic acts were shortened and sterilized. Jackie Chan mistakenly described a dance titled the “best night” as the “last night.” Bloggers questioned the artistic value of a 15-year-old girl spinning in circles for four hours. Other internet users mocked a singer intended to be running toward his “Chinese dream” as making no progress at all, given that he was on a treadmill.

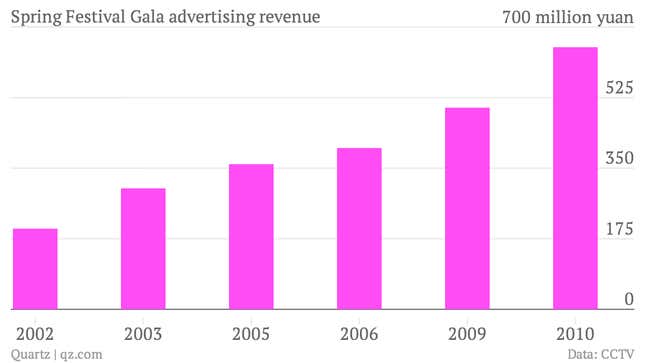

Moreover, in contrast to the Super Bowl, where an ad spot costs $4 million per 30 seconds, China has banned commercials for the past four years so that the program can focus more on promoting socialist ideals and celebrating China’s progress. Before the ban, advertising revenue for chun wan had been growing steadily (pdf, p. 36), reaching a record 650 million yuan (about $107 million) in 2010.

Companies can still benefit from the TV event. Tencent’s WeChat saw over 10 million messages sent during the course of the show as viewers discussed it with their friends, and Chinese handset maker Xiaomi spent 30 million yuan to air a commercial one minute before the program began. The commercial ban, however, does represent a shift in the program’s focus.

While the gala has always served an ideological purpose, it’s becoming even more of a propaganda tool—a trend that is losing the favor of Chinese viewers who are growing more impatient with boring, heavily scripted programs. Popular Chinese public figures like the singer Cui Jian and tennis star Li Na opted out of this year’s show. Even an editorial in the People’s Daily in 2012, China’s state-owned newspaper, called it a “passé gala.”