On Oct. 18, the US Supreme Court agreed to review a case about the constitutionality of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s leadership structure, the outcome of which threatens to unravel nearly a decade of work by the federal watchdog created in 2010. And, strangely, the agency—under director Kathy Kraninger, picked by Donald Trump and barely confirmed by the Senate in December 2018—is now arguing against itself.

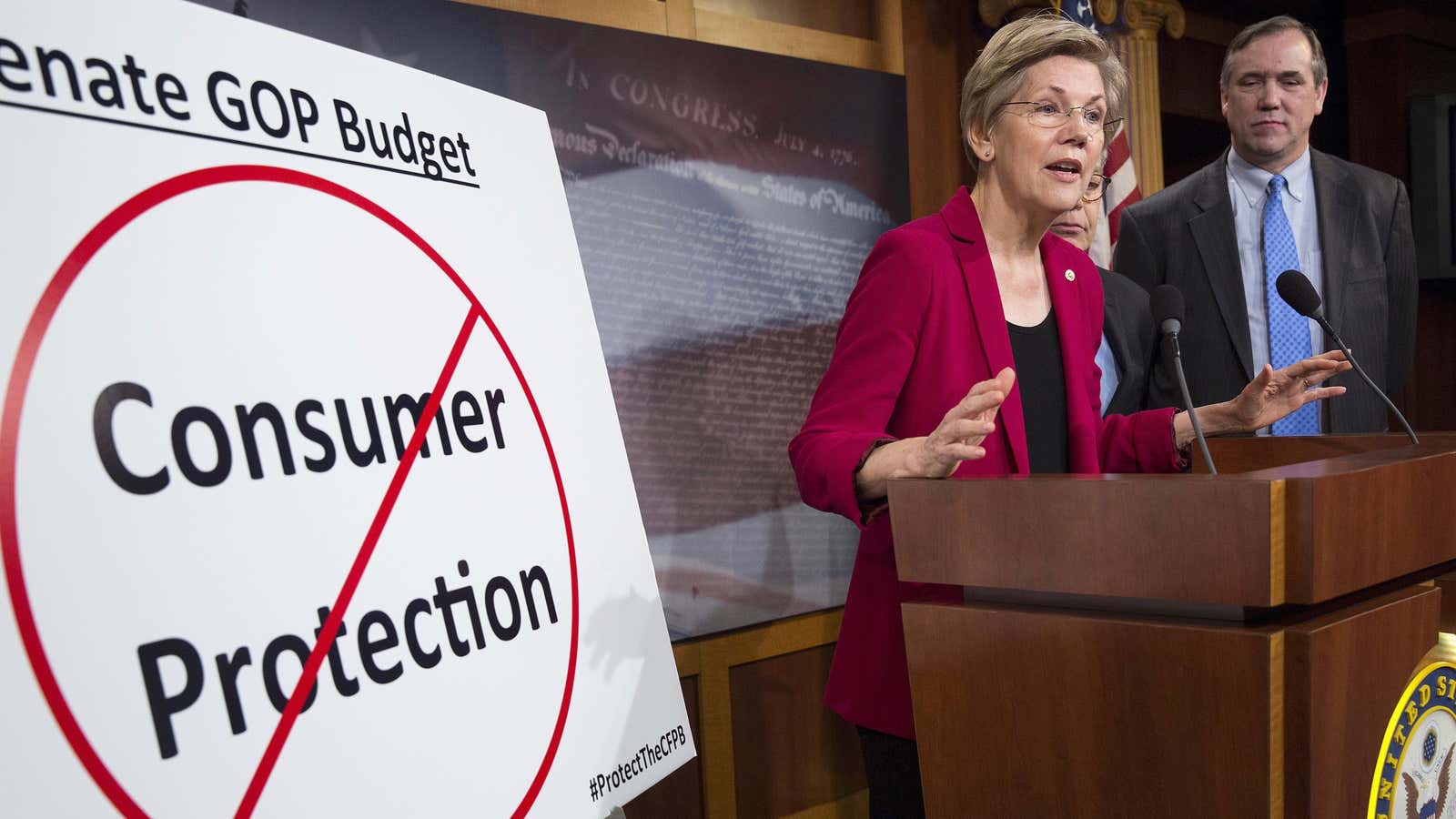

The CFPB, which has shut down numerous lending scams, was created in response to the 2008 financial meltdown and is in part the brainchild of Democratic presidential candidate and Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren. It’s meant to ensure that banks, lenders, and financial-services providers treat consumers fairly, according to its mission statement, and is part of the reorganized financial oversight scheme created by the 2010 Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

Republicans and banking executives are no fans of the agency. The Trump administration, which is a staunch advocate of executive power, argues that the bureau’s leadership structure is unconstitutional because its chief is a sole director with significant power in a five-year position and can only be removed by the president “for cause.” It argues that this violates the requirement of “separation of powers” in the Constitution. It also contends that the president, based on the language in the founding document, should be able to remove any of his officers for whatever reason or none at all, and not just for cause.

The bureau itself has successfully contended in the past that this requirement for the director ensures its independence from political pressures. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, while not indifferent to the challengers’ constitutional arguments, held that the CFPB didn’t prevent the president from faithfully executing the laws as is his constitutional duty and so wasn’t problematic.

Seila Law, a firm involved in consumer-debt cases that was under investigation by the CFPB, challenged the agency’s leadership structure after officials requested company documents. It turned to the high court for relief, seeking review. Now, the Department of Justice and the CFPB itself are in agreement with the law firm, and they in recent briefs to the high court also asked that the justices take the case.

That leaves the House of Representatives alone defending the decision to give the CFPB director so much power. “This case presents an issue of significant importance to the House: the constitutionality of the for-cause removal protection that Congress enacted to provide the CFPB director with a measure of independence, consistent with the agency’s functions as a financial regulator,” the House’s general counsel, Douglas Letter, argues in an amicus brief (pdf).

The justices responded affirmatively to the request for review, but asked the parties to be prepared to answer an additional, very important question: If the court agrees that the provision limiting the president’s ability to remove the CFPB director is unconstitutional, can that clause be separated from the rest of the Dodd-Frank Act? Or, in other words, would the work of the CFPB over the past nine years since its creation all be jeopardized by a finding that the director’s role as created violates separation of powers?

The bureau argues that the consequences of the case need not be so dramatic and that a decision about the director doesn’t have to unravel the CFPB’s decisions and actions. But it’s the justices who will ultimately decide whether the CFPB director’s role is unconstitutional and, if so, what that means for consumers in the grand scheme.

There’s already some indication of what at least one justice thinks. Brett Kavanaugh, while a judge on the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, in one case dissented from his colleagues’ decision to reject challenges to the CFPB’s leadership, calling the bureau director’s power “massive in scope” and “unaccountable to the president.”