Before there was antitrust, there were trusts.

A “trust” is a group of firms or industries organized to concentrate power, and reduce or eliminate competition. The model developed in the 1880s, as burgeoning oil baron John D. Rockefeller sought to consolidate his holdings across state borders by placing stock from different properties into a single entity known as a trust. As Open Markets Institute fellow Matt Stoller explains in his new book, Goliath:

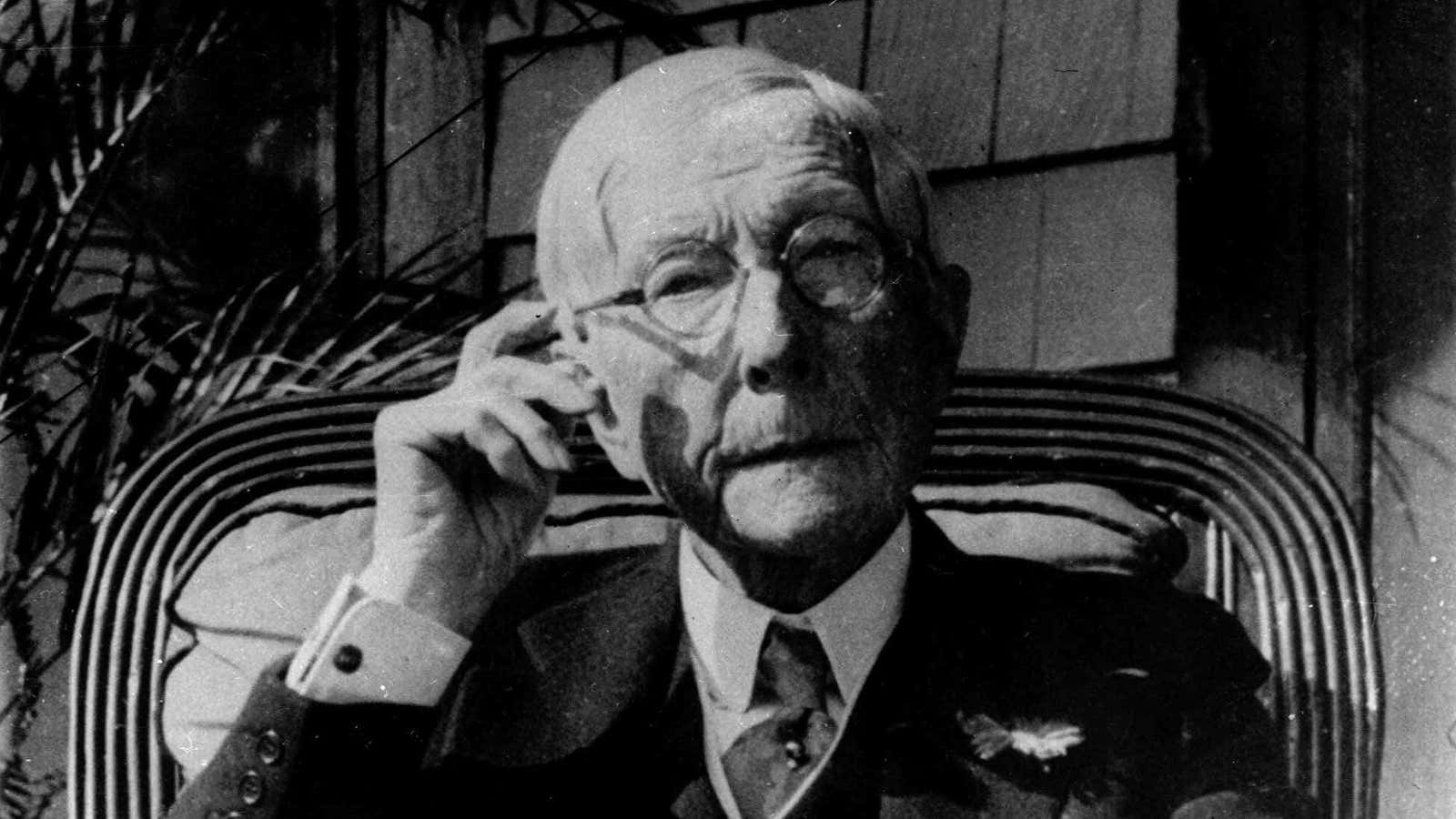

Until the 1880s, vast new industrial power was regulated at a state level through restrictive corporate chartering. For instance, state corporate charters did not allow one corporation to buy stock in another. But in 1882, an oil refiner named John D. Rockefeller helped invent a centralizing legal tool to capture industries across state borders. He placed all stock from various oil properties into one legal structure called a “trust.” Known as the Standard Oil Trust, Rockefeller’s oil companies might look independent legally, but the trust’s board of directors set policy for the combined group. With this new legal tool, Rockefeller built the largest and most powerful monopoly of the era.

Standard Oil is often referred to as the first trust, and the legal mechanism Rockefeller pioneered paved the way for an unprecedented period of monopolization in the US. It marked the birth of the giant corporations that today dominate the daily lives of people around the world. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil consolidated the oil industry; financier John Pierpont Morgan organized General Electric and US Steel, and captured the railroads. Rich Uncle Pennybags, the round-faced, mustachioed mascot created in 1936 for the Monopoly board game, was modeled on Morgan.

This is part of our field guide on Taming Big Tech, available exclusively to members. If you haven’t already, sign up here for a free trial.

It only took about 20 years for these Gilded Age tycoons to seize control of the US economy. Morgan and his peers capitalized on the unregulated, “ruinous” competition that fueled speculative investments and race-to-the-bottom pricing that culminated in wage cuts, violent strikes, and economic collapse. They viewed the concentrated power of trusts as a superior economic model.

Morgan took control of bankrupt firms and their competitors to settle price wars. He overhauled management teams and restructured debt, tactics that became known as Morganization. Rockefeller described the growth of large business as “a survival of the fittest… the working out of a law of nature, and a law of God,” according to Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness.

Antitrust, as the word suggests, emerged as a direct reaction to this trend. In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act, the foundation of US antitrust law, in response to the sprawling reach of trusts like Standard Oil. The Sherman Act barred “monopolization” and “restraints of trade.” John Sherman, the US senator from Ohio whom the law is named for, declared monopolies “inconsistent with our form of government.”

“If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessaries of life,” he famously told Congress. “If we would not submit to an emperor, we should not submit to an autocrat of trade.”