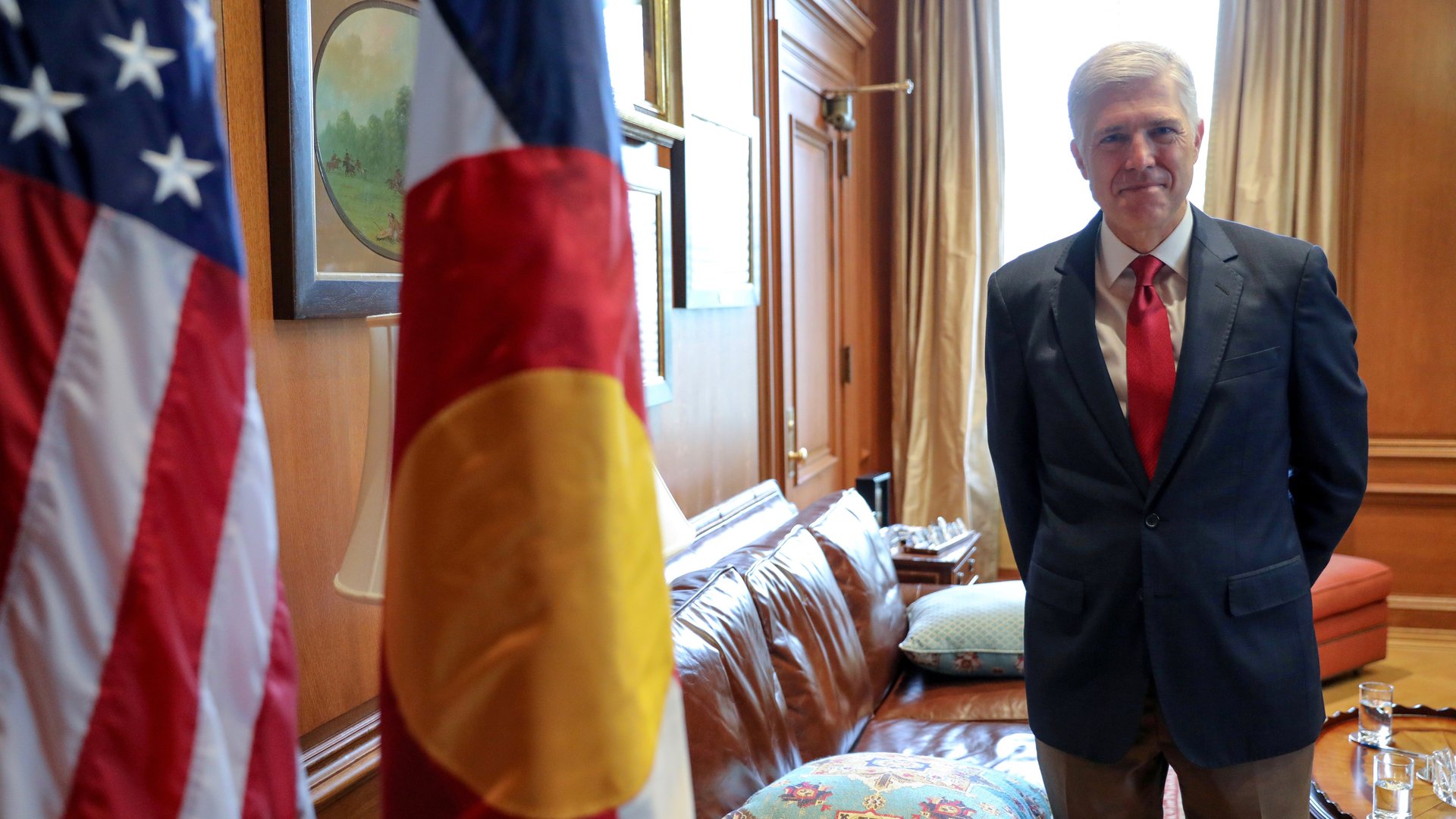

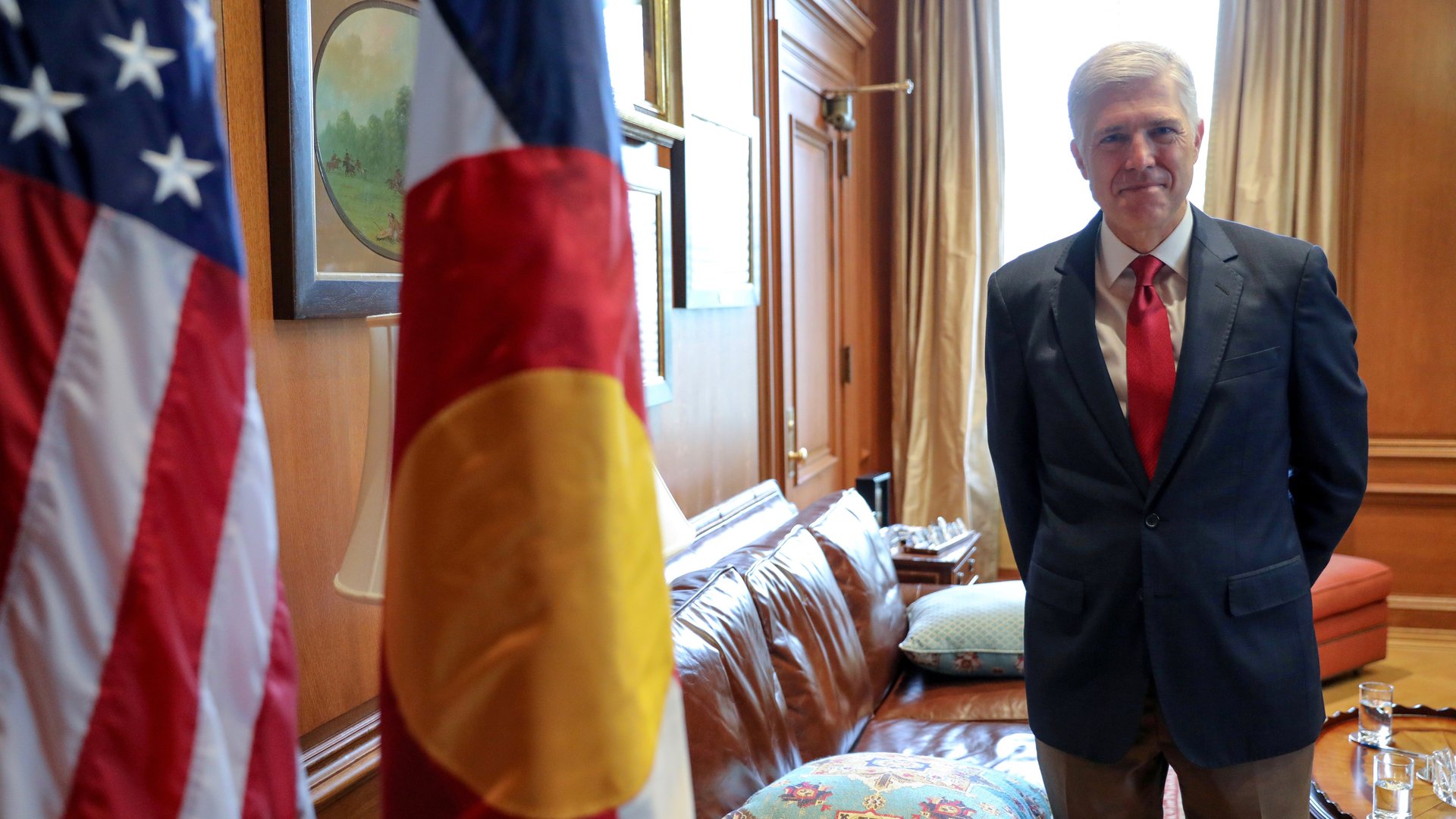

US Supreme Court justice Neil Gorsuch apparently has a sense of humor

US Supreme Court justice Neil Gorsuch can get grumpy on the bench. If a lawyer’s answers annoy him, he’s curt. Yet today (Nov. 4), at arguments in a case about cops, traffic stops, and the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution, Gorsuch was amused and amusing.

US Supreme Court justice Neil Gorsuch can get grumpy on the bench. If a lawyer’s answers annoy him, he’s curt. Yet today (Nov. 4), at arguments in a case about cops, traffic stops, and the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution, Gorsuch was amused and amusing.

The matter stems from a traffic stop in Kansas, where a sheriff’s deputy ran a registration check on a truck and discovered the owner, Charles Glover, had a revoked license. Based on the assumption that Glover was the driver of the vehicle registered in his name, the officer stopped and arrested him for driving without a valid license.

Glover has managed to suppress the arrest on the grounds that the officer’s assumption violates the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable governmental searches and seizures. An investigatory stop is permitted when an officer has a reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing based on articulable facts. Glover argues, and the Kansas Supreme Court agreed, that the officer’s inference that a car is likely being driven by its registered owner—when that owner doesn’t have a valid license to boot—doesn’t rise to that level.

The cop offered no other facts besides this assumption. He didn’t testify at the hearing on the motion to suppress and the Kansas court concluded he shirked his constitutional duty to articulate the facts underlying his suspicion.

Kansas, supported by the federal government, argues that it’s a common sense presumption, and has put the question before the high court. Now, the justices must decide, and—based on arguments today—it seems that Gorsuch is extremely intrigued, but torn.

He asked the hearing’s first question, challenging Kansas’s solicitor general. “You’re asking us to make an inference about facts when there are no facts in the record at all, zero… other than an assumption,” Gorsuch complained.

The justice pointed out that in cases where the inference was made and found constitutional, officers provided other facts for a judge to conclude that the stop was reasonable. “Here, we don’t have any facts from the officer about experience or realities on the ground. And yet you’re asking the judge to make a legal conclusion about certain facts on the ground that are not present in the record.”

Gorsuch, evidently feeling feisty, marveled at Kansas’s position, saying, “It’s almost like a judicial notice of facts not in record.” Counsel began to reply, but the justice cut him off, laughing sarcastically and asking, “Is that a thing?”

Built-in obsolescence

Gorsuch also pointed out that making a bright-line rule that it is reasonable for an officer to assume the driver of a vehicle registered to an owner is at the steering wheel might be of limited utility. Even if the assumption was sensible today, it won’t hold up in the future, he posited.

Gorsuch challenged the logic of the state and federal governments’ arguments. He said they relied too heavily on dated presumptions, explaining his doubts while revealing his feel for the zeitgeist:

It seems to me that a lot hinges on … [a] common sense assumption that the drivers of vehicles typically are the owners of the vehicle… And that might be true in our contemporary contingent historical reality, but the next generation, for example, often rents cars. They don’t buy cars. They don’t own cars. You’re asking us to write a rule for the Constitution that presumably has some duration to it. Is this one with a short expiration date?

Counsel muttered something about cars and the Airbnb of the future. However, Gorsuch’s opposition seemed unconquerable. That is, until he turned his attention to Glover’s attorney.

Tough cop

It turned out Gorsuch wasn’t entirely sold on Glover’s claim. He asked what facts would have been enough for the officer’s suspicion to be reasonable and wondered if a set of “magic words” or a “talismanic” formulation would make any difference.

The justice asked, “If all that is at issue here is that Kansas forgot, neglected, to put an officer on the stand to say ‘in my experience’ the driver is usually the owner of the car or often is, what are we fighting about here?”

Shortly thereafter, Gorsuch decided to actually play the role of this imaginary officer at a motion to suppress a hearing in a courtroom describing a traffic stop. And in his mind, the cop was a tough guy, apparently, so he hunched forward and adopted a hard-boiled-detective-on-tv type tone. “I’m an officer. This is what I do… I assume this is the driver, okay?”

The performance by the justice from Colorado fell flat with Glover’s midwestern attorney. “This is Kansas, not New York,” counsel corrected Gorsuch, reminding him where his imaginary scene would really be taking place.

Undeterred, he briefly continued with his accent before conceding her point over laughter in the courtroom. “Touché,” Gorsuch replied.