Supreme Court justice Neil Gorsuch’s new book, A Republic, If You Can Keep It, is a true believer’s tale of faith in the US constitution, written for the politically jaded. In it, Gorsuch is a high priest of the law, aiming to convert disillusioned citizens into coreligionists.

The book was mocked by McSweeney’s as a misguidedly nostalgic call for a return to more “civilized” times when women didn’t vote and the esteemed founding fathers had slaves. But contrary to complaints, the text actually reveals that Gorsuch at least wants to be seen as everyone’s justice, servant of the people, not any political party.

The justice from Colorado, who came from the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, is relatively new to the high court. His appointment in 2017 wasn’t exactly met with enthusiasm by Democrats, who predicted that his decisions would advance Republican party goals. But so far Gorsuch has shown that his opinions aren’t quite as predictable as expected. He insists in his book that the law and facts dictate each outcome, not personal politics, and there’s some evidence in his Supreme Court record to support his claim that judges are not politicians.

It’s typical stuff for a Supreme Court justice, conservative or liberal, the standard rhetoric of the American judiciary. Sure, Gorsuch is an aristocrat, a proud son of the west who picked up a British doctorate and a wife at Oxford before ascending to the highest court in the land. But he emphasizes that the US is a nation of equals before the law and of immigrants participating in a diverse project that relies on all, and he hardly seems unaware of the stains on its history.

Gorsuch doesn’t seem to be saying that the good old days were great, but that the ideals expressed by the founders require people to aspire to everyday greatness, which manifests in big and small ways. For example, in a section on the responsibilities that come with the freedom of speech granted by the First Amendment that reads like a personal plea, he writes, “That means tolerating those who don’t agree with us, or whose ideas upset us; giving others benefit of the doubt about their motives; listening and engaging with the merits of their ideas rather than dismissing them because of our own preconceptions about the speaker and topic.”

These themes have been emphasized by his colleagues before him, most notably by John Roberts and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, as well as by former justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Like them, Gorsuch apparently relishes politesse. His writing suggests that little kindnesses are the glue binding civilization and he waxes poetic about court collegiality, the many handshakes justices exchange on argument days, shared meals, the annual skit night when clerks poke fun at their bosses’ foibles, flipping burgers at court picnics, all proof that the bench keeps it friendly even when disagreeing on important legal issues, and that these gestures are what enable debate.

With this book, Gorsuch says, he wants to share his understanding of the uniquely apolitical role of judges in government. Though appointed in a political process, the subtext of this text seems to be convincing Americans that Gorsuch isn’t US president Donald Trump’s puppet or an arm of the Conservative party, even if he is very much a conservative judge.

Big C, little c

The justice distinguishes between interpreting the law conservatively, with a small c, which he does, and political Conservatives, with a capital C, who actively support the Republican party. He is a conservative jurist because he’s restrained, he claims.

Gorsuch believes judges interpret law, not make it. Outcomes are dictated by rules about how to read legal language rather than his own notions of progress or purpose or politics.

During his high court confirmation process in 2017, however, Gorsuch says he was shocked to discover that many Americans see judges as politicians who should help or halt certain causes and policies rather than weigh the words of the law and the facts of a case and decide according to judicial dictates. He writes:

I heard people talking about the law and my decades in the profession in ways I didn’t recognize. Some suggested that as a judge, I “liked” one group of people or “disliked” another. In an effort to prove their point, they would sometimes single out a case where I had ruled for or against a particular kind of person but overlook plenty of cases where I had ruled the other way. Often too, they would fail to engage with the critical legal or factual reasons for the different outcomes.

These failures in the media lead to a widespread misunderstanding about how cases are really decided, Gorsuch says. He contends that “Lady Justice is blind for a reason.” In his view, a judge’s job is to interpret the law according to certain guidelines and follow the outcomes where they may lead. In this 300-page treatise on his chosen blinders—originalism and textualism—the justice explains the principles behind his decision-making.

Guided by grammar

Gorsuch explains how originalism and textualism work by saying, “Rather than guess about unspoken purposes hidden in the hearts of legislators or rework the law to meet the judge’s estimation of what an ‘evolving’ or ‘maturing’ society should look like, an originalist and textualist will study dictionary definitions, rules of grammar, and the historical context, all to determine what the law meant to the people when their representatives adopted it.” These principles, he claims, safeguard citizens from a judge’s personal ambitions for society.

The holdings people use to assess Gorsuch’s politics and person aren’t based on outcomes he preferred necessarily, he argues, but on the dictates of the law as read through an originalist and textualist lens. Sometimes, it means he sides with a murderer’s right to use a sweat lodge while in prison, although the prisoner is an unpopular party, and at other times it means Gorsuch sides with a business objecting to nationally mandated insurance coverage for religious reasons.

It’s notable that the justice doesn’t name one of his most controversial decisions while on the 10th circuit, the 2013 case Hobby Lobby v. Sibelius (pdf), where he found, along with a majority of 10th circuit judges, for the Christian owners of the crafts chain store Hobby Lobby, which denied women insurance coverage for procedures that contravened the owners’ faith. But he does appear to allude to it as proof that a textualist’s path will sometimes lead to unpopular decisions.

Gorsuch claims that by letting legal reading rules govern outcomes, rather than beliefs, he’s coming as close to justice as is possible, taking his feelings out of the equation. That is fairness, he says. And while not everyone would agree it’s even possible for a judge to make an unbiased decision, to the extent that there’s truth to his claim, it must be noted that Gorsuch did, in the last Supreme Court term, prove an unexpected ally of liberal justices, ruling with the court’s four left-leaning jurists in four close cases, giving them a majority more often than any of his other conservative colleagues.

A snoot, but no DFW

Gorsuch says his book is for a lay audience, and not legal scholars. But do not expect a thriller. As a literary endeavor, it’s a bit lazy.

The text is mostly a compilation of speeches, texts, articles, decisions, and letters that Gorsuch has written about the law and judicial philosophy over the years, with a smattering of more recent personal chatter. It lacks a narrative and seems collaged—part plea, part legal anthology, part place holder for the next tome.

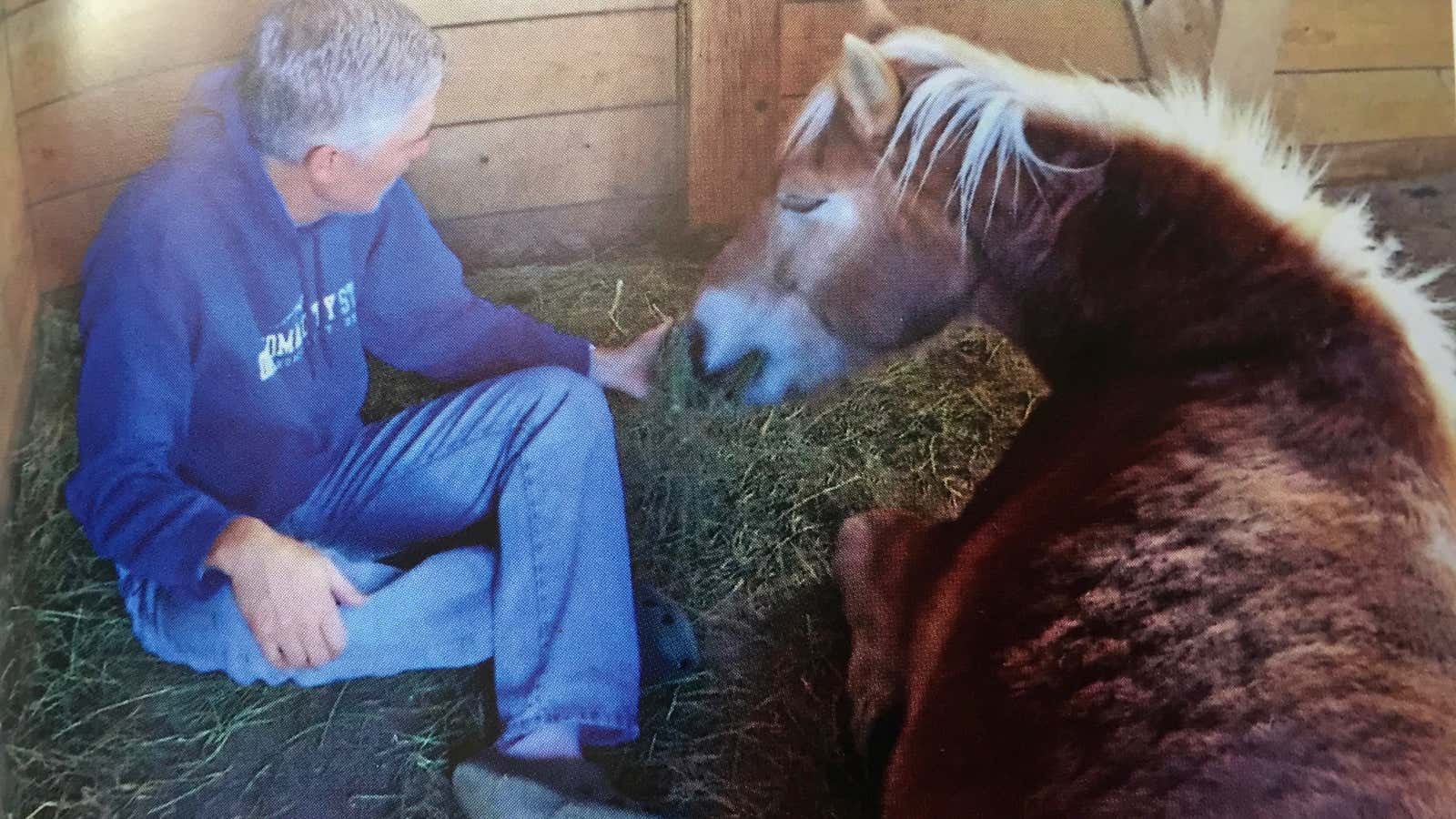

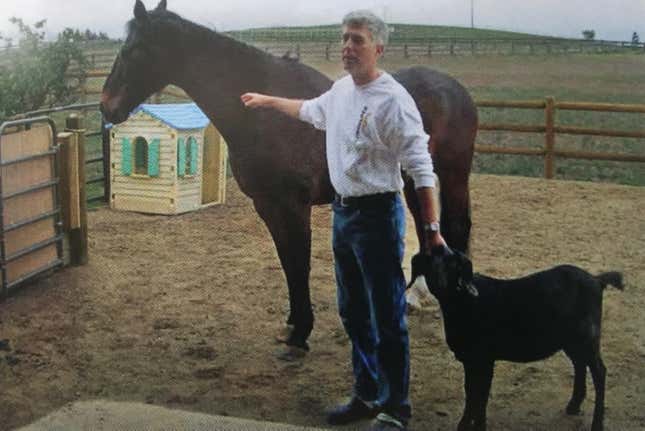

But there are charming photos of the justice as a boy fishing with his father, and later doing the same with his young daughters, as well as images of Gorsuch in what appears to be Birkenstock clogs, or possibly Crocs, hanging out in his barn with a horse, and chilling with baby chicks in his office.

And, ironically enough, the justice asks not to be judged just yet, acknowledging that he’s new to the job of supreme jurist and promising more to come.

Gorsuch can be a funny writer and he obviously admires literature. He references David Foster Wallace, author of the wildly imaginative novel Infinite Jest, a few times. And it’s true Gorsuch is a SNOOT, which was Wallace’s coinage for word nerds, or “Syntax Nudniks of Our Time.”

But Gorsuch is as stylistically restrained as DFW was loose. The good news is that it doesn’t read as jest.

Correction: An earlier version of this post referred to Wallace as the writer of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. That is Dave Eggers.