Senators Jacky Rosen and James Lankford, who describe themselves as “a practicing Jewish Democrat from Nevada and a devoted Christian Republican from Oklahoma,” are spearheading a new effort to fight an old problem: antisemitism in America.

The Bipartisan Task Force for Combating Anti-Semitism, wrote the senators in an opinion column for CNN, will “collaborate with law enforcement, federal agencies, state and local government, educators, advocates, clergy, and other stakeholders to combat antisemitism by educating and empowering our communities.”

They’ve got a big job ahead of them.

Ancient roots

In early September, Trenton’s City Council President Kathy McBride uttered the phrase “Jew her down” in a public discussion. McBride said she was sorry 12 days later. The Associated Press ran the headline: “Politician apologizes for use of anti-Semitic trope.”

Congresswoman Ilhan Omar responded to GOP threats to censure her for denouncing Israel, “It’s all about the Benjamins baby.” She was referring to the dollars AIPAC, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, purportedly throws at legislators standing up for Israel. Omar later apologized.

President Trump tells American Jews: “If you vote for a Democrat, you’re being very disloyal to Jewish people and you’re being very disloyal to Israel.”

Likely none of these politicians grasped in the moment the antisemitism underlying their remarks. This was not the first time on American soil that Jews were charged with financial cunning, government manipulation, and questionable loyalty.

These canards, rooted in ancient and medieval anti-Judaism, have a long history in America.

Religious antisemitism

There are different strains of antisemitism.

Religious antisemitism is the charge that the Jews were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus. In this formulation, their descendants must, forever, pay for that treachery—sometimes by being locked behind ghetto walls, other times with their lives. It dates to the split of Christianity from Judaism in the first century.

Fifteen centuries later, in 1654, New Amsterdam Governor Peter Stuyvesant tried to expel the 23 Jews fleeing persecution who had just landed in the colony. He called them a “deceitful race—such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ.”

Subsequently, American Sunday school primers, Bible mission tracts and popular novels recalled Jews’ complicity in the murder of Jesus and sought to convert them. Sabbath Lessons (1813) taught Sunday school children about the “conspiracy of the Jewish rulers against Jesus Christ.” In the novel The Prince of the House of David (1855), part of a trilogy which reportedly sold over 5 million copies, the author, an Episcopal priest, called on “the daughters of Israel” to abandon Judaism and follow Christ.

Mel Gibson’s 2004 film The Passion of the Christ carried religious antisemitism into the 21st century. Its Jewish mob—the men’s beards and noses immense, their heads covered in prayer shawls—appeared on the wide screen screaming “Crucify him” to a bloodied Jesus standing before the Roman Governor Pontius Pilate.

Money and power

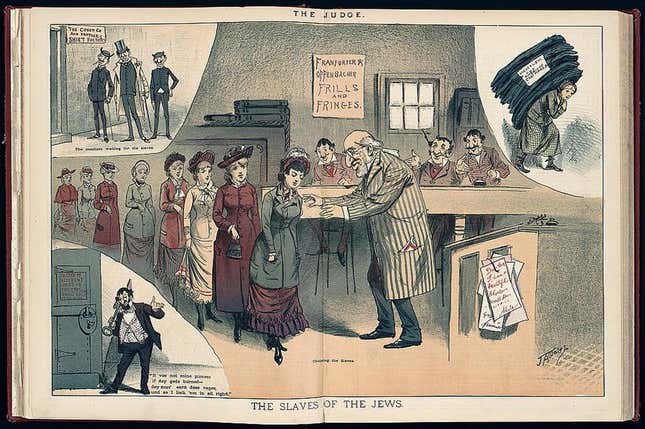

The antisemitism making headlines today doesn’t always replay the charge that the Jews killed Jesus. Instead it draws from a long roster of other anti-Jewish stereotypes. They depict the Jews as a people interested only in money, malevolently employing their wealth to undermine the political order.

In just six words, “about the Benjamins,” Minnesota’s Rep. Omar echoed age-old claims of Jewish cunning, financial manipulation, and government control. Her remarks echoed those of an 1852 New York Times journalist who wrote of Jews’ “sharp schooling in money-getting” and that, controlling all capital, they declared “empires solvent or bankrupt, at will.”

Later in the 19th century, in the January 1897 Atlantic Monthly a friend of Harvard professor and ambassador James Russell Lowell recalled how Lowell—a minister’s son who knew Hebrew—decried Jewish bankers, brokers, and the ones who had slipped into politics and diplomacy. Lowell feared that they were poised to control “the Earth’s surface.”

Lowell’s sentiment was typical of many of his generation’s well-bred, well-educated public servants, intellectuals, and civic leaders.

In 1890, the Reverend Charles F. Deems wrote of a segment of Jews whose only passion is “the greed of gain.” In novels, that love for money translated into the charge that Jews “control the money power of the world.”

Lowell’s assertion of an international Jewish conspiracy predated the forgery known as the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” It first appeared in Russia in 1905 in a book about the coming of the Antichrist published by the mystic Sergei Nilus. Its antisemitic fantasies of Jewish leaders plotting to destroy Christianity and control the world inspired Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

The myth of a world Jewish conspiracy found a home in America in the 1920s thanks to publication of The International Jew – The World’s Foremost Problem. Quoting liberally from the “Protocols,” this series in the Dearborn Independent newspaper was subsequently published as a multi-volume book.

The International Jew charged that the Jews controlled the world’s finances, that they were the “power behind many a throne.”

Circulation of the Dearborn Independent grew to 700,000 by 1924-1925 as its publisher mailed thousands of copies around the country, to bank presidents, Rotary clubs, women’s clubs, college presidents, and the members of Congress. The publisher was the industrial tycoon Henry Ford.

Forever outsiders

When Donald Trump said American Jews who opposed his policies were disloyal to the Jewish people and to Israel, he was saying that Jews held dual loyalty.

Forever outsiders and aliens, in this view, Jews put their devotion to the Jewish people above allegiance to their nation.

In 2015, NPR host Diane Rehm asked Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders whether his “dual citizenship” with Israel disqualified him to serve as US president. Senator Sanders is not a citizen of the State of Israel.

The dual-loyalty accusations have dogged Jews across time and across the globe. Napoleon put the question bluntly to an assembly of Jewish notables in 1806: “Do Jews born in France, and treated by the law as French citizens, consider France as their country? Are they bound to defend it? Are they bound to obey (its) laws?”

In 1890, observing a spike in antisemitism that saw Jews excluded from summer resorts, blackballed as members of private clubs, and denied admission to private schools, the editors of the New York Jewish newspaper the American Hebrew asked more than 50 clergy, college presidents, lawyers, and politicians about “Prejudices Against the Jews.” They then published the responses.

Tufts College President E.N. Capen declared: The Jews could never “assimilate like other aliens; they are always Hebrew … They never can be Americans, pure and simple.” His was not the only response to state starkly that the Jews remained a nation within a nation.

After the state of Israel was established in 1948, its Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion declared: “The Jews of the United States, as a community and as individuals, have only one political attachment and that is to the United States of America. They owe no political allegiance to Israel.”

In charging Jews who vote for the Democratic Party—as the majority of American Jews do—with disloyalty to their people and Israel, President Trump turns that principle on its head.

Once again an old charge is voiced. Jews can never be fully Americans. Their loyalty to the Jewish people and to Israel trumps their loyalty to America.

With antisemitism today bombarding American Jews from the right and the left, the moment appears new, but its language is not. It’s a very old theme.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.