The mass protest movement that has gripped Lebanon since the middle of October, and which had recently seen its turnout lag, is now benefitting from a key strategic shift: avoiding tactics that might alienate some members of the public.

Demonstrators, fed up with political corruption and economic inequality, are calling for a new and technocratic government. Their actions have so far led to the passage of a package of reforms aimed at reducing the economic divide—which many protesters saw as too little, too late—and the resignation of prime minister Saad Hariri.

Until this week most of the protest actions outside the main demonstrations in downtown Beirut and other cities across the country focused on shutting down roads. Lebanon Support, a nonprofit research group, mapped the collective actions of protesters around the country, and found that the majority of them relied on roadblocks.

There is a case for blocking traffic: Research shows that nonviolent behavior that disrupts everyday life, and which affects at least 3.5% of a country’s population, can potentially bring about change. But roadblocks can also annoy residents, driving them to support the government and police actions against protesters. The government likely knows this, and has promoted an anti-roadblock message that appears to be resonating.

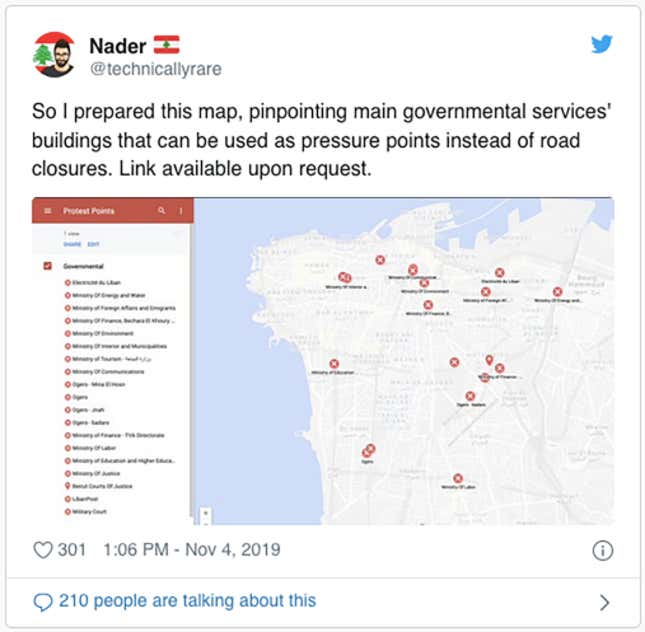

So activists have shifted strategy. They are now increasingly targeting specific government buildings and affiliated entities that they see as symbols and causes of the political and economic problems facing the country. Protest organizers have created maps to guide demonstrators toward these sites.

One of those key protest points has been the Justice Palace, which houses the country’s high court, where protesters have gathered to denounce alleged financial misdeeds. Already, the caretaker justice minister has cited protests as one reason for the ministry’s recent resolve to move forward on years-old corruption cases.

Protesters have also targeted the Electricité Du Liban, the state-owned power provider. Lebanon grapples with hours of daily power outages, and has the world’s fourth-worst power supply (pdf, p. 210), according to a report written by the McKinsey & Company consulting firm and released by the Lebanese government.

Demonstrators have also gathered outside the offices of Alfa and Touch, the country’s two mobile telecom providers. Mobile and data charges in Lebanon are some of the highest in the world. A now-rescinded $6-a-month tax on WhatsApp and other chat services that rely on internet data is what first ignited the unrest.

The ranks of protesters were likewise helped in recent days by striking high school and university students. Thousands have walked out of schools, and yesterday representatives from various universities met and agreed to unite their efforts. Crowds also gathered outside the Ministry of Education today to call for more affordable tuition and jobs.