Alzheimer’s, one of the direst health threats in the US, is not showing signs of slowing down.

The neurodegenerative disease that leads to brain cell degeneration and a decline in cognitive functions is estimated to kill a third of US seniors, which is more than breast cancer and prostate cancer combined. What’s more, while deaths related to heart disease—the nation’s leading killer —have been on a decline over the past several decades, Alzheimer’s-related fatalities have increased nearly 150%.

The lack of tangible progress for Alzheimer’s patients isn’t an issue of inattention. Despite the urgency of the situation, however, efforts to treat the disease, much less cure it, have produced few gains. Complex disease biology and the interplay of biology, drug mechanisms and aging may be a part of the reason

However, there’s another theory on why. For the most part, past efforts from researchers have focused on creating a drug that will effectively treat or cure Alzheimer’s when the disease has already manifested itself and progressed too far. Now researchers have started to appreciate that fighting Alzheimer’s requires a field-wide shift in our approach and thinking.

The real breakthrough may be unveiled when treatments are considered for people before the disease becomes visible on traditional clinical assessments performed by doctors. Changing how we interact with patients and detect traditional signs of the disease well before it takes hold may lead to early detection and create opportunities to develop new treatments or determine which drugs – perhaps even some that were previously shown to be ineffective – may become relevant if given to patients earlier.

Several of the world’s largest and most successful pharmaceutical companies have sought to tackle the disease. Unfortunately, nearly all of them have been met with insurmountable setbacks that ultimately led to discontinuing their clinical trials. This year alone Roche, AC Immune, Biogen, and, most recently, Amgen and Novartis have all halted their experimental Alzheimer’s treatments due to poor clinical trial data.

Notably, Biogen sent shock waves through the industry last month when it surfaced new data supporting its previously failed Alzheimer’s drug, aducanumab, and announced plans to seek its approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although preliminary, these findings are a critical step toward addressing the disease.

But progress has also come with a warning sign. The series of setbacks we’ve experienced just this year have dealt a devastating blow to patients, to their families and caretakers, and to the life science community as a whole. This highlights a very real problem, in which hope for a cure, and the disappointment of yet another trial failure, has in itself become a devastating reality in the Alzheimer’s community.

Rethinking the hypothesis

For decades, the prevailing theory behind the root cause of Alzheimer’s has been the amyloid hypothesis, which posits that the disease evolves from a build-up of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid in the brain. Researchers who subscribe to this theory believe that the disease ultimately stems from biological problems related to production, accumulation, or disposal of this protein.

Pharmaceutical companies worldwide latched on to the premise by creating experimental drugs that target removing amyloid buildup. The theory has produced upwards of 200 therapies, all of which—with the possible exception of Biogen’s—have failed.

The amyloid hypothesis has come under question as a result, and has even been outright abandoned by some researchers and leaders in the field.

This was clear at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) this year, where several thought leaders used their podium to call for researchers to look beyond beta-amyloid.

Although this year’s event left scientists with a lack of answers, it also exposed an important silver lining: The thus-far fruitless search for a cause is forcing us to look beyond the scope of the disease alone and is staring to bring the medical industry together in new ways. An environment of failure and dashed hope is requiring people to open their minds to new approaches, methods, and disciplines.

For instance, speakers at the AAIC drew attention to potential links between Alzheimer’s and infections, such as the herpes simplex virus, as well as the merits and detriments of exercise on disease progression.

Even with these unconventional links, the amyloid theory is still considered the most reliable tell-tale sign of Alzheimer’s.

But by the time a build-up of beta-amyloid is detected, it’s usually too late. Scientists are now beginning to view the presence of the protein as a “you’ve-gone-too-far” mile marker.

As a result, a groundswell of support is brewing to find signs of Alzheimer’s before amyloid plaques even materialize.

Biomarkers

In the midst of healthcare company Merck & Co’s failed Alzheimer’s study in 2017, David Knopman, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, made a striking statement: “Removing amyloid once people have established dementia is closing the barn door after the cows have left.”

Underpinning the hundreds of studies that have failed is the fact that we have been unable to see Alzheimer’s pre-symptomatically.

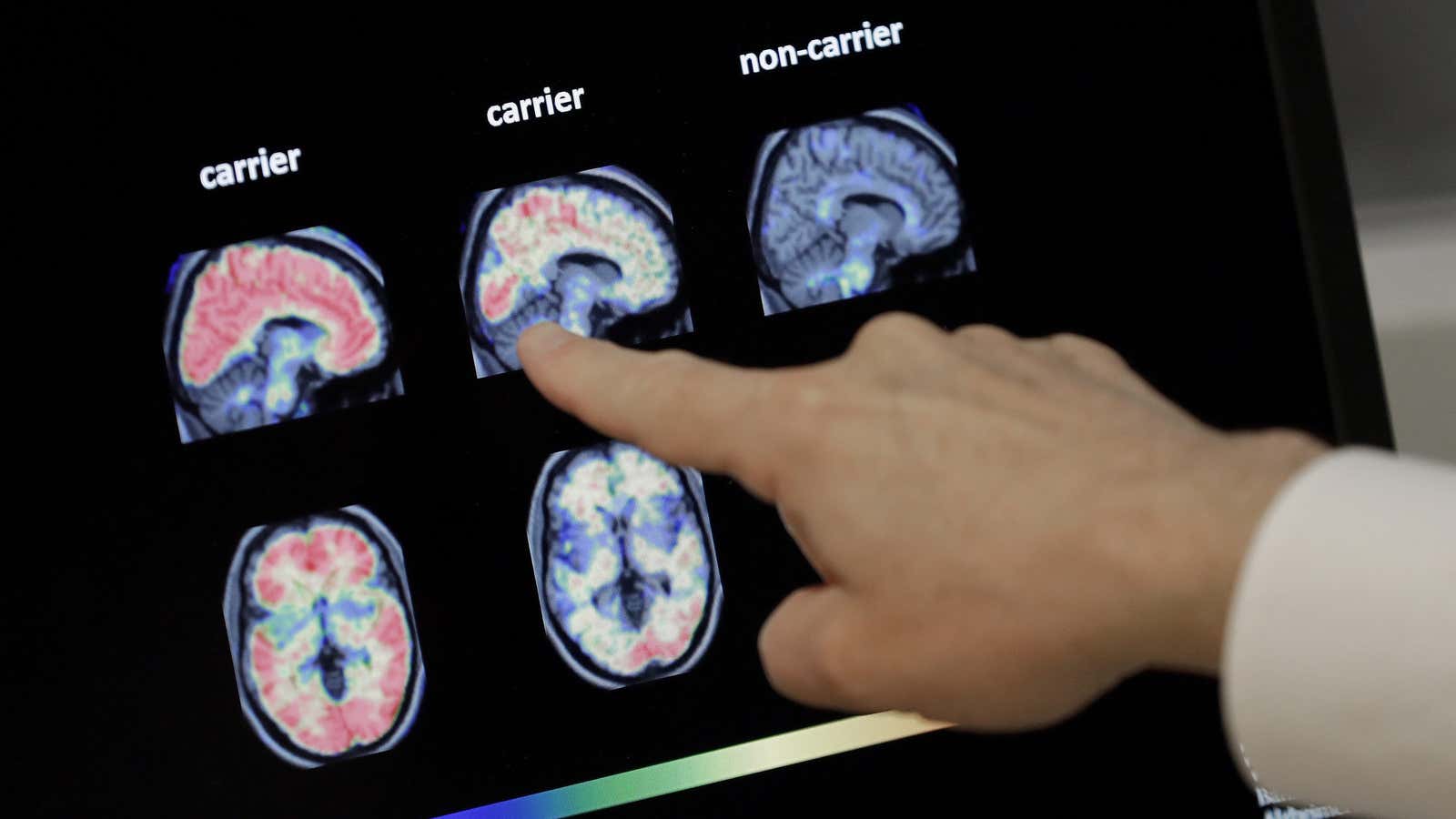

Up until recently, an Alzheimer’s diagnosis has been largely based on behavioral changes and other subjective observations. The prevailing output has been identifying and treating Alzheimer’s patients far too late in the disease cascade. By the time we see symptoms, the disease has not only fully taken hold, but it has likely already caused irreversible neurological damage.

What if we could identify future Alzheimer’s patients at stage zero and point treatments at staving off the disease entirely?

As news of failed drug trials made headline after headline, we have begun to witness a ripple awareness of a new way to detect Alzheimer’s years before symptoms, and potentially track how effective treatments are at halting or reversing the disease: biomarkers.

At its most basic level, a biomarker is any measurable biological molecule or function indicative of a disease state. Doctors use common markers such as temperature, blood pressure and cholesterol to monitor overall health. Today, researchers are applying this idea to proteins in the body. By measuring concentrations of these biomarkers, most recently, with less-invasive blood tests (versus cerebral spinal fluid), we can better understand how diseases like Alzheimer’s manifest, progress and respond to medications.

As pharmaceutical companies have been abandoning Alzheimer’s trials, a team of researchers at the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) led by neurologist Mathias Jucker found a link between the blood biomarker neurofilament light chain (Nf-L), a protein that collects in the body, and early signs of Alzheimer’s.

In the center’s study, Jucker and his colleagues detected increases in Nf-L 16 years before symptoms of Alzheimer’s were present in a cohort of patients with familial Alzheimer’s disease.

Nf-L has already demonstrated success in facilitating the early detection and/or prognosis of a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and Lewy body dementia.

This breakthrough discovery offers promise to Alzheimer’s patients, as well. While preliminary, the results mark a significant advance toward a blood test that could detect the disease well before symptoms. Early detection would completely change the equation for companies developing new therapies by enabling trials using drugs on early-stage disease when the drug has a better chance of being effective. This also gives patients more resources, including time, to make choices when it comes to treatment or preventative care.

Scientists are carrying out similar research at Washington University in St. Louis, where thy recently reported progress toward a blood test for beta-amyloid.

Both this and the DZNE study are significant in that they showcase opportunities to not only see disease far sooner, but they do so via a blood test, with equal or better results than those obtained through expensive brain scans or invasive spinal taps.

Understandably, the potential to completely change the way we see, treat and one day cure Alzheimer’s has sparked excitement among health organizations. Just last year the FDA released guidance designed to incorporate biomarkers into the Alzheimer’s drug approval process as part of its strategy to bolster clinical trial outcomes.

The use of biomarkers to diagnose and track Alzheimer’s disease has gained support from visionaries including Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, both of whom invest heavily in the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation’s Diagnostics Accelerator, a program dedicated to advancing digital tools that could tip the scales toward a viable treatment. Likewise, the nonprofit community is equally committed to this endeavor. Powering Precision Health, which I founded, aims to transform healthcare from today’s paradigm of scrambling to treat diseases late in their progression to one focused on precision and personalized treatments early in the disease cascade. Its annual event – the PPH Summit – continues to serve as an impactful forum for the world’s most renowned researchers, clinicians, medical leaders, patient advocates and investors eager to double down on the biomarker revolution.

Biomarker research is also lending credence to the idea of a precision health approach for Alzheimer’s treatment —the theory that we need to combine technology and big data with a hands-on patient experience. This is leading researchers to explore combination therapies that could address several causes of the disease.

These developments may lead us to a multi-pronged biomarker approach, by which we detect Alzheimer’s early and closely monitor the disease’s response to treatment using a full menu of revealing markers, including Nf-L, the tau protein – which when accumulated is found to disrupt the function of brain cells – beta-amyloid and more. What’s more, similar approaches are proving successful in oncology, where biomarkers are actively being used to identify cancer and assess immunotherapy drug response. In transposing similar thinking to Alzheimer’s studies, we may be able to unlock even more insight into the disease’s origins to help us take it down once and for all.

Reclaiming hope

Despite the setbacks, patients should take solace in the fact that few people are giving up hope. I believe we have a path before us that is more promising than ever, with a robust body of research demonstrating the promise to see Alzheimer’s at—or before—onset.

The challenge ahead is to change the way we fundamentally approach treating disease and delivering patient care. We see a future in which doctors can see indicators of a disease early through routine blood testing, the same way we regularly screen for cholesterol. The hope is that patients can enroll in life-saving clinical trials before dementia takes hold.

By shifting clinical trials to earlier in the disease cascade, we are better positioned to improve success rates. It’s been shown that incorporating biomarkers as a measure for disease progression can increase the probability of gaining phase III approval by 300% following a phase I approval. Additionally, targeting treatments to fight the disease at its earliest stages requires less dosing, reducing potential exposure to toxicity and lowering the risk of adverse reactions among clinical trial patients.

We have lost so many battles in the history of Alzheimer’s research. But if this new approach teaches us anything, it’s that this is our moment to double down, learn from the failures, and support one another in thinking differently about creative solutions.