Every year, thousands of Americans face the same weighty decision. With cash piling up in a no-yield bank account, they determine it’s time to entrust their wealth to a pro. But how do they ensure they’re not handing over their hard-earned savings—and their hopes of paying for college, perhaps, or enjoying a financially secure retirement—to the next Jordan Belfort or Bernie Madoff?

To help investors vet brokers and the firms they work for, the private regulator that supervises US financial advisers offers BrokerCheck. It’s an online database of work histories, credentials, and disclosures of possible past misconduct, serving as the lone portal through which customers can check up on advisers’ records. The site reports past customer complaints of misconduct, covering everything from excessive trading to outright fraud.

BrokerCheck is supposed to give consumers the most relevant information available that might predict brokers’ future behavior. But the picture it offers is far from complete.

While the online archive does contain data that would help users check up on individual money managers, it presents the data in a way that makes it hard for users to see a representative picture of firm-level misconduct. And that information is critical to helping people avoid brokers liable to misbehave with their money, according to scholars who have recently documented how important hiring practices and institutional cultures are to predicting a broker’s likelihood of future misconduct.

The stakes are high. For misconduct cases filed from 2014 to 2016, brokers and brokerage firms paid $800 million a year, on average—over $600 million in settlements, $175 million in fines, $25 million in damages—according to Quartz’s analysis of BrokerCheck data. Other research suggests the sum reflects a small fraction of customer losses. A 2015 report by the White House Council of Economic Advisers estimated that unsound financial advice cost families $17 billion a year ($18.3 billion in today’s dollars.)

BrokerCheck is operated by an industry-run regulator. And the way it presents data has the power to distort markets and protect the profits of financial institutions. The only reason we know this is that, finally, its grip on the data is slipping.

Starting a few years ago, a handful of pioneering academics were able extract the critical firm-related data from individual profiles. It’s thanks largely to these analyses, which offer vastly more complete data on firm behavior, that we’re starting to see how little investors are being told—and how much the ignorance costs them.

The bustling business of selling investing advice

To grasp the significance of the new research, it helps first to know what, exactly, brokers do and how they’re supervised.

US households have roughly $90 trillion in total financial assets, about a third of which is held in retirement accounts. Around 17% of households use a financial professional to manage their money, according to a 2019 survey conducted by CNBC, Acorns, and SurveyMonkey. Among retirees, that share is higher, around 30%. In other words, the wealth of tens of millions of households—in particular, the ability of older Americans to retire comfortably—depends on the wisdom of their financial advisers’ actions.

Collectively, those actions could have far broader economic consequences. Savings are, in a sense, a public resource. The willingness of households to sink their savings into stocks and bonds provides a massive pool of capital available to companies, and helps dictate funding costs for businesses. Household consumption drives nearly 70% of US economic output; the financial security that encourages people to keep spending, instead of holding cash, is crucial to sustaining the current pace of growth.

In 2018, the last year for which there is data, the brokerage industry managed $24 trillion in client wealth, according to Aite Group, a research and consultancy firm. That same year brokerage firms generated $367 billion in revenue, and $45 billion in profit (pdf).

To directly trade stocks and other securities for clients, a financial adviser must be registered as a broker. In addition to securities listed on mainstream exchanges, brokers have access to a menu of financial products that, whether because of legal restrictions or exoticism, are generally beyond the reach of retail investors. These include complicated annuities, specialty bonds, unlisted real estate investment trusts, whiz-bang derivatives products, and private placements.

Most of the finance industry falls under the regulatory purview of the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Brokers and their firms, however, are directly policed by a membership-based group called Finra (a loose acronym of Financial Industry Regulatory Authority), a private, nonprofit corporation created in 2007. With the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association, Finra is among the biggest, most prominent self-regulating industry organizations in the US. Its stated goal is to protect investors and promote market integrity in a way that “facilitates vibrant capital markets.”

One way Finra strives to fulfill its mission is through policing firms and their representatives, issuing fines for violations and, in severe cases, referring criminal activity to the Feds. The organization takes an active role in investigating brokers and firms for misconduct. It also oversees the arbitration process between customers and brokerage firms—those who think their broker’s lousy choices lost them money must lodge their complaints with Finra.

Finra reported an average of around 3,050 customer grievances a year between 2014 and 2018. Many disgruntled customers wind up settling with brokerages. Those who don’t are legally required, in nearly all cases, to resolve disputes through arbitration. Settlements tend to work out better for customers. For example, as the New York Times reported, of the 2,772 complaints filed in 2013, some 2,173 were settled, with complainants receiving monetary or non-monetary relief 84% of the time. In the 499 cases that went to arbitration, 42% of customers were awarded monetary or non-monetary damages. Each of these data points reflects an event stored in BrokerCheck (or is supposed to, anyway—more on that shortly).

Finra is meant to equip “retail investors with access to unbiased financial resources and information,” according to Finra’s website. But even though the information in the BrokerCheck profiles of individual brokers might itself be unbiased, bias can emerge in the presentation and interpretation of data. And the way Finra presents data on BrokerCheck keeps key information off-limits to all but the most sophisticated and tech-savvy of users.

What BrokerCheck tells you…

BrokerCheck shows credentials and work histories of Finra’s 625,000 registered advisers, including records of past complaints, misconduct, disciplinary actions, and settlements.

These individual profiles are vitally helpful in a few key respects. Google searches seldom turn up much about individual brokers—there’s no Yelp-style archive of customer reviews to peruse. So BrokerCheck certainly fills a gap in giving customers a sense of brokers’ reputations. And it presents disclosures about misconduct allegations prominently and in an easy-to-understand format. That makes it fairly obvious when brokers have lots of red flags. (Note that disclosures don’t necessarily indicate wrongdoing; the complaints are sometimes dismissed by arbitrators.)

But the language of the disclosures is often vague, jargon-filled, and light enough on details that it can be impossible to tell whether a misconduct charge reflects a truly reckless streak or simply a bit of bad luck. Even more confusing, in the case of settlements, brokers may dispute their blame or involvement in the complaint—and the disclosures provide few clues as to the merits of such protests.

Consider this 2017 disclosure on one broker’s profile:

Allegations: Customer alleged that a transaction made in his account wasn’t authorized.

Damage Amount Requested: $17,228.90

Settlement Amount: $14,000.00

Broker Comment: The unsupported allegations are a specious attempt of a customer to recover losses from a purchase that declined in price. All transactions were previously discussed and authorized, in fact, the customer admitted that all trades were authorized during a phone conversation with the Branch Manager, then switched gears when he realized that he could recover funds in that instance.

The reasonable-sounding wording of this remark, which is typical of a broker disclosure comment, makes it hard to tell whether the customer’s claim was legitimate, since firms sometimes settle to avoid litigation expenses. BrokerCheck gives users no further information to go on. (In that example, the complaint might not have been so unreasonable after all. Within a few years of its filing, the accused broker racked up more allegations that he was “churning” accounts, or executing excessive trades in order to collect more fees.)

The information in the disclosures seldom makes clear who’s at fault—whether the broker acted recklessly or fraudulently, whether it’s the broker’s firm that should be blamed for pushing dodgy products, whether the customer’s allegations were baseless and the firm settled in order to minimize legal fees, and so on. Here’s another example of an actual disclosure:

Allegations: CUSTOMER ALLEDGES NOT HAVING THE SUITABILITY FOR THE TRADING STRATEGY.

Damage Amount Requested: $13,800.00

Settlement Amount: $13,800.00

Broker Comment: [CUSTOMER] IS NEPHEW OF MY SIGNIFICANT OTHER. THE CASE WAS SETTLED TO AVOID FAMILY PROBLEMS.

Helpful or not, BrokerCheck makes it fairly easy to review the conduct of an individual broker. Firm profiles, by comparison, are far more difficult to decipher.

Firm-level disclosures aren’t listed on the website itself. Users first must download or open a pdf file, which can run to hundreds of pages. BrokerCheck renders the information even more inaccessible by putting the arbitration award history in the bottom-most section of a linked-to pdf, after a litany of company minutiae and details about regulatory penalties. What this means is that, for bigger firms in particular, users might have to scroll through hundreds of pages of text, much of it consisting of visually sadistic descriptions entered in all-caps.

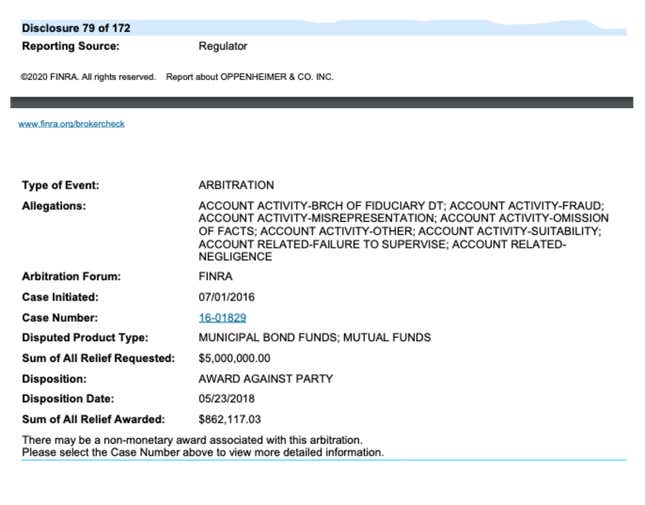

Here is how an award decision appears on the online profile of a broker and, on pages 282 and 283 of a linked-to pdf, the firm (the latter is captured in the screenshot below).

The canniest customers in search of details on disputes may find their way to Finra’s arbitration awards site, where their diligence is rewarded with pdfs that are usually spare on case specifics and dense with legalese. Brokers, meanwhile, can apply to arbitration committees to expunge disclosures from their BrokerCheck record.

But there’s an even bigger problem, which gets to the crux of BrokerCheck’s fundamental flaw. Firm profiles are egregiously incomplete, missing information that is vital to helping customers make well-informed choices.

What’s missing from BrokerCheck

In its profiles for both individuals and firms, BrokerCheck lists disputes that ended in arbitration judgments finding in favor of the customer. While the histories for individual brokers also include pending allegations, as well as claims that ended settlements, the company-level disclosures don’t. Even if a firm was partially or totally at fault, the complaint only shows up on the individual’s record, not the firm’s profile.

The different disclosure standards encourage firms to settle rather than seeing a suit through to arbitration (and thereby risking a disclosure on their firm’s profile). In theory these dynamics should benefit individual customers, if reaching a settlement yields better value than arbitration, in terms of the recovery rates. In practice, however, what is clearer is that the skewed disclosure standards allow firms to keep their records looking cleaner than they actually are. Meanwhile, brokers can, seemingly reasonably, cite their firm’s settlement in protests of innocence for any disclosures on their individual profile, shunting blame to their firm and citing their firm’s payment of arbitration determinations as evidence.

This means that in order to assemble a complete picture of malfeasance happening at a given firm, you can’t simply gather information from the company’s profile data. Instead, to get the relevant record of firm misconduct, someone must first gather the disclosure histories of all 625,000 individual, active brokers—and many tens of thousands more, including brokers who have since left the industry—extract the data, and format it before they may analyze them.

Now, it’s possible that depriving users of firm-level misconduct data doesn’t matter; perhaps it has little bearing on the likelihood of an individual’s propensity for recklessness or shady behavior. But to know for sure, we’d need to have a gander at the firm-level data. And Finra historically barred any attempt to do this.

Until recently, that is. In 2017, it relaxed its position slightly, allowing computer scripts to be used to access BrokerCheck data for non-commercial purposes (notably, this bars third parties from repackaging and selling the data in a format that might be more usable to consumers—for example, by creating rankings based on misconduct rates). The loosened restrictions came only after a handful of renegade scholars figured out how to use software to extract the critical data, and after other researchers filed records requests to get portions of the data from state regulators.

Finally able to analyze this data in aggregate, scholars have been publishing a small but fast-growing trove of research. So what do these hard-to-access, firm-level data caches reveal?

The findings are fairly consistent. Individual histories offered on BrokerCheck will only help you so much. To truly grasp the risk to one’s savings associated with hiring a given broker, the clincher is institutional context—the misconduct histories of a broker’s colleagues.

What’s hidden in the data

Let’s start with the losses. Brokerage firms (and in rare cases brokers) wound up shelling out around $500 million a year in settlements and awards, on average, between 2005 and 2015, according to Mark Egan, Gregor Matvos, and Amit Seru—finance professors at Harvard Business School, Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, and Stanford Business School, respectively—in a study published last year in the Journal of Political Economy.

Our own, more recent analysis of cases filed between 2014 and 2016 found that the industry paid more than $600 million in settlements annually and another $25 million in damages. Both amounts probably understate the losses to customers—in cases where customers settle with the broker (or, more typically, the broker’s firm), the settlement amount is often less than the claim. As for disputes that go to arbitration, committees tend to favor the industry in award amounts. In addition, BrokerCheck doesn’t require disclosures for any misconduct complaints for losses smaller than $5,000.

In a given year, only about 0.6% of US brokers are charged with misconduct, according to Egan, Matvos, and Seru, whose analysis is based on the profiles of 1.2 million brokers registered between 2005 and 2015. The researchers define misconduct as criminal or regulatory disputes that were resolved against the adviser. 1

Of course, as with any high-stakes service, a certain rate of error that winds up hurting customers is inevitable. As Egan and his colleagues point out, the annual incidence of broker misconduct is similar to that of medical malpractice.

Here’s what’s strange, though. More than half of physicians have faced medical malpractice cases at some point, according to a 2017 survey by Medscape—meaning, the odds of a doctor making a malpractice suit-level error at some point in her career is about the same as a coin flip.

But only about 8% brokers have ever been charged with misconduct, according to Egan and his colleagues. (Our own, more recent analysis of BrokerCheck data reveals that just over 7% of currently registered brokers have instances of misconduct on their records.)

In other words, a small number of chronic repeat offenders are responsible for the vast majority of the brokerage industry’s reported malfeasance. According to the economists’ analysis, a broker with a record of past misconduct is five times likelier to commit another offense than the average adviser. How are these advisers still finding clients?

An industry warped from within

Breaking down the patterns on a firm-by-firm basis makes the scope of the problem easier to comprehend. For example, from 2005 to 2015, 18.8% of the brokers at Oppenheimer had records of alleged misconduct, according to the researchers. Oppenheimer declined to comment on the findings. Over the same period, fewer than 1% of the brokers at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs had such records. (But note that this may reflect that the biggest firms tend to employ more brokers who work strictly on trading, lowering the statistical likelihood of brokers interfacing directly with retail clients and incurring misconduct complaints. Also, brokers at larger firms are more likely to get their alleged misconduct expunged (more on this in a bit).

Our own updated analysis of the BrokerCheck data—a sample that includes the histories of individuals and firms registered when we collected the data over several weeks starting in late July 2019—shows similar disparities. (The searchable table below includes data for all firms with more than 500 brokers; use the > page-forwarding function at the top right of the table to scroll through the list.)

Most firms don’t let miscreant advisers rip off clients with impunity. Nearly 50% of brokers with recent misconduct episodes left their companies soon after, according to Egan, Seru, and Matvos—compared with an average job turnover rate of 19% among advisers without. But past offenders recycle in the system because most don’t have trouble getting hired again.

About 44% of the brokers who lost their jobs after misconduct disclosures found another firm in the next year—not much lower than the 52% of financial advisers without a misconduct disclosure who found a new job within a year of leaving their previous firm. Overall, about three-quarters of advisers who have engaged in alleged misconduct are working—either at their original firm or a new one—a year later. This allows repeat offenders to coexist alongside the overwhelming majority of advisers and firms that have pristine records of customer service.

These patterns are weird. If things worked the way they do in economics textbooks, advisers who consistently lose money for their customers should swiftly find themselves out of work. In reality, though, something is preventing market forces from driving the bad apples from the industry.

How apples turn bad

Even at firms with the worst track records, some 80% of brokers have clean records. The key question is whether they’re likely to stay that way. The evidence suggests there’s a greater-than-average chance that they won’t, which is why firm-level data would be useful to investors.

“While avoiding brokers with disclosure events may be a good rule of thumb for unsophisticated investors who have access to nothing more than public BrokerCheck information, it is not sufficient,” argues a team of economists and mathematicians at Securities Litigation and Consulting Group (SLCG), a Virginia-based firm that provides expert witness services in financial-industry disputes, in a pair of analyses (pdfs).

“The 20% of brokers at these firms with a history of customer complaints do, though, increase the likelihood that another broker at the same firm with a clean record will cause investor harm in the future,” the SLCG analysts argue. “Investors need to know the disciplinary history of a broker’s co-workers.”

Say there are two firms—Company A, where one out of every 10 advisers had a misconduct disclosed last year, and Company B, where two of every 10 had a disclosure. The next year, we would expect Company B to have a 30% higher likelihood of misconduct the following year than Company A, all else equal, according to SLCG’s analysis. While this is by no means perfectly predictive, the risk implied by these industry patterns is essential for someone choosing which firm to work with. Or as SLCG puts it, “The BrokerCheck reports for most of the brokers at [the six highest-risk firms] should prominently display a skull and crossbones warning.”

Why is firm-level behavior so predictive of individual integrity? Perhaps because shady behavior is “contagious,” as Stephen Dimmock and William Gerken—finance professors at Nanyang Business School in Singapore and the University of Kentucky’s Gatton College of Business, respectively—documented in a 2018 article published in the Journal of Finance. To examine how financial advisers influence each other’s behavior, the economists looked at trends in adviser misconduct before and after mergers between financial adviseries (pdf). (They define misconduct as a customer complaint that resulted in the settlement of at least $10,000 or an arbitration decision in favor of the customer.)

Their findings were startling: Advisers were 37% likelier to commit financial misdeeds after they encountered a new co-worker with a history of malfeasance. The “contagion effect” was almost twice as strong when the advisers and their new co-workers were of the same ethnicity—which the researchers suspect may be because people with similar backgrounds are likelier to interact more.

These patterns illuminate at least one reason bad behavior tends to emerge in concentrated pockets. But why do any firms take chances on advisers with misconduct records in the first place?

Hotbeds of bad advice

It could be that some advisers earn black marks because they tend to take more risks—and, as a result, generate relatively more rewards for most of their clients. There’s no empirical evidence of this, but it’s a reasonable theory.

However, research by Egan and his colleagues flags a more sinister dynamic at play. Their analysis reveals that rates of misconduct are higher in regions with older, richer, less-educated residents. This, they surmise, may reflect bad actors targeting groups that tend to be less financially sophisticated.

Another analysis finds that some brokerages seem to pursue strategies that boost revenue at their customers’ expense. “These firms appear to have adhered to a high-risk business model,” SLCG said in its 2017 study, “resulting in problematic products as well as specializing in problematic brokers.”

SLCG’s analysis of malfeasance reveals some stark patterns. One big culprit, its analysts say, are illiquid products like non-traded real estate investment trusts (REITs), tenants in common (TIC), equipment leasing, variable and indexed annuities, and other private placements. Indeed, firms with the worst records are more than five times likelier than the average firm to receive customer complaints about illiquid investments, according to SLCG.

Another big category of customer complaints falls on the other end of the liquidity spectrum: equities products, including stocks traded on public exchanges and over-the-counter securities. Companies accused of shady trading involving these products skew more toward charges of excessive or unauthorized trading in client accounts.

Of course, making BrokerCheck more transparent might not directly change this dynamic; after all, investor savvy is shaped over decades, and can’t hope to be improved through a website.

By relying heavily on BrokerCheck, Finra’s regulatory strategy is to “assume markets work and that markets will police bad actors. To some extent, that does work,” says Colleen Honigsberg, a professor at Stanford Law School. But that’s not enough. “The market does discipline,” she says, “but it doesn’t discipline all the way.”

Mind you, Finra requires brokers to make investments that are merely “suitable” for customers; a broker can legally choose products that financially benefit him—for example, by ignoring no-fee mutual funds in favor of those that charge transaction fees passed on to the broker—as long as such trades are deemed appropriate to the client’s broad financial situation (This, by the way, is at the heart of an ongoing political debate over whether brokers should instead be required to satisfy a “fiduciary duty” to do what is best for the client, a standard to which other licensed investment advisers are currently held.)

Who controls the past?

However essential misconduct complaints are to predicting future transgressions, they don’t always remain public for long. This is because Finra allows brokers to wipe misconduct incidents from their BrokerCheck profile—and, by extension, the reconstructed firm record—through a process called “expungement.”

The purported aim of this mechanism is to allow wrongfully blamed advisers to clear their records. In aggregate, expungement should therefore make BrokerCheck more accurate—meaning, brokers whose records are wiped should, on average, continue to stay clean.

Stanford’s Honigsberg and Matthew Jacob in the economics department at Harvard University used the newly accessible BrokerCheck data to evaluate how many financial advisers accused of misconduct use this “expungement” process to have the incident struck from the record—and how many of those successful in wiping their slates clean went on to allegedly offend again.

Between 2007 and 2016, brokers had made 6,660 requests for expungements, out of a total of roughly 53,000 allegations of misconduct, report Honigsberg and Jacob. Of these requests, 84% were expunged and removed from the BrokerCheck site. That adds up to nearly 6,000 episodes of possible misconduct rendered invisible to future clients searching on BrokerCheck (and, for that matter, to Finra’s own monitoring staff and state enforcement agencies).

According to Honigsberg and Jacob, brokers who successfully expunge misconduct disclosures from their records are likelier to be charged with future misconduct than those who are denied 2—and are 2.5 times more inclined than average to engage in future misconduct.

The expungement process, Honigsberg and Jacobs note, is expensive, likely costing most brokers somewhere between $25,000 and $50,000 for each incident. In other words, despite the gaping asymmetries of information between the industry and the public, brokerages still shell out big-time to pretty up their BrokerCheck reputations. This hints at both the underlying value of the disclosure system Finra has built and its failure to let customers realize that potential.

A Finra spokesperson says the regulator is “actively working on improving the expungement process.” tells Quartz via email. “Proposed reforms include applying a minimum fee for expungement requests, creating a special roster of arbitrators with heightened qualifications and training to hear expungement requests, and setting shorter time limits for bringing expungement requests.”

The bulk breakthrough

None of this is to argue that Finra suffers from industry capture or corporate corruption—or that it’s actively shirking its commitment to investor protection. Neither is it to argue that privately run regulators are inherently inferior to public ones. (For example, as Honigsberg notes, Finra is much more aggressive in investigating its members than some government financial regulators.)

Plus, there were—and still are—sound reasons for keeping tight control of the data. One concern is protecting the privacy of both the brokers and customers mentioned in complaint files. And since BrokerCheck is updated daily, analyses of data extracted over a period of days might draw conclusions from out-of-date or inaccurate information. That concern is why Finra began permitting the automated extraction of data from its webpages—also known as scraping—only recently and only for non-commercial uses, Finra says.

“The information in BrokerCheck has always been free and available to the public. BrokerCheck is designed for investors to help inform their decision on whether to work with, or continue to work with, an individual broker or firm,” a Finra spokesperson tells Quartz by email. “Over time, and after discussions both internally and externally, we made the decision to allow scraping of the site for investor protection, academic, regulatory and compliance purposes only.”

Despite the reforms, bulk data is still not easily available to the public because Finra effectively restricts access to those with advanced coding skills. (For instance, when Quartz requested the data, Finra told us we could only get it if we were able to extract the information from their website ourself.) Also, even if bulk data was available, few members of the public would know how to analyze the data to find relevant information about firms and advisers.

Perhaps more importantly, the terms of use for BrokerCheck data still bar commercial firms from using the data. That’s unfortunate, says the University of Kentucky’s Gerken, because the analytical services that an outfit like Morningstar or Barron’s might provide would be hugely valuable to investors.

“It doesn’t make sense for every investor to [analyze industry data] on their own,” Gerken says. “There’s a huge opportunity for third parties to come and do this—people who do the hard work and either provide it as a public good or sell it—if the data is available to them.”

Asked about why Finra does not provide its own ranking of firms in terms of their history of misconduct, a spokesperson offers the following response:

“FINRA, in its role as a self-regulatory organization, provides information about firms and registered individuals to help investors make better informed decisions about who they would like to do business with. Rankings are inherently subjective and individuals can disagree regarding the relative importance of different factors. By providing the underlying factual information, FINRA empowers investors to make their own informed decisions.”

Virtue in the face of perverse incentives

Making it hard for customers to separate trustworthy brokers from the riskier ones doesn’t just hurt savers. Upstanding financial advisers suffer, too.

After all, one truly striking finding of the new research is the fact that the overwhelming majority of brokers consistently conduct themselves beyond reproach, year after year, sometimes for decades.

Despite the perverse incentives that encourage misconduct, virtue persists. Transparency would likely help that virtue to become self-reinforcing—pushing clean brokers to cluster in firms with similarly upstanding behavior toward customers, and encouraging firms to shun brokers with more checkered histories.

Bringing BrokerCheck’s hidden data into the open wouldn’t fix everything amiss in the financial advice business. But the new research argues it is an essential step toward righting an imbalance that favors misbehavior-prone firms over the American public, and letting market forces work the way they’re intended.