But not nearly as much as Bill Clinton or Harry Truman.

The most recent US jobs report highlighted a trend that has defined president Barack Obama’s battle for jobs growth: Even as the private sector expands, reductions in the public workforce are dragging back total job creation—and economic growth.

But how does it fit in with the historical picture? Let’s start with what the president has the most control over: There have been three modern episodes in which federal employees have been cut during a presidential administration: the post-World War II demobilization under president Harry S Truman (1945-53); the Cold War peace dividend and budget cuts under president Clinton (1992-2000); and now Obama, who has downsized the federal government during the recession. Here’s a comparison:

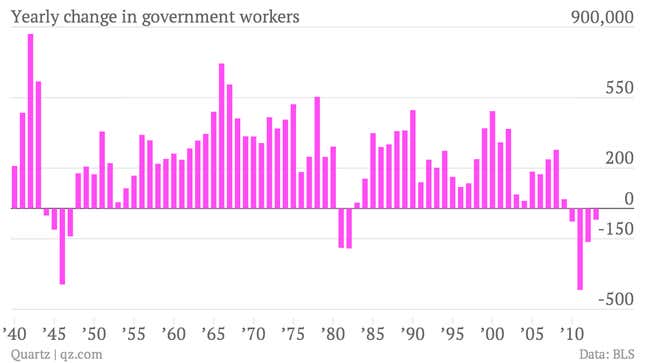

But to get a full picture of the impact public hiring has had on the economy, look at the figures for total public employment, which includes state and local employees like teachers, police officers and firemen:

Clinton’s job cuts don’t even show up—the economic boom of the 1990s allowed states to keep hiring and make up the difference—and while Ronald Reagan’s first two years of domestic cuts in 1981 and 1982 resulted in reductions of 66,000 federal workers, by the end of his term he reversed course and hired a net 240,000 federal workers. Even Truman finished his term as a net public job creator despite demobilization, with 540,000 more people publicly employed when he left office.

But Obama, five years in, still has a public jobs deficit of 645,000 to make up if he wants to break even as a government job-creator. The problem is that even as federal workers have been downsized, state and local governments haven’t seen enough growth to make up for the recession costs like they did in the 1950s or 1990s, and federal aid to states during the recession has been delivered at levels consistently lower than Obama’s requests.

Obama still has three years to hypothetically make up the difference in public job creation between himself and his two federal employee-cutting predecessors, but just to break even government at all levels will need to hire more than 200,000 workers every year until his term ends, a fairly unlikely proposition. If he doesn’t, Obama will be the first modern president to leave office with fewer people publicly employed.