For decades, hundreds of fifth graders in Montgomery County, Maryland took a test most of their classmates never had to take. The district was known for its rigorous curriculum and gifted programs for students at nearly any age and the students were vying for a spot in one of the district’s three magnet middle school programs. These schools were often not the closest to their homes, so they would have to travel farther to attend them.

About 1,000 would be accepted, about 3% of all middle schoolers in the district, and they tended to be from families that were prosperous and well informed. These students, identified as deserving special attention by the test, were also overwhelmingly white and Asian—much more so than the middle school population as a whole.

But starting in the 2016-17 school year, Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) rolled out new policies around gifted education. Instead of requiring families to identify what students would be tested, the district instead evaluated every student in second grade or older for abilities in reading and math; fourth- and fifth-graders who needed more enrichment were enrolled in accelerated classes with curriculum set by the district. Galway Elementary, in Silver Spring, was one of the pilot schools for the policy, which has since been rolled out across the district.

At Galway, the shift wasn’t too disruptive, says Dorothea Fuller, the school’s principal since 2013. The hardest part was the scheduling, since administrators didn’t want gifted kids to feel like a separate community from the rest of the school. “We don’t have students grouped together and separate from other students,” Fuller says. “We’re trying to make sure all students are exposed to a rigorous curriculum.”

MCPS is just one of several districts to change the way it implements gifted education, the result of a sweeping change in the field over the past decade. Researchers and district administrators are getting closer to resolving the issues of inequality that have long dominated the conversation around gifted and talented programs. But that may mean doing away with some elements many have long considered unassailable, including the premise of giftedness itself.

“What we’re talking about is reconceptualizing what ‘giftedness’ means in K-12 schools,” says Scott J. Peters, an education professor at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewhater who focuses on assessment.

There are about 50 million students in public schools in the United States. For the 2011-2012 school year, the US Department of Education found that about 3 million of them (6%) qualified as gifted.

Since the 1970s, federal legislation has defined who qualifies as gifted: “Students, children, or youth who give evidence of high achievement capability in areas such as intellectual, creative, artistic, or leadership capacity, or in specific academic fields, and who need services and activities not ordinarily provided by the school in order to fully develop those capabilities.”

The terminology used to refer to these students—talented, accelerated, or in need of enriched programs—varies by state or by educational philosophy, and many states and individual school districts follow their own definitions.

Experts disagree whether giftedness is something that children are born with, but most agree it’s something that can be cultivated. Educators try to identify these gifted children early in their academic careers, often by the third or fourth grade, because they are still young enough to have that talent developed, but not so young that it’s difficult to administer the assessments (i.e., they can sit still and read on their own).

Providing these children with more rigorous classwork isn’t just for their benefit, but for society’s, as well, says Jonathan Plucker, a professor of talent development at Johns Hopkins University and the president of the board of the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC). “If we’re not finding ways to get them more challenge, they kind of zone out. They don’t like school, they aren’t as intellectually engaged as they could be, they’re not developing their creative and innovative skills—all things that our culture and workforce desperately need,” Plucker says.

Though the first school for gifted children opened in Massachusetts in 1901, much of the foundational research about gifted education happened in the 1920s and 1930s, paving the way for an explosion of gifted education programs in the post-Sputnik panic of the late 1950s. Some schools offered full-day enriched instruction to students who had been identified as gifted, while others would offer it only in particular classes or in after-school activities.

But for decades, gifted education has been criticized for perpetuating inequality. During the era of segregation in the US—and even in the decades after—white parents pushed for their kids to be enrolled in these overwhelmingly white programs; black kids, meanwhile, rarely had the same opportunities. Gifted-and-talented programs earned a reputation for segregating white and so-called model minority students of Asian descent, giving them more rigorous schoolwork and smaller classes, while other students of color were left behind, kept out, or relegated to special education programs (recent research contradicts the idea that minority students are overrepresented in special education).

In many places, gifted education still does this. Black students remain underrepresented in gifted programs. In last year’s freshman class at New York City’s Stuyvesant High School, one of the best-known gifted schools in the nation, just seven black students in a class of 895. “This is not a new problem,” said Joy Lawson Davis, an independent scholar who focuses on equity and gifted education.

Even in diverse districts, enrollment in gifted programs hasn’t reflected the make-up of their schools. First, the way students were selected for gifted programs wasn’t equitable. Many school districts relied on teachers to refer students for gifted programs, but studies show teachers tend to recommend white kids more often than black kids. In districts in which students have to take a test to gain admission, white and Asian parents were more likely to know to ask about gifted programs, and able to pay up to $700 for the tests, a sum out of reach for most low-income families.

What districts do with the test results matters, too—in many districts they were evaluated against a national standard (instead of against other students in the district or school). “Using local norms doesn’t actually identify that many more kids, but the kids it does identify are more distributed” across races, Peters says. And even for those students who were selected, gifted programs might only be offered at schools farther from their homes, creating a logistical challenge for parents with unpredictable or inflexible work schedules.

Because of this history, gifted and talented education has gotten a bad rap. Some districts across the US no longer offer it and it’s hard to find a news article on the subject published in the past five years that doesn’t criticize gifted education as a way to perpetuate the systemic inequality far too common in many US institutions.

But many scholars don’t think eliminating gifted programs will improve education. That’s in part because there are still students that need more challenge in the classroom, whether or not they are enrolled in gifted programs. And when those kids don’t end up in the right programs, there are real consequences (pdf)—a lack of challenge can stunt their intellectual growth or cause them to disrupt (pdf) the classroom. “We don’t have the right to say all these gifted kids are going to make it anyway. That’s a long-held notion that has not panned out,” Davis says.

Over the past decade, schools have slowly begun to embrace new models that don’t just provide enriched instruction for those identified as gifted—they’re providing more tailored instruction for all students, in the process moving towards solutions to the inequality that seemed insurmountable for the past 50 years.

In 2015, leaders of the Montgomery County school district contacted an outside organization to audit its special programs, which had been lauded nationally. “One of the things we learned was that we have really good programs, but our [selection] processes are something we needed to reconsider or think about differently,” said Kurshanna Dean, the supervisor of accelerated and enriched instruction for MCPS.

Instead of relying on a single test, the district started looking at several different metrics for each student, such as their scores on district-wide assessments, in class, and on an external assessment to gauge their academic level.

This approach, called universal testing, had been discussed among gifted education experts for several years, and now districts like MCPS were finally implementing it. It’s emblematic of a larger shift in the field of gifted education, toward removing some of the built-in systemic barriers. Those same experts don’t agree on the impetus that brought this change about, but it’s clear that more people are prioritizing equality.

Peters isn’t sure what caused the shift, but he’s able to put his finger on what it can look like in practice. K-12 schools are moving towards an education model that offers students more individualized instruction catered to their specific needs. In this model, based on the same premise as the response to intervention model (also known as the differentiation model) used by many districts to tailor special education, schools don’t try to determine whether a child shows signs of “giftedness.”

Instead, this new model assesses students’ abilities across different subjects and enrolls them in classes based on their level. Whereas a student who qualified as gifted might attend all accelerated classes at a different school, under the new model this same student would perhaps receive enriched instruction for math but can stay in an on-grade-level class for English since that’s not a subject in which she would need additional challenge, all at their local school.

This newer model has other advantages. It can better meet the needs of students once identified as gifted because not every student needs enriched instruction for every subject. And students don’t have to take an expensive or inaccessible test for their teachers to figure this out—instead, they all take more frequent, lower-stakes assessments, taking the pressure off more deterministic tests like New York’s SHSAT, necessary for admission to Stuyvesant. Students can move in and out of services as they need them—maybe a child needs additional attention in a particular subject in third grade but doesn’t need it by seventh—and are evaluated only against the other students around them instead of the higher bar of national norms. Plus, accelerated instruction (should it be necessary) is offered right in the child’s local school, so parents won’t need to figure out how to bring their child to a distant magnet school in order to give them the most tailored education.

Universal testing led MCPS to identify nearly triple the number of children who could benefit from enriched learning, says Dean, the district supervisor. They came from every racial background, from every socio-economic level, and could be found in every school across the district. “It was a great ‘a-ha’ moment for me,” Dean says. The district had budgeted for its anticipated need for gifted programs based on its old model, where parents could ask for their kids to be tested. “When you take universal screening into account, you realize there are far more children you can serve in this kind of instructional model,” Dean said. “It was a great surprise for us.”

So MCPS started to shift to what Peters calls a hybrid model, something between the traditional gifted program and the more contemporary response-to-intervention model. Though the district still has magnet schools for the most advanced students, it also offers enriched curriculum in local schools, and partnered with outside organizations to train teachers to administer it.

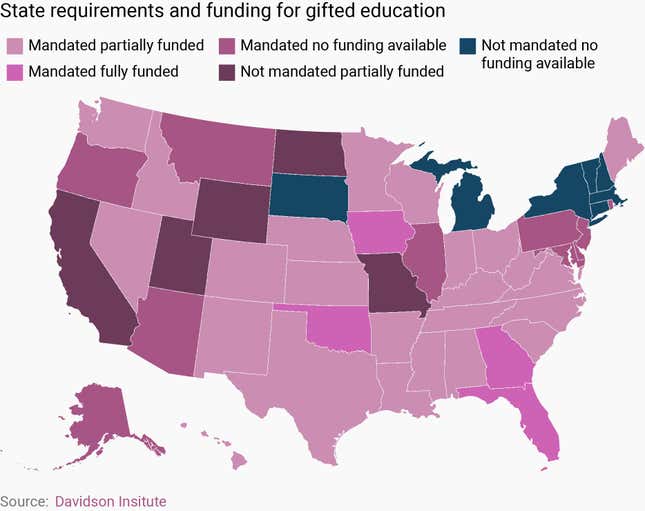

Rolling out one of these new models isn’t always seamless. Funding is a challenge across education, but it can take some fancy accounting work to balance federal and state requirements (for example, 35 states mandate gifted education, but only four offer complete funding for them) with all the ways districts could scrounge up funding, like through various federal mechanisms (funds from Title I, intended for schools with a high proportion of children from low-income families, can be used for advanced learners).

And these new programs aren’t always cheaper. While gifted kids no longer automatically require separate classes, teachers, or schools, they do have to be assessed a lot more often, which can be expensive, logistically complicated, and time-consuming, though Peters notes many programs have no additional costs beyond administration.

Another challenge: getting parents on board. To parents already familiar with the process of teacher nomination or selective test-taking to attend magnet schools, a change can seem like districts are taking opportunities for enrichment and development away from their students. “We changed the process to align more to the change in national research, and I don’t think we took the time to educate the community on our thinking and why we were moving in that direction. It looked to some like we didn’t seem transparent,” Dean says.

Testimony about the proposed changes from school board meetings shows that some parents were skeptical about the external assessment of the district’s existing programs, and were particularly concerned about the study’s recommendation (pdf) that students whose older siblings were already enrolled in a language immersion program were not guaranteed entry. “Implementing any of the recommendations would be hasty, ineffective, and a disservice to the students in the language immersion programs,” Delon Pinto, a parent to three students at Maryvale Elementary in Rockville, said in testimony (pdf) submitted to the school board in June 2016.

Dean admits MCPS could have started communicating its message earlier, soliciting feedback from parents so they felt involved. “We want parents to understand that the long-term goal is to make sure that children that need access to consistent enrichment education, and that there is more than one model for it. In the past we have said the magnet program is the only model. And I don’t think we really did the advance work to explain there are many.”

It’s understandable, of course, that parents would be touchy about changes to the gifted education opportunities to which their children have access. “We all want my child to have the best opportunities. It’s human nature,” says Carolyn M. Callahan, an education professor at the University of Virginia. “The inequities in education—a lack of opportunity, a lack of talent development, the impacts of poverty and education—all that is reflected in gifted education.”

Callahan isn’t persuaded by the response-to-intervention model. “I don’t think that putting gifted kids back in regular classrooms have served any group well yet,” Callahan says. She’s most concerned about the closure of traditional programs, because gifted kids aren’t getting the attention they need. “We had some things that worked, and instead of integrating more minority kids, we eliminated the programs,” Callahan adds.

“When you put people in a room, everyone agrees on the overarching goal and structure [of gifted education]. The implementation is where they disagree,” Peters says. Researchers who think giftedness is innate favor policies that work to uncover this giftedness, often with more selective testing or higher national standards; those who are more concerned with how children can develop high achievement are partial to regimens designed to ensure students are adequately challenged at every level.

In MCPS, the changes show early signs of paying off. Now that the first group of kids identified through universal screening are starting high school, administrators are paying attention to the choices they make, including what kinds of programs they’re applying to and how did the access to advance instruction in grade school help them make those decisions. At the very least, gifted programs are looking a lot less homogeneous than they did in the old system, when 78% of the middle school students in magnet programs were white and Asian, compared to 48% across the district. “We are seeing a greater number of diverse students in advanced course work,” Dean says, though she didn’t specify how the percentages have changed.

Other school districts around the country have implemented new gifted or response-to-intervention programs like the one now in place in MCPS. In Aurora, Colorado; San Antonio, Texas; and Yuma, Arizona, a growing number of students are reaping the benefits of these new models, thanks to a grounding in research as well as intrepid district leaders and teachers. Though Peters notes that many districts are moving away from “gifted” terminology, some of these that have embraced the more contemporary models have chosen to keep it.

“Part of the process of education is that you’re always improving and increasing what you bring to students,” says Fuller, the principal of Galway Elementary. “Believe all your students have potential. Believe that part of what we do is tap into that potential. Have structures that allow them to go beyond the ordinary. You have to take risks, and students rise to that.”

Correction: this piece has been updated to reflect more recent research about the representation of minority students in special education.