Each year has its own fad: the hoverboard, the pet rock, the…X-ray? As the Victorian studies scholar Sylvia Pamboukian writes, for one brief moment at the end of the nineteenth century, X-rays were all the rage.

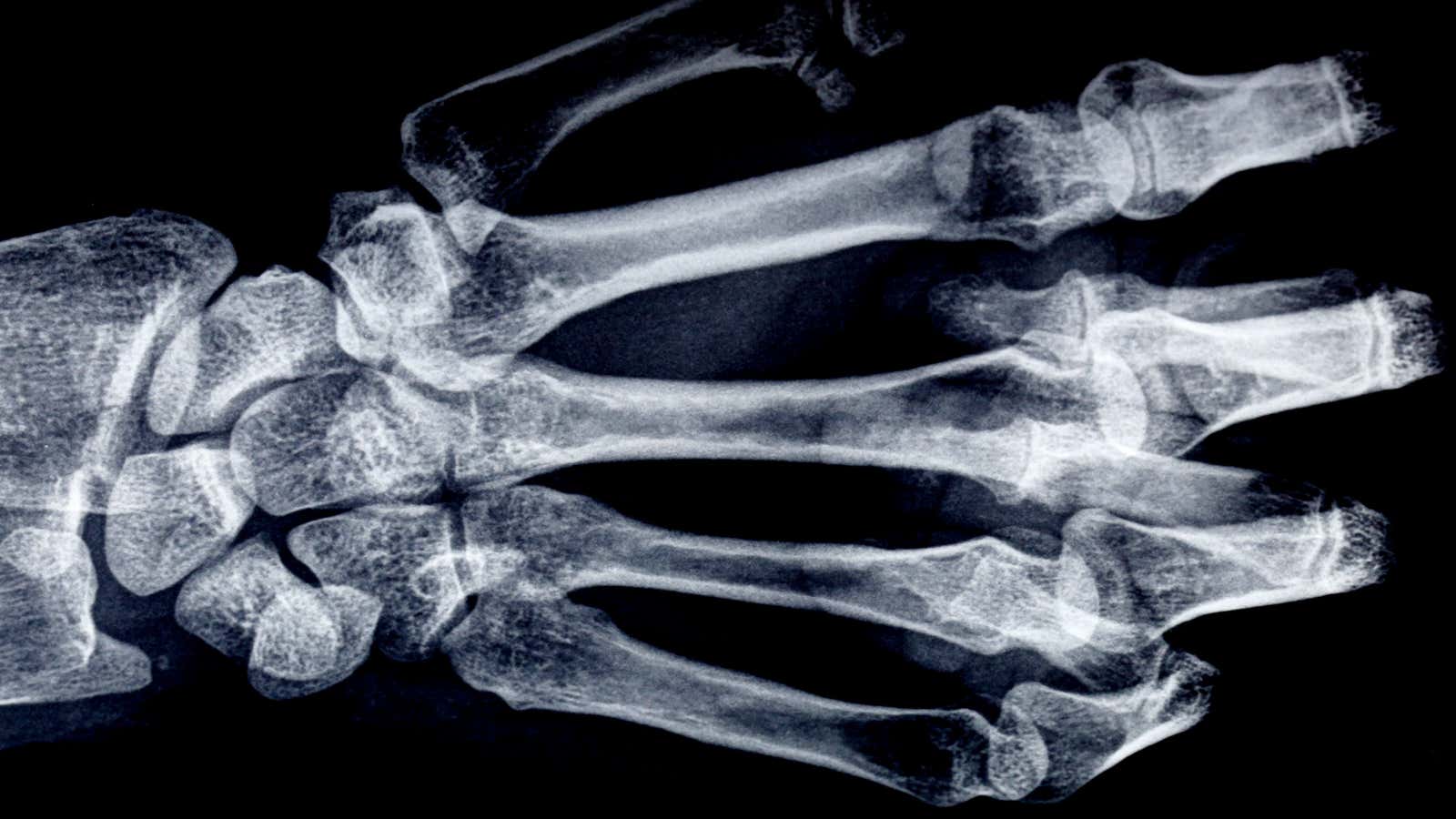

In 1895, the German engineer Wilhelm Röntgen figured out how to produce and detect electromagnetic energy in a particular wavelength range that came to be known as X-rays. Within a year, people across Britain were fascinated by the new ability to look at their own hands, stripped of flesh, with rings clearly visible around skeletal fingers.

The interest in X-rays spread through public exhibitions and lectures, where volunteers from the audience could have their hands or purses X-rayed. The fluoroscope, invented in 1896, allowed an object placed between an X-ray coil and a screen to have its insides viewed in real time. People could also buy or build their own X-ray apparatus at home.

Pamboukian writes that, for many science-obsessed Victorians, X-rays were not just a fun novelty, but a potential miracle cure. Local newspapers were eager to report on the machine’s use in diagnosing medical problems. The public also attributed germicidal and beautifying properties to the rays. Many doctors employed the rays in depilatory treatments.

By the middle of 1896, one writer in the Quarterly Review was clearly sick of the craze, writing that X-ray demonstrations “are repeated in every lecture-room; they are caricatured in comic prints; hits are manufactured out of them at the theatres; nay, they are personally interesting every one afflicted with a gouty finger.” Evidently, not everyone was a fan of the new photography. One writer in London’s Pall Mall Gazette wrote that “you can see other people’s bones with the naked eye and also see through eight inches of solid wood. On the revolting indecency of this, there is no need to dwell.”

The X-ray craze died as quickly as it was born. Within a few years, X-rays were mostly confined to medical settings. (Though, in one odd exception, shoe stores introduced coin-operated “Foot-o-Scopes”—fluoroscopes for fitting shoes—in 1920, and many continued using them until well after World War II.)

Pamboukian writes that this drop-off in interest was typical for any fad. There were, however, increasing concerns about burns, called X-ray dermatitis, reported by some people exposed to X-rays. Experiments in 1897 showed the X-rays were toxic to guinea pigs, and people who had been highly exposed to the rays soon began getting sick too. By 1910, many of the photographers and radiologists who had helped popularize the technology had developed cancer, suffered amputations, or died.

Doctors began using lead aprons and gloves to protect against the radiation. “By World War I the popular image of a radiologist included a gloved or an amputated hand,” Pamboukian writes. Presumably, that kind of imagery took some of the fun out of the wild new ability to gaze at one’s own finger bones.

This article was originally published on JSTOR Daily.