Kurdish forces seized control of the Syrian town of Kobani in January 2015 after a four-month battle with Islamic State fighters. Footage of their triumph was relayed around the world. A global audience witnessed Kurdish troops indulge in raucous celebrations as they raised their flag on the hill that once flew the IS black banner.

And so it came as something of a shock when, in October 2019, Donald Trump granted Turkey carte blanche to seize territory held by the Kurds. Consequently, what once appeared an emphatic victory for the Kurds has since descended into yet another dismal defeat.

This is not an unusual tale. Victories have also been proclaimed in the recent wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, only for violence to continue unabated.

The spectre of these apparently endless wars gives us cause to consider whether the notion of “victory” has any purchase or meaning in respect of contemporary warfare. Having spent the best part of the last decade thinking about this very question, I have come to believe that the idea of victory in modern war is nothing more than a myth, albeit an enduringly dangerous one.

As I argue in my new book, it’s high time for us to think again, and more deeply than we have done before, about what victory in war means today.

The view from Washington

The three most recent occupants of the White House offer very different views on the issue of victory. President Trump has made it both the cornerstone of his rhetoric and the lodestar of US foreign and security policy. “You’re going to be so proud of your country,” he assured the audience at a campaign rally in 2016:

We’re going to start winning again: we’re going to win at every level, we’re going to win economically […] we’re going to win militarily […] we’re going to win with every single facet, we’re going to win so much, you may even get tired of winning, and you’ll say ‘please, please, it’s too much winning, we can’t take it anymore.’ And I’ll say, ‘no, it isn’t.’ We have to keep winning, we have to win more, we’re going to win more.

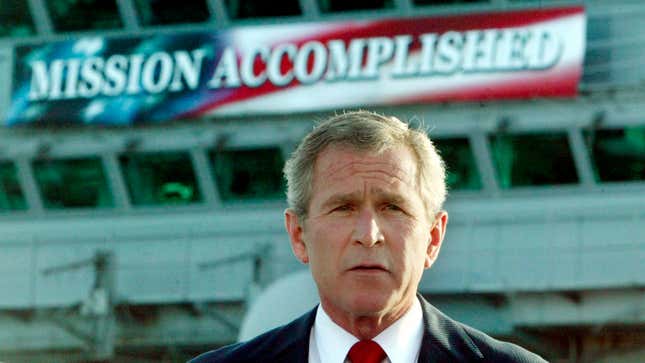

Victory also loomed large in George W. Bush’s statements on world politics. Delivering a keynote speech on the Iraq War in 2005, for example, Bush used the word “victory” 15 times while standing in front of a sign that read “Plan for Victory” and pitching a document entitled “Our National Strategy for Victory in Iraq.”

Sandwiched between Bush and Trump, Barack Obama took a very different view. Convinced that the idiom of victory was a retrograde way to talk about how modern wars end, he sought to excise it from US strategic discourse. The term “victory” is unhelpful, he explained, because it evokes crude associations with conquest and triumphalism.

The disagreement between Trump and Bush on the one hand, and Obama on the other, runs deeper than a mere difference in rhetorical style (or lack thereof). It reflects profound uncertainties about the appropriateness of the language of victory to modern war.

Since the early 20th century, the view has emerged that, when it comes to the mechanized mass slaughter of modern warfare, nobody wins. As Aristide Briand—prime minister of France for periods either side of the first world war—put it: “In modern war there is no victor. Defeat reaches out its heavy hand to the uttermost corners of the Earth and lays its burdens on victor and vanquished alike.”

Bao Ninh, a veteran of the North Vietnamese Army and the author of one of the most moving war novels of the 20th century, The Sorrow of War, made much the same argument, but in simpler terms: “In war, no one wins or loses. There is only destruction.”

Victory is dead…

Irrespective of whatever Bush and Trump might believe, it is certainly tempting to say that there can be no such thing as victory in modern war. It is easy to believe that war is so ghastly and so destructive that it can never result in anything that could reasonably be called a victory. Any successes achieved on the battlefield, it might be argued are likely to be both so tenuous and bought at such a bloody cost that the mere idea of calling them “victories” appears ironic.

But this can only be part of the story. It is too glib to declare victory in modern war an untenable proposition on the grounds that it can only be purchased at a terrible cost in human lives and suffering. The value of a victory may be diminished by a steep price tag, but not entirely negated by it.

For instance, while the Second World War produced a truly barbaric body count, and boasts the Cold War among its legacies, it also halted Nazism in its tracks. This, it goes without saying, must count for something. More recently, while the 1991 Gulf War arguably created more problems than it solved, it also successfully reversed Iraqi aggression in Kuwait.

My point here is a simple one: although victory can be hideously costly in modern war, and it invariably accomplishes far less than it is intended to achieve, it is not an entirely vacuous concept.

This brings us to the first of three twists in our tale. What is out of date here is not actually the general concept of victory itself, but the notion that victory is the product of decisive battles. The nature of modern warfare is not conducive to clear cut endings. Instead of yielding an emphatic victory for one side and, conversely, an incontrovertible defeat for the other, modern armed conflicts are prone to descend into protracted, drawn out endgames.

So it can sometimes be difficult to discern not only which side has won a given war but whether that war can even be deemed over in the first place. The words of Phil Klay, a writer who served in Iraq several years after president Bush had already declared “mission accomplished”, captured something of this confusion:

Success was a matter of perspective. In Iraq it had to be. There was no Omaha Beach, no Vicksburg Campaign, not even an Alamo to signal a clear defeat. The closest we’d come were those toppled Saddam statues, but that was years ago.

What this suggests is that victories no longer assume the form that they are expected to assume or that they had assumed in the past. If victory has historically been associated with the defeat of the adversary in a climactic pitched battle, this vision is now a relic from a bygone era. This is not how wars end in the 21st century.

Was victory ever really alive?

There is, then, plenty of evidence to support the view that, when it is spoken about in terms of decisiveness achieved through success in pitched battle, victory has little relevance to contemporary armed conflict.

But this is where we encounter the second twist in our tale. Some scholars claim that the vision of victory associated with decisive battle did not suddenly become problematic with the advent of the “war on terror,” nor even with the birth of modern warfare. Rather, they argue, it has always been problematic.

The historian Russell F. Weigley is the leading proponent of this view. He contends that the idea of decisive victory through battle is a romantic trope left over from the only time in history when wars were routinely decided by a single clash of arms: the long century bookended by the battles of Breitenfeld (1631) and Waterloo (1815).

Spectacular but also unique to this period of history, the set-piece battles of this era, Weigley argues, have had a distorting effect upon how war has been understood ever since. The pomp and drama of these clashes was such that they captured the imagination of military historians and the general public alike. Ignoring the fact that that attrition, raiding, and siege craft, rather than grand battles, have historically been the principal means by which wars have been waged, historians (and their readers) have been culpable of buying into (and perpetuating) a kind of Hollywood vision of war that mistakes an exception to the norm.

This excessively battle-centric understanding of warfare has taken root in the popular imagination. Most contemporary representations of war—in literature, media, art, and film—envision it as a sequence of battles leading up to and culminating in a decisive set-piece clash of the kind that the 2015 footage from Kobani ostensibly captured. This reflects a distortion of the historical record. In actual fact, very few wars down the centuries have pivoted on battles. Most have hinged on harrying, manoeuvring, and the denial of access to vital resources. So far as we fail to see this, a proclivity to “boy’s own history” is to blame.

The idea of decisive victory predicated on success in battle is simply a historical curio that, one interlude aside, has seldom had much relevance to the material realities of war.

Long live victory!

So should this be the end of the matter? Obama and all the other critics of victory have, it seems, been vindicated. It is not merely that victory, couched in terms of decisiveness and indexed to success in pitched battle, has little relevance to the vagaries of contemporary warfare, it is that (one period around the 17th century aside) it has never had any salience.

This brings us to the third and final twist in our tale. While it is true that the idea of decisive victories achieved through pitched battle may be regarded as a product of lazy history writing, this should not be taken to mean that it is of no importance to how warfare is understood and practised. Even if it is just a myth, the idea of victory through decisive battle still bears significant clout. Chimerical though it may be, it still functions as a kind of regulative ideal, guiding people’s understanding, not so much of how wars actually end, but of how they ought to end.

Decisive victories may well be a rare beast, historically speaking, but they are also widely posited as the goal toward which all militaries should strive. This argument can be derived from the writings of, among others, the controversial historian Victor Davis Hanson.

Hanson, whose most recent book is a letter of support for the Trump presidency, is better known for writing several works dedicated to making the case that the idea of decisive victory through battle continues to carry moral weight in Western political culture, even though a long time has passed since it was germane in a military sense.

Hanson traces the idea of decisive victory through battle to classical Greek civilization and argues that it reflects the longstanding belief that the best way for communities to settle intractable disputes is to send citizen armies to face one another across an open battlefield and there fight it out. By confronting one another in a kill-or-be-killed scenario, societies commit to testing, not only their valour and military prowess, but also the values they fight for in the crucible of combat. Any outcomes that arise from such contests, must, it follows, be respected as the verdict of battle.

There is plenty of evidence to support this view. The history of Western thinking about war from the classical world to the present day is marked by both a repugnance for the adoption of tactics that circumvent the opportunity for pitched battle, and a readiness to sneer at any victories won by those means as somehow less worthy.

In ancient Greece, Odysseus was scorned for his predilection for overcoming his enemies by guile rather than by hand-to-hand combat. In Persia, King Cyrus was similarly lambasted for relying on trickery to overcome his foes “rather than conquering [them] by force in battle.” In the fourth century BC, Alexander the Great valorized victories won by direct confrontation in pitched battles. He responded with contempt when his adviser, Parmenio, proposed launching a night-time ambush on their foes: “The policy you are suggesting is one of bandits and thieves … I am resolved to attack openly and by daylight. I choose to regret my good fortune rather than be ashamed of my victory.”

Beyond the classical world, knights in the middle ages were wont to burnish their victories by exaggerating the importance of battles and downplaying the part played by more humdrum modes of warring (such as raiding) in delivering them. These views also carried over into the canon of modern strategic thought.

The survival of this way of thinking into the present era is evident in the approbation that greets the use of those modes of fighting (such as the use of guerrilla tactics, terrorism, and drones) that preclude the finality of a decisive victory on the battlefield being achieved by either side. This reflects, I think, a lingering sense that any mode of belligerency that is not geared toward producing victory through the kind of fair fight that a battlefield contest is believed to represent must, in some sense, be morally problematic.

And so even though the ideal of decisive victory is best understood as nothing more than a myth, it still matters. It still shapes how we understand, think about, and indeed approach war. As such, it continues to guide our thinking about what war can achieve, when it should be employed, by what means it should be conducted, and how and when it should be concluded. To imagine that it can simply be struck from our vocabulary, as Obama apparently assumed, is as naive as it is foolish. But recognizing this also reveals some unsettling realities.

‘Mowing the lawn’

The ideal of decisive victory, then, is a myth, albeit an enduringly powerful one that continues to shape how we think about war. And this myth poses some dangers.

It’s a myth that tempts us to think that war can still be a conclusive way of settling disputes between societies. It invites us to believe that societies can resolve their conflicts by simply fighting them out, with the winner taking all and loser honourably accepting its defeat as the verdict of battle. The problem with this vision is, of course, that it promises too much. War is too blunt an instrument to deliver such a clean ending. In a way, then, this belief sells us a false bill of goods—one that comes at a terrible cost in blood and treasure. One need only look to the plight of the Kurds in Kobani for proof of this.

To our detriment, we appear to be both stuck with and trapped by the language of victory.

The Israeli strategic doctrine known as ‘mowing the lawn’ provides an intriguing counterpoint to this. Whereas Israeli strategists traditionally focused on procuring decisive battlefield victories against rival state armies, recent experiences in Gaza have led them to adopt a different approach.

Instead of supposing that the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) should aim to vanquish its enemies once and for all in direct combat, it is directed toward the pursuit of more modest, contingent objectives. The doctrine counsels that the IDF must treat the threat from Israel’s enemies in the same way that a gardener approaches the mowing of their lawn: that is, as a recurrent task that can never be fully completed but must instead be returned to at regular intervals.

As such, it reflects a hard-won acceptance of the fact that Israel will not achieve a final victory over its foes any time soon. In its place, it proposes that the best Israel can hope for is provisional gains—namely, the degradation and short-term containment of its enemies—that require constant and recurrent consolidation.

There are clearly very serious problems with this position—problems that I do not wish to deflect from or in any way minimize—but it does raise some interesting possibilities for how we think about victory. Specifically, it provokes us to reflect on what victory might look like if we ceased indexing it to notions of decisiveness and conclusiveness.

How might we reconfigure our understanding of victory so that it is coupled to provisional rather than final outcomes? This would presumably involve reframing it in partial and contingent rather than comprehensive terms. There is much to be said for this. But above all else, it would reconnect how we think about victory with the realities of modern warfare and a more sober assessment of the kind of goods it can deliver.

My point is not to persuade states to ape Israel’s strategic posture. It is, rather, to encourage reflection on the conundrum that victory in modern war poses.

What does winning mean today?

Thinking about contemporary armed conflict in terms of victory is problematic because modern warfare is not configured in such a way as to produce what we might regard as a clear-cut victory for one side and an emphatic defeat for the other. Construed this way, victory appears more mythical than real.

But even if it is a myth, it colors how we approach contemporary armed conflict today, tempting us to believe that clean endings are still a possibility—when they are evidently not. Victory is, in this sense, a red herring.

One solution to this conundrum would be to strike victory from our vocabularies. That is, to simply cease talking about it or in its terms. Yet this is easier said than done. As Obama discovered, the language of victory is very difficult to circumvent or evade. Just when you think it’s dead, it comes back with even greater force behind it.

The dilemma, then, is clear. Victory: can’t live with it, can’t live without it. The challenge arising from this is to rethink what we mean by victory. If, as the historian Christopher Hill once wrote, every generation must rewrite its history anew, the ever-changing nature of war demands that every generation must also rethink its understanding of military victory.

This article is part of Conversation Insights. The Conversation’s Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. You can read more Insights stories here.