November was a bad month for Uber. London declined to renew its license. Seattle approved new fees on rides and a to-be-determined minimum wage for drivers. Chicago passed a congestion tax on ride-hail services that adds as much as $3 to private rides during peak hours. New Jersey hit the company with a $640 million bill for misclassifying drivers as independent contractors.

Uber’s share price slipped by 6% in November, to $29.60. Even equity analysts, a famously optimistic bunch, have lost faith in Uber and lowered their price targets to an average of around its $45 IPO price, a mark Uber has closed above only twice since it went public in May.

Ride-hail companies have entered a new era, marked not by breakneck growth but by skeptical and emboldened regulators. Cities lost the first round against Uber, which strong-armed them into passing rules it wrote to suit its ride-hail service before anyone could figure out what was happening. Now, cities have regrouped and are flexing their muscles. One by one, Uber’s most important markets—London, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, the entire state of California—are proposing taxes and rules that one way or another make rides more expensive.

It’s hard to overstate the threat this shift poses to companies like Uber. Ride-hailing is built on regulatory arbitrage. It hires workers as independent contractors instead of employees; it circumvents many of the rules imposed on traditional taxi companies; in some countries, it sidesteps taxes on local goods and services. All these things helped make Uber’s low prices possible, and low prices are Uber’s main selling point. Closing those loopholes is bound to make rides more expensive. Wedbush analyst Dan Ives called London’s decision to withhold Uber’s license a “seismic blow.”

Uber isn’t the only company under threat. Juno, a three-year-old ride-hail service in New York, shut down in November and filed for bankruptcy protection after failing to find a buyer. Juno blamed its financial trouble on a wage floor for New York City ride-hail drivers that took effect in February, arguing it increased costs, lowered drivers’ hourly pay, and led to a significant drop in ridership. Lyft, which operates only in North America, is also exposed. Lyft and Juno both sued New York earlier this year over its driver pay rules. In California, Lyft and Uber have each pledged $30 million to fight a new law that makes it harder to classify workers as independent contractors.

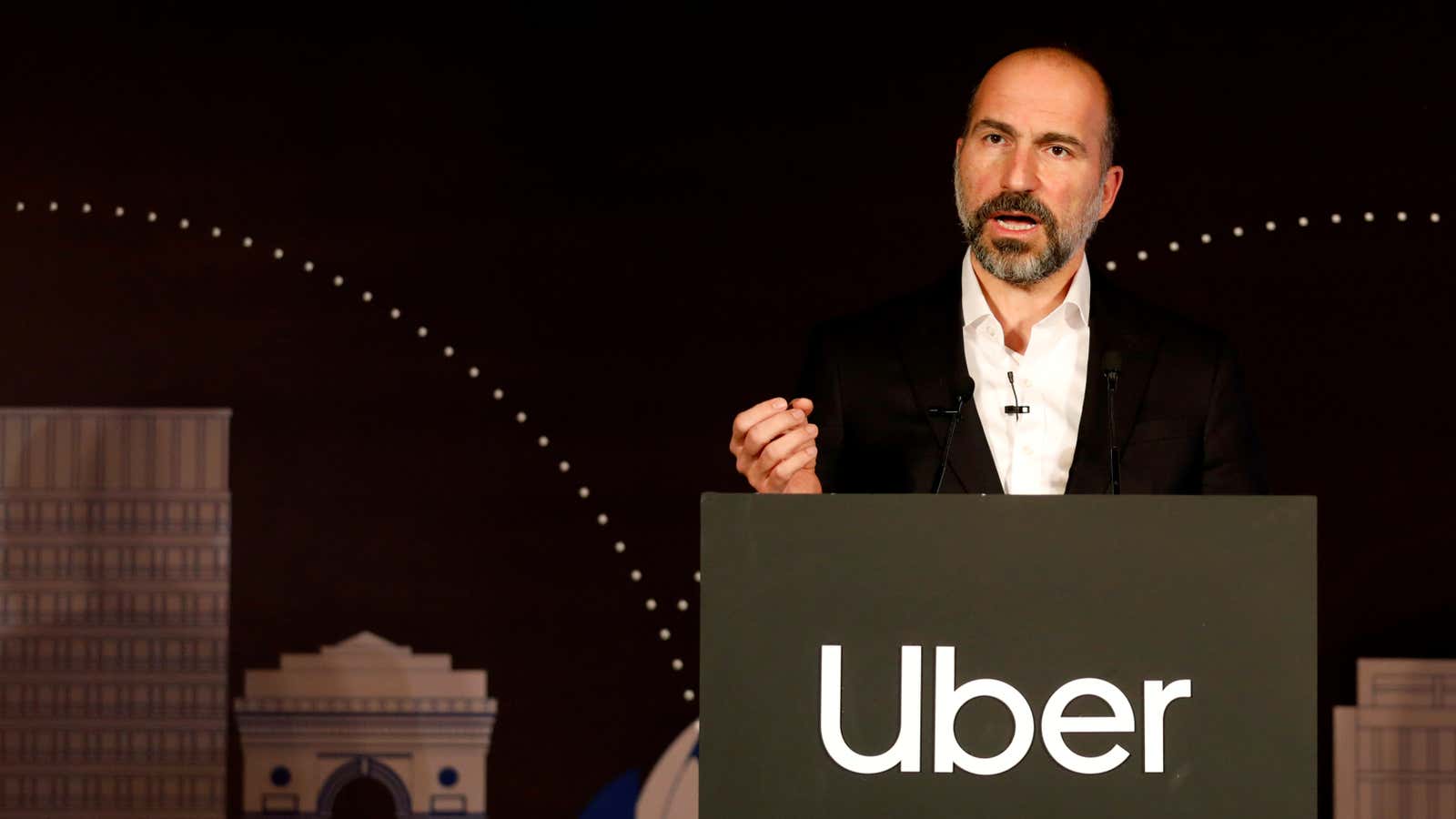

Lyft said in an emailed statement that it is committed to working with legislators on policies that preserve “the economic opportunity, unique flexibility and reliable service that people have come to expect from the platform.” Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said on the company’s third-quarters earnings call that Uber remained focused “on positive, productive engagement with regulators around the world.”

For nearly a decade, all of these companies—Uber, Lyft, and various other competitors that have cycled through the space—prioritized growth and left profits for later. The strategy contained an implicit assumption that profits would come more easily with scale; that more cities and bookings meant more clout with regulators; and that thin margins were fine because they could make money with volume. The reality heading into 2020 looks precisely the opposite: more rules, more taxes, and more costly protections for workers. If Uber never figured out how to make money in a decade of loose oversight, how will it fare when regulators start paying attention?

Correction (Dec. 3): A previous version of the chart showing Uber’s quarterly operating income incorrectly showed the company’s nine-month result in the third quarter of 2019 instead of that quarter’s result alone. The correct figure is -$1.1 billion, which is now reflected in the chart. A previous version of this story also incorrectly stated that Uber recently updated its terms of service to have drivers agree it is a provider of technology, not transportation services. This language is not new.