Ever noticed how few rivers you can see in most city centers? It’s easy enough to spot the big, usually tamed, main river such as the Thames in London, the Seine in Paris, the Aire in Leeds, or the Don in Sheffield. But you will be hard pressed to find any of their tributaries.

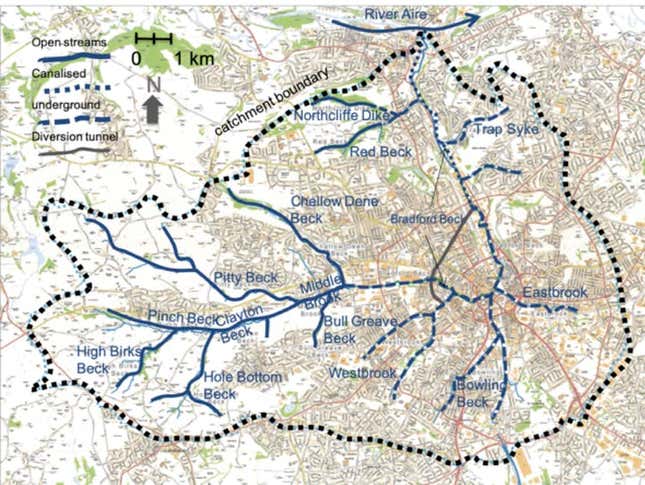

In the UK, the lost rivers of London are well known, but all cities have them. In my home city of Bradford there is virtually no trace of the small main river, the Bradford Beck, or most of its urban tributaries. In Bradford alone, more than 25km of streams have been covered over and now flow within an engineered structure known as a culvert.

Rivers were put in culverts partly to contain the smell. Bradford grew from a town of 15,000 in 1800 to 100,000 by 1860 as it became the richest city in England on the back of the wool trade, yet the first mile of public sewer was not laid until 1862 and first sewage works not completed until a decade later. Until then much of the sewage and industrial waste ended up in the Beck or canal which must have smelt appalling—it is said the canal was so putrid that it could be set on fire.

Rivers were also put in culverts to make flat land available. Buildings were constructed over the river itself, combined with raising the boggy land of the flood plain with ashes and other wastes. In Bradford at least, most of the culverts are under buildings rather than roads or public spaces. They often have a wall down the center of the river, indicating that the two owners built out to the edge of their property.

Culverts were mostly built by the Victorians

“Daylighting” is the action of returning a culverted river to open water. At its simplest it is taking the lid off the culvert, but most designs aim to create a more natural river shape and re-introduce ecological habitats.

It makes sense to do this now that the benefits of Victorian-era culverting have given way to modern problems of old age, pollution, capacity and blockage, and the loss of the pleasure of water. No engineering structure will last for ever—culverts have to be maintained and eventually replaced if the buildings and infrastructure above are to be safe.

Victorian culverts were built when cities were smaller and less of the ground was paved. Nowadays flood runoff is much greater even before we consider climate change, but the culverts’ flood capacity has not increased. This can have serious consequences, as in Newcastle a few years ago when an overwhelmed culvert collapsed and washed out the foundations of two blocks of flats built over it. An open river will have a higher flood capacity than a culvert, and a slight overflow certainly won’t have the catastrophic consequences of a blockage or collapse.

Culverts also help conceal pollution sources. For example, Bradford has more than 50 sewer overflows and many more frequently unmapped drains from roads and factories. Most of these discharge into culverts without anyone seeing them.

It is not surprising that there is widespread pollution from misconnected drains and malfunctioning sewage infrastructure that we don’t discover until the river eventually emerges downstream into the daylight. This problem is definitely not unique to Bradford or to the UK. If rivers were daylighted and visible the pollution would be more obvious and easier to fix.

Dawn of daylighting

Colleagues and I have been researching the impact of “deculverting” for a over a decade now, most recently in a review of evidence published in 2018.

In the 96 urban projects the review looked at, daylighting was mostly driven by a desire to create new habitats, to reduce flood risk, provide new amenities, and as part of regeneration projects. Water gives a sense of place in a city, and often becomes the focus for civic activities. Wildlife will return to the city—even if it is just ducks.

Many successful daylighting projects have been suburban or parkland sites such as the opening of 900 meters of the River Alt in Liverpool. Major urban daylighting projects are rarer—the opening of the Roch in the center of Rochdale to reveal the river and a 14th-century bridge is a notable recent example.

One particularly impressive example is the Saw Mill River in Yonkers, a suburb of New York City, where $34 million was allocated to opening the river to create a public park and habitat for migratory fish. Consequential redevelopment along the new corridor is reshaping the city.

A lovely small example is the creation of a pocket park on the Porter Brook in Sheffield, costing a more modest £400,000 ($526,000). As a senior Sheffield City Council official said to me, having this completed example has made it easier to explain the idea and value of daylighting to developers, and further projects are now planned in the city.

Earlier generations culverted—and killed—their rivers for reasons which were good at the time. But times have changed. Daylighting offers the opportunity to reduce flood risk and bring water and nature back to towns and cities.

David N Lerner has received funding from EPSRC, NERC, BBSRC, EU, the Environment Agency and various water utilities. He is a trustee of the Aire Rivers Trust and the Chair of the Friends of Bradford’s Becks.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.