Constellation Brands is a New York-based brewing company that produces beverages around the world. In 2016, it announced plans to build a state-of-the-art brewery in Mexicali, Mexico, to export its Mexican beer brands, including Corona and Modelo, to the US. Community leaders gushed about the 700-plus permanent jobs it would create, hailing the $1.5 billion project—expected to send 58 million cases of beer to the US in its first year—as evidence of the local economy’s vibrancy.

“Mexicali is growing like it never has in its history,” crowed Baja state’s economic development secretary, Carlo Bonfante, “and part of the reason is that Constellation Brands is coming to the city.”

Nearly four years later, the brewery is nearing completion—and under siege as a flashpoint in the increasingly contentious struggle between corporations and community groups over the fate of the world’s most-precious resource: water.

The location has become the site of sometimes-violent protests by community activists unhappy that a multinational aims to export the region’s water for a profit. The state Senate has weighed holding a referendum on whether to allow the brewery to open. In September, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador jumped into the fray, criticizing the desert town’s authorities for granting Constellation a permit in the first place.

Constellation spokesman Michael McGrew says the activists are making “false and inaccurate” claims about the brewery’s impact. He says an independent analysis has found the brewery won’t hurt water supplies, and that many local residents support the project.

“We continue to make good progress towards the completion of our Mexicali brewery and look forward to continuing to work with members of the local community to build a brighter and more prosperous future in Mexico,” McGrew wrote in an email.

Versions of what’s happening with Constellation are playing out more frequently in cities and villages around the world, and understandably so. Water—its availability, quality, and ability to inflict harm—has quietly blossomed into a frontline concern for corporations of all kinds.

Water-risk management has become a discipline for a growing number of multinationals. They’re reporting those risks to assertive, water-conscious investors, collaborating with rivals to recharge stressed watersheds and embracing their roles as water stewards. No one wants to be branded a water scofflaw or see a costly plant or other asset limited or “stranded” due to a lack of water or the license to use it.

The more ambitious are tackling the world’s water woes with an eye for doing well by doing good. Some large companies are launching new business units and products—or reconfiguring old ones—to capitalize on what ails the world on the water front.

There are funds targeting innovations to help solve acute water problems, new efforts to calculate individual companies’ water risks for investment purposes, and a growing community of startups hoping to use digital technologies to identify and fix water-related problems.

More than one investor calls water “the petroleum of the 21st century”—a commodity with the potential for increasing scarcity value.

For this guide, we look at various ways companies and investors are confronting the challenges of a water-stressed future. The world’s water woes are at once a risk to be managed, measured, and massaged, a problem to be solved, and a potential opportunity.

Table of contents

The world’s water woes | All (water) politics are local | Businesses’ role in the crisis | Water-related risks | Investors are watching | How companies are responding | Mapping water risks | Supply chains | Prices vs. value? | Water stewardship | Finding opportunity | Final thoughts

SHARK’S TEETH

The world’s water woes

The world has a severe freshwater issue. Seventy-one percent of the globe is covered in water, but just 3% of it is the freshwater vital to life as we know it, and only about one-third of that is available for human use, according to CDP, formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project, which tracks corporate sustainability statistics.

The sheer volumes used are huge. The US, for example, uses roughly 1,000 gallons per-person, per day. That goes toward power generation, irrigation, industry, and, of course, household use.

Climate change, population growth, booming manufacturing and agriculture growth, and no small amount of mismanagement have left freshwater quantities and quality under pressure seemingly everywhere.

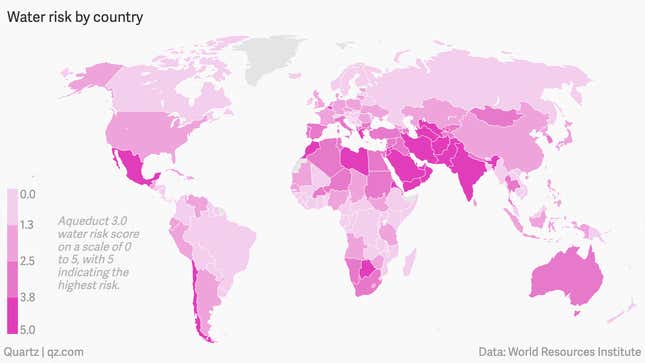

A color-coded map published by the World Resources Institute’s Aqueduct project has almost all of India, vast swaths of northern China and Africa, and scattershot locales in the rest of the world covered by the deep maroons that signify “extremely high” water-stress levels, where locals use more than 80% of available surface and groundwater in an average year.

The United Nations reports that about 4 billion people experience severe water scarcity at least one month of the year, and estimates that by 2030 up to 700 million people could be displaced by intense water scarcity. In India, a study by NITI Aayong, a government think tank, predicts that by 2030 water demand will be twice as high as supply.

Things are equally bleak on the water-quality front. The UN estimates that 80% of waste water is released back into the environment without being adequately treated. The problem is especially acute in big cities, where population growth is outstripping the infrastructure’s ability to manage it.

A 2017 study by the World Health Organization and Unicef found that 30% of the world’s population lacks access to “safely managed” water systems. And it hits the poor disproportionately. Water is important enough that if you’ve got money you’ll find a way to get it.

At the same time, floods and droughts are getting more severe. In just one month, March 2019, the insurance industry reported more than $8 billion of losses tied to floods in about a dozen countries, including the U.S., Brazil, Iran and Indonesia. One oft-repeated phrase in the water world is that if climate change is a shark, water is the “shark’s teeth”—the thing that actually delivers the damage.

HEAVY STUFF

All (water) politics are local

It’s a global crisis-in-progress that, by its nature, is intensely local. Water is heavy, which means it’s extremely expensive to transport. With a few exceptions—including a project in China that would move 45 billion cubic meters of water per-year from the south to the parched north—no one is moving water vast distances. In other words, you’re stuck with what the local watershed will provide. If it runs low or gets polluted, everyone in the area suffers. There’s no global water trade to fill in the gaps.

It happens in the US, where residents of towns like Flint, Michigan and Newark, New Jersey have been dealing with lead-contaminated drinking water. In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom has labeled the fact that 1 million state residents (many of them in the agriculture-rich San Joaquin Valley) lack access to safe drinking-water a “moral disgrace and medical emergency.”

And it’s happening with ever-greater frequency elsewhere—from Beijing, where 40% of the water is so polluted it’s “essentially functionless,” to Johannesburg and New Delhi, where open defecation and poor sewage treatment reign. Cape Town’s 2018 march to “Day Zero,” the date at which the entire city would literally run out of water, captured global headlines. Residents were limited to 50 liters of water per day for eight months, with the city publishing intricate guides on how to get by.

In Chennai, an IT and manufacturing hub on India’s Bay of Bengal, a languid 2019 monsoon season and groundwater depletion sparked a water crisis that had local officials transporting water by trains and trucks. Some officials warn that Bangalore, an even bigger IT hub, could be next.

WATER, WATER, EVERYWHERE

Businesses’ role in the water crisis

Most modern-day manufacturing and production processes rely on water—to feed animals and raise crops, to clean, heat and cool plants and outputs, or even as part of the product itself. That potentially makes corporate operations both a primary cause of water trouble, and vulnerable to all sorts of water-related risks.

Some of the numbers are jaw-dropping. It takes nearly 40,000 gallons of water to make a car, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency. By some estimates, the typical smart phone requires 3,000 gallons; a pound of beef 1,800 gallons (you’ve got to feed those animals crops, which take water to grow).

Levi Strauss, the jeans maker, says the life cycle of the typical pair of jeans, from cotton crop to laundering, consumes 1,000 gallons. A typical large semiconductor-manufacturing operation goes through nearly 5 million gallons of water per day, according to China Water Risk, a Hong Kong-based nonprofit.

In the U.S., just 12% of the 322 billion gallons of freshwater used per day in 2015 went to “public supply,” which includes most residential use, according to the USGS. Most of the rest was devoted to industrial or other business uses, including thermoelectric power (41%) and agriculture (37%).

“Certain industries have larger water footprints,” says Kirsten James, water program director for Ceres, a nonprofit that works with investors and companies to encourage sustainable business practices. “But no industry can survive without a clean, sustainable supply of water.”

The potential economic ramifications are staggering. According to Will Sarni, CEO of Water Foundry, a well-known water consultancy, 22% of global GDP is generated in water-scarce areas—a figure that is expected to climb to 45% by 2050.

RUNNING OUT

Water-related risks

Until the 1990s, water was an assumed resource, there for the pumping either directly from the source or via the local utility, which almost always charged a pittance for the privilege. No company gave it much thought.

Today’s water stresses, combined with industry’s reliance on water, have changed all that, creating a volatile cocktail of risks that need to be weighed in a company’s strategic decisions—something that can directly impact the bottom line. CDP estimates that in 2018, companies suffered $38.5 billion in water-related losses—a figure that many say underestimates the toll and is expected to grow with time.

In the worst case, plants can be shuttered or production stalled. It happened to Coca Cola, where pollution and groundwater shortages last decade near a bottling plant in Plachimada, India, sparked protests and led to the plant’s closing. After regulators in the drought-stricken Indian province Tamil Nadu authorized PepsiCo to withdraw 400,000 gallons per day from a local river in 2016, drought-plagued farmers rose up in protest. A legal challenge temporarily shut down the plant, though a court later lifted the injunction. As a local journalist said, “It is unethical and immoral for a resource that is so vital to life to be commodified.”

In Peru, where by one count 15 mining projects have been delayed by community opposition to water impacts, Newmont Goldcorp, the world’s largest gold miner, was forced in 2011 to halt gold and copper mining operations at its Conga project in the northern part of the country. Newmont has faced similar issues this year with its Penasquito mine outside of Monterrey, Mexico.

Protests are far from the only source of disruption. Floods in Chile earlier this year crippled big mining operations—something that seems to happen every year or two—costing Freeport McMoRan, a big mining company, days of output.

Droughts, can affect logistical or supply chains in ways that can dent profits and threaten growth. Olam International, a Singapore-based commodity trader, attributed a 36% earnings decline in the second quarter of 2018, in part, to a drought in Argentina that hurt peanut suppliers. In each of the last two summers, droughts have led to reduced water levels along Germany’s Rhine River, causing shipping bottlenecks and other problems for the region’s big chemical and oil companies and sparking a broader economic slowdown.

“There was no water to ship their goods, so they had to shut down production. That’s a real water risk with a significant bottom-line impact,” says Peter Adriaens, a University of Michigan professor and co-founder of Equarius Risk Analytics, a startup that measures water risks for investors.

In 2018, the same drought also forced K+S AG, a big maker of potash, to halt production at a facility along the Werra River in southern Germany for 64 days. Water levels fell so low that the plant was banned from discharging waste water into the river, which it needs to do. The loss estimate: roughly €1.5 million ($1.7 million) per day.

MARKET MECHANISM

Investors are watching

These disruptions have not gone unnoticed. Managements and boards are under pressure from a growing list of outsiders, led by investors and NGOs, who are demanding that companies step up efforts to mitigate and disclose potential water risks. The scrutiny is growing. A limited number of banks have begun to weigh water risks as part of their loan underwriting processes, meaning they could be charged higher rates.

In the near future, companies with poor water-management practices could be punished by the market. As a September report from analysts at Moody’s Investors Service warned, mining companies face increased risks of facility closures due to water availability and pollution concerns, which could affect share prices and access to capital.

Ceres, the investor network, publishes an “investor water toolkit” that guides members through the nuances of incorporating water risks into investment decisions. It also publishes industry studies, such as its recently released “Feeding Ourselves Thirsty” report that ranks food and beverage companies on how well they incorporate water risks into governance, strategy, and supply-chain management.

Adriaens’ Equarius is developing an algorithm to help index-fund managers better understand individual companies’ water exposures. Investors would buy the index, which would include stocks weighted by their water risk. “If the company has a high water risk, you’d reduce its allocations in the index,” he explains. “Its price-earnings ratio would decline.”

It’s also becoming more common to see water-related shareholder resolutions on proxy statements, prodding corporations into deeper examinations of the tolls that their operations exact in water-stressed areas and disclose those findings.

Earlier this year, shareholders voted on a resolution that would have forced Chevron to address the effects of its operations on humanity’s “right-to-water,” and outline the effectiveness of its tracking of “adverse impacts” on that right. Exxon shareholders likewise voted on a resolution that would have required the company to publish a report on the public health risks of petrochemical plants in flood-prone areas. Neither measure passed, but companies and boards must respond—both because of the scrutiny, and because incidents like Constellation’s protests in Mexico are happening with greater frequency.

Disclosure is improving. In 2018, 2,114 “high” water-impact companies and investors disclosed data to CDP on their efforts to manage and govern freshwater resources. The good news: that was up nearly 50% from 1,432 just two years earlier. The bad: CDP asked 4,969 of them for data. Clearly, there’s still a ways to go.

REPUTATIONS AT STAKE

How companies are responding

Aware of the potential disruptions, a growing number of companies are embracing water-risk management as its own discipline, staffed with experts and fueled by data.

Water risks are typically divided into three categories: the physical (quality and quantity), regulatory (local officials imposing limitations or changing prices), and reputational. No company wants to be the local bad guy when it comes to water (although plenty still are).

The reputational risks are among the largest in the beverage industry, says Sarni, the consultant. “If you’re extracting it, putting it into a bottle and selling it, the people in the community know the difference between what you paid for it and what you’re selling it for,” and it’s typically a pretty big gap, he says.

But for many other companies it’s about the physical risks. If there’s enough clean freshwater to go around in a given locale, then not only will operations face lesser risk, it also will be easier to avoid the regulatory and reputational blowback.

Companies don’t publicize what they don’t have to, but consultants say water-risk assessments are influencing corporate decisions on such topics as M&A activity and where to site plants. In 2015, Starbucks proactively moved a bottling plant for its Ethos water to Pennsylvania from water-stressed California in response to drought conditions.

“Locating a plant in a location that’s somehow insulated from water sensitivities can be a differentiator for companies that incorporate water-management into their strategies,” says Ivan Lalovic, CEO of Gybe, a startup that is developing satellite technology to monitor water quality in lakes and wetlands.

The problem, of course, is that quality and quantity are under pressure in a lot of places, which makes it difficult to confront on a global scale. Any multinational that’s big enough to merit attention is going to have operations in some water-stressed areas.

Managing it all is part-art, part-science. The field is new enough that approaches employed by big companies vary. While some might view water risk as its own classification, many incorporate water into their broader enterprise risk management systems. At General Mills, the maker of Yoplait yogurt, Wheaties and other packaged foods, water risks are watched closely, but as a trigger for bigger risks in its ERM program, such as business interruption or commodity-price volatility, not a standalone endeavor.

“If a plant gets shut down, it could be caused by water, political instability or trade. They all create the same risk,” says Jeff Hanratty, General Mills’ applied sustainability manager. “We’ve assessed the impact of that end result in advance.”

Because the execution required is so local, internal methodologies and processes can be complicated. The strategic direction might be set at the board or upper-management level, with initiatives cascading down to business-unit levels and then local geographies. For large companies, it can be difficult to folks at the top to grasp what’s happening on the ground in, say, Brazil. “It’s very tricky and complex to manage,” says Stuart Orr, freshwater practice leader for the World Wildlife Fund. “No company ticks a box and says, ‘Ok, we’ve done water,’ like they do with other environmental assessments. It’s too complicated.”

DRY DATA

Mapping water risks

Many companies start the risk-assessment process by overlaying publicly available water-stress maps with the company’s own operational maps, then studying the ones that appear most vulnerable. There’s a host of water-risk maps and tools available to help companies with the task. NGOs, including WRI’s Aqueduct, the WWF and the UN CEO Water Mandate, have free-to-use online frameworks and filters that offer anyone with a computer and some curiosity the ability to delve into to risks associated with water, all the way down to a specific address.

Some private companies are in on the act, as well. Ecolab, a Fortune 500 seller of water management solutions, offers a “water risk monetizer” tool that helps determine the true value of water to a company in a specific location. “It allows managements to monetize the full value of water anywhere in the world and create a business case for taking action,” says Emilio Tenuta, Ecolab’s vice president of sustainability.

These efforts are often coupled with on-the-ground analytics. Nick Martin, a senior consultant with Antea Group, a Dutch sustainability-consulting firm, often visits clients’ high-risk facilities in-person to understand local regulatory dynamics and perceptions, and then factor in some hard science. “We look at the hydrology of the area. What is the structure of the aquifer? What’s the condition of the lakes and rivers? How much demand is there versus precipitation levels? What are the demographics of other users?” Martin explains.

Sarni likes to perform “sentiment analyses” on how a company’s operations are viewed locally. “From there we assign a dollar value to it: If this plant shuts down for one week, it will cost me this much; if the brand takes a hit, it will cost that much.”

PRIORITY AREAS

Supply chains

Water-related risks vary by industry and company, depending on their vulnerabilities. Some are less concerned about their plants than local supply chains. General Mills estimates, for example, that 99% of its water risk comes from local farmers near its plants. If they can’t grow grains, nuts and other inputs needed to make the company’s products, the local operations won’t survive.

The company performs water-risk assessments of all global operations once every three years to identify geographies where key ingredients, such as oats, cocoa or almonds face the greatest water exposure.

The most-recent effort led to eight areas—three in China, four in the US and India’s Ganges River valley—being designated as “priority areas,” where General Mills collaborates with NGOs and other multinationals to address water-scarcity issues. The board’s public responsibility committee gets progress reports three times a year on those efforts.

In California, home to the world’s largest almond crop, it has joined forces with companies such as Miller Coors and Microsoft to figure out how to recharge aquifers without disrupting farms. “If we lost the almond crop in California, it would seriously impact our Nature Valley [granola] business,” Hanratty says. “You can’t buy all those almonds someplace else.”

Levi Strauss, which makes jeans and other cotton-intensive clothing in high-water-risk geographies like Pakistan and China, recently began pressing local farmers to get more water-efficient or risk losing its business. “What we’ve said to our suppliers is that if you’re in a high-risk water location, by 2025 you need to reduce your absolute water use by 50%,” said Michael Kobori, Levi’s vice president of sustainability at an October Aquanomics conference in New York.

A FAILURE OF CAPITALISM

Prices vs. value

Spend much time talking with folks in the water world, and you’ll hear about the pricing dilemma. Water is underpriced pretty much everywhere relative to its value. For corporate bean counters, that can make it difficult to account for water-related risks or justify investments in technologies that are more water-efficient or better at treating waste water.

Water’s nature is at the root of the problem. It’s a social good, a human right, and a key economic input. People can’t survive without it. In a sense, it’s an entitlement like air.

The difference is that while air pollution can be addressed globally—cutting carbon emissions in Cincinnati has the same effect as cutting them in Berlin—there is no global market for water. The dynamics tend to make water universally cheap relative to most other vital resources, like oil.

But water is so central to so many corporations that it’s almost impossible to put a value on, because without it there would be no operations. Reconciling the cost of water with its value is an accounting conundrum that can cloud management’s ability to make accurate judgments.

The WWF’s Orr tells of one executive he met last year who said he wasn’t worried about water “because the price is so low. I said, ‘Boy, you really don’t understand this, do you? When your asset runs out of water, is that an issue?’ And he said, ‘Of course it’s an issue.’ Well, guess what? That’s about value. Price isn’t going to tell you that.”

Many companies attempt to get around the problem by determining risk-adjusted “internal prices” that do a better job of reflecting water’s value to the operation. When Microsoft opened a data center in San Antonio a few years ago, for example, it went through a pricing exercise to help decide what water to use for cooling. With help from Ecolab, it analyzed factors like water stress in the area, other companies in the watershed, energy costs, groundwater recharge levels and local biodiversity to come up with a risk-adjusted price that was 11 times greater than the actual water bill—in this case, $848,000 versus $75,000. Armed with that information, the company concluded it would save $140,000 per-year and save 58 million gallons of potable water by investing in technology that uses recycled “graywater” to cool the data center, as opposed to freshwater.

“If a business can monetize the risk, it can measure and manage it proactively,” Ecolab’s Tenuta says. “You can’t make decisions based simply on the current market price.”

ON BRAND

Water stewardship

Stewardship is another big water-management watchword, alongside risk and pricing. Pretty much any multinational worth its salt today—from Constellation and Coca Cola to Microsoft and Ford Motor Co.—boasts a robust stewardship program that includes everything from working with NGOs on groundwater recharge schemes and supply-chain sustainability to venture funds that search for innovative solutions to water issues.

Such efforts promote the resiliency of local operations, but also double as good PR—a way to buy off the local population and gain a license to operate in the community. “It helps to be associated on the brand level with being part of the solution,” says Sarni.

Microsoft is working with the Nature Conservancy in Chennai—which regularly encounters both flooding and droughts—to help restore lakes and wetlands. The goal is to “boost the flood capacity of lakes, increase groundwater recharge and improve water quality through natural filtration” via wetlands, says Paul Fleming, Microsoft’s water program manager.

“Fundamentally we’re looking to minimize the impact of our operations and maximize the impact of our products and policies,” Fleming says. “We recognize that we’re consuming water in water-stressed areas, and we’re making investments to minimize it.”

Microsoft, along with General Mills, Miller Coors, Target and others, also is part of the California Water Action Collaborative, which promotes corporate stewardship and aquifer recharge programs in the Golden State.

BULL MARKET

Finding opportunity

The world’s freshwater dilemma, with its risks and pricing challenges, looks pretty glum for the corporate world. Yet water is so important that opportunity surely must lie in finding solutions. At least that’s the way many companies and investors are playing it.

The global water market is projected to generate revenues of $744 billion in 2019, according to Frost & Sullivan, a consulting firm. That was up from $695 billion in 2018. The figure includes municipal and industrial expenditures on pipes—the US alone boasts 3.5 million miles of underground pipe—waste water treatment chemicals, equipment and a generation of digital technologies.

“Clean water is the resource that will define the next century, like oil defined the last century,” says Matthew Diserio, president of Water Asset Management, which manages $65 million of investments in water-related businesses.

“Investing in water today is like buying bonds in 1983,” Diserio adds. “There’s a multi-decade capital investment super-cycle underway. If it doesn’t continue, we’re all screwed, so it’s a good bet.”

For some corporations, that means building businesses and products that can capitalize on a water-stressed future. Consumer products company Procter & Gamble, for example, sent teams to study Cape Town during its Day Zero troubles and walked away with ideas for “waterless” shampoos and detergents, which it intends to market in other countries. “Water scarcity can be a great driver for innovation,” Virginie Helias P&G’s chief sustainability officer, said at the Aquanomics conference

Orbia Advance Corp., a $7 billion Mexican industrial company, makes and markets PVC pipes and conservation-minded drip irrigation systems. Mindful of water-scarcity concerns, it recently repositioned a couple of business units as water-problem solvers. “There’s an opportunity for us to help solve some of the world’s water-scarcity and—security issues with our products,” says CEO Daniel Martinez-Valle, noting that up to 70% of the water transported into some cities is lost through leaky pipes.

Innovation is seen as the magic bullet to addressing the world’s water problems. The Frost & Sullivan report notes that digital solutions are driving much of the market’s growth. “Digital technologies are the big play that’s going to make us more efficient and effective with every gallon of water, because we now know on a real-time basis how much we’re using and what the quality is, as opposed to finding out after-the-fact,” Sarni says.

Startups employing predictive analytics, machine learning, satellites, and other new water-management tools are flourishing, often with incubation from large companies or NGOs. So, too, are those that focus on reusing water. “Water is a renewable resource,” Sarni says. For everyone, “the days of use-it-once-and-discharge-it are quickly disappearing.”

AB InBev, the brewing company, has partnered with a venture fund to create the 100+Accelerator, which provides grants to early-stage firms that are focused on sustainability issues, including water. The Nature Conservancy’s Techstars Sustainability Accelerator provides both funding and mentorship to firms with promising ideas in areas like real-time data and analysis, new water treatment solutions and water reuse.

Startup Gybe, a Techstars graduate, uses satellites to read data from sensors located along the shores of lakes and wetlands that use reflected light to determine changes in water quality, which can be acted on in real-time. Gybe presently has only a handful of customers, including the city of Salem, Oregon and the US Navy, but CEO Lalovic has big plans. “We want to scale this up to a point where we can provide actionable information to the general public—like a Weather Channel provider for water quality,” he says.

A DAILY MIRACLE

Final thoughts

If water is so widely underpriced, where will the returns come from to attract capital and bankroll these needed improvements? “At the end of the day, there’s almost always a technology solution,” says Reese Tisdale, CEO of Bluefield Research, a water investment research firm. “The problem is the costs and what people are willing to pay for it.”

The water system is one of those daily miracles we take for granted. It’s also absolutely the best deal in town—many people pay less for it than what they pay for a cell-phone contract or a couple of moderately priced meals. That can make it almost an afterthought. Yet without it, life is impossible. I’d pay just about anything for it if I had to, and I’d venture you would, too.

Water is no less important to the survival of many corporate operations. As Carlos Brito, CEO of AB InBev said at the Aquanomics conference, “No water, no beer.” His business, and many others, would cease to exist without it.

The capital for improving the world’s water systems will come from somewhere, because it must. NGOs and social investors—the kind that are willing to accept lower returns for a beneficial outcome—are likely sources. Corporations, too, seem willing to pay some of the freight, lest they meet the fate of Constellation Brands, or worse. But they need to do more.

We live in a water-stressed world, and that isn’t going to change. What does need to change is how water resources are managed—and, when possible, priced. That’s a local governance issue, and companies have what local leaders crave: jobs and the promise of economic development. Leveraging that influence to press for better water governance practices could benefit both communities and corporations themselves.

“They’re in the best position to catalyze positive change,” says Paul Reig, WRI’s director of corporate water stewardship.

Doing good on the water front could pay off for companies and investors by helping them to do well.