Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft failed to rendezvous with the International Space Station (ISS) during a critical test flight today in another setback for the aerospace giant.

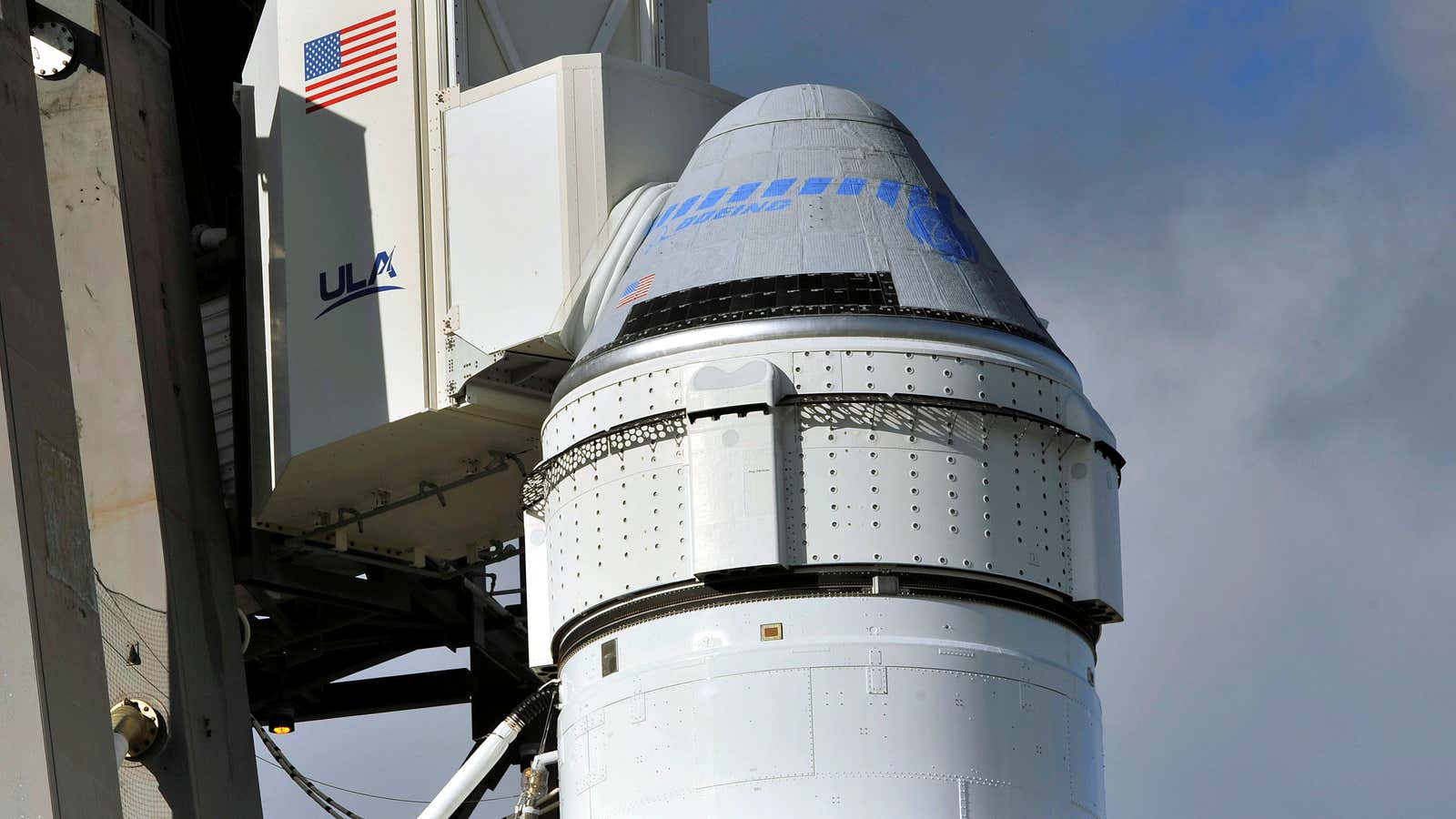

After beginning its maiden voyage into space from Kennedy Space Center onboard an Atlas V rocket, the Starliner successfully separated from its booster and set a course for the ISS.

Then a malfunction occurred, according to Boeing and NASA officials.

The spacecraft’s internal clock appears to have become unsynced with the mission plan, and so the Starliner failed to autonomously fire its engines at the correct time to drive it toward the space station. The vehicle was cut off from ground communication at the time thanks to nearby satellites, so it missed a backup transmission of the command.

Because Starliner failed to use its rocket motors at the precise moment and continued on its path, it lacked the propellant to raise itself to the altitude of the ISS, and missed its only opportunity to demonstrate that it could safely reach the orbital outpost. That is the nature—indeed, the point—of a test flight, and engineers at Boeing and the US space agency will use the opportunity to learn more about the vehicle before they put people onboard.

Still, for Boeing, the malfunction caps an annus horribilis. It is still attempting to convince regulators its best-selling plane, the 737 Max, is safe, and to complete delayed and over-cost defense and NASA contracts.

It’s not clear yet what went wrong with the Starliner’s clock or how much of the flight test program they will be able to complete before they attempt to return the spacecraft to Earth—at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico—in the days ahead. The timer problem, however, could lead to problems with the engine firings needed to re-enter the atmosphere.

The Starliner was created as part of NASA’s commercial crew program, which hired Boeing and SpaceX to develop privately-operated transportation to the ISS so that NASA could focus on deep space exploration. This test marked the finale milestone for the Starliner before it began ferrying people to low-Earth orbit on a regular schedule.

The program, now two years behind schedule, is critical to maintaining US presence in low-Earth orbit. SpaceX launched its successful rendezvous with the ISS last year, but still needs to complete an in-flight abort test before it can begin flying astronauts.

Starliner’s future path is unclear. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said he thought Boeing could fly Starliner with astronauts even if it had not demonstrated that it can dock with the ISS.

That’s surprising, given the intensity with which NASA treated the first matings between the ISS and SpaceX’s two Dragon spacecraft and Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus spacecraft. The risk of destroying the $150 billion-plus station and endangering lives onboard both vehicles moving at orbital velocity was considered too much for anything more than the most deliberate approach.

Wayne Hale, a retired NASA engineer who worked on the space shuttle program, said on twitter that the situation reminded him of a glitch ahead of the first flight of that vehicle in 1981—”an error that went undetected in ten thousand hours of software testing.”