In the hours after an American airstrike killed Qassem Soleimani, the powerful major general of the elite Iranian Quds Force, the world is braced for how Iran might respond. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said the country had already settled on a plan.

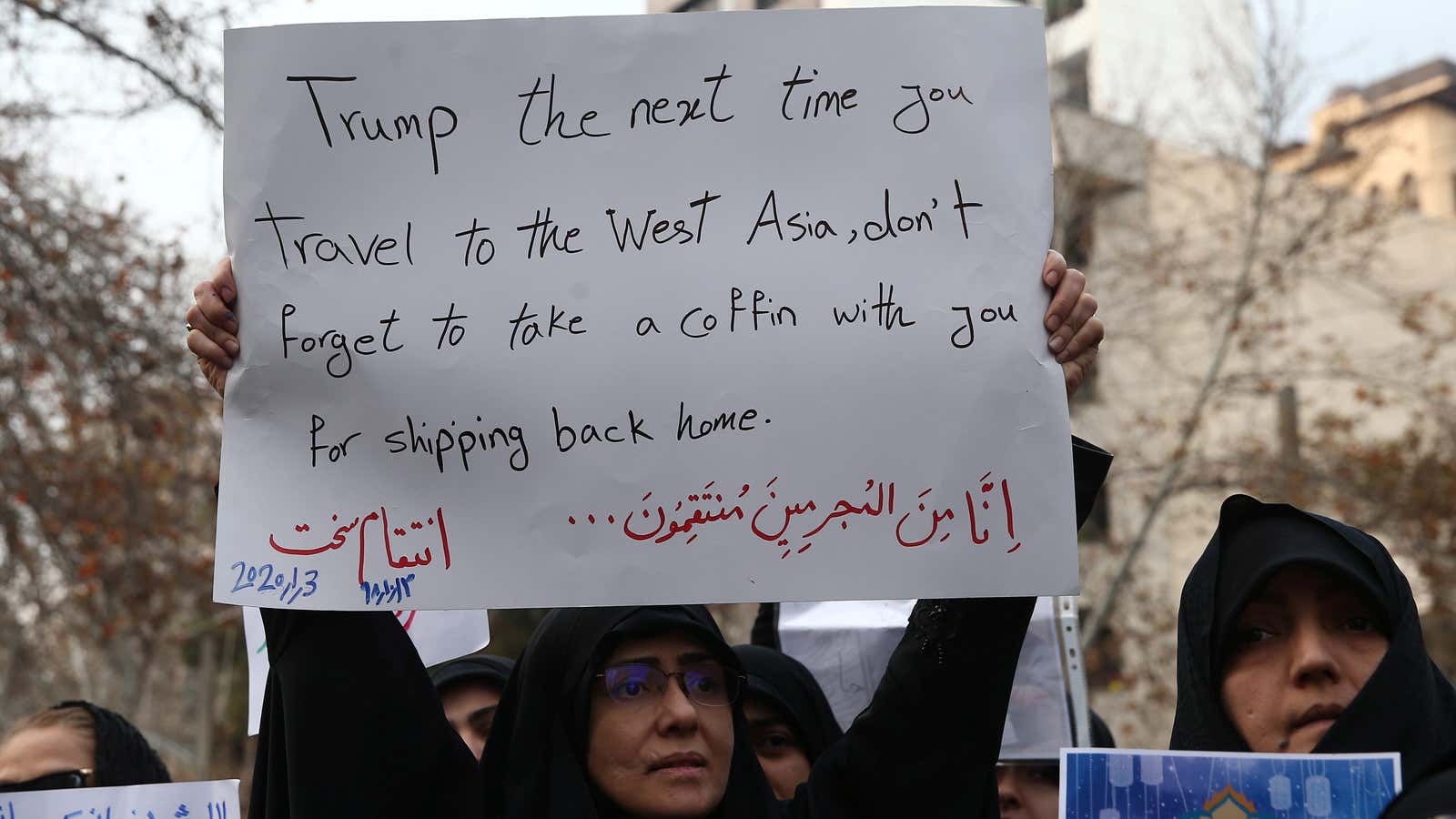

“A forceful revenge awaits the criminals who have his blood and the blood of the other martyrs last night on their hands,” Khamenei said in a statement.

If, when, and where this retaliation might take place, and in what form, is at this point anyone’s guess. Iran is a major power with a sophisticated military that could launch attacks on American personnel or interests anywhere in the region. It is also a pragmatic country that likely wants to avoid an all-out military conflict with the United States.

One option the country has at its disposal outside of traditional weapons, and which worries US officials, is a cyberattack. And that could happen anywhere.

Iran has proved adept at such strikes before.

In 2012, in apparent retaliation against US sanctions, the country attacked Wall Street banks with denial of service attacks, knocking their websites offline. In 2015, Turkey blamed Iran for cyberattacks on its electric grid, which shut down power for some 40 million people. In 2017, dozens of parliamentary email accounts in the UK were compromised by a cyberattack linked to Iran. And earlier this year, Iranian hackers managed to steal terabytes of data from a US government contractor.

In June, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) warned of a “recent rise in malicious cyber activity directed at United States industries and government agencies.”

“Iranian regime actors and proxies are increasingly using destructive ‘wiper’ attacks, looking to do much more than just steal data and money,” CISA director Chris Krebs said in a statement at the time. “These efforts are often enabled through common tactics like spear phishing, password spraying, and credential stuffing. What might start as an account compromise, where you think you might just lose data, can quickly become a situation where you’ve lost your whole network.”

After the assassination of Soleimani, Krebs cautioned network administrators to “brush up” on Iranian tactics, techniques, and procedures, known as TTPs, and said Iranian hackers could target critical national infrastructure, or CNI.

Sam Curry, the chief security officer at Cybereason, a Boston-based computer security firm founded by three former members of Unit 8200, the Israeli military’s storied cyber warfare wing, said an Iranian cyberattack could come in various shapes and sizes. As with any form of asymmetric warfare, not knowing where the strike will land is the real issue, he said.

“They’re not going to start developing now the attacks that they’ll use, they have developed them already,” Curry told Quartz. “It could be military, could be civilian—the initiative now lies with Iran to pick and choose among the options they have. Will they retaliate in kind? Send a message of escalation? The question is, what and where and when?”

The United States has carried out its own cyberattacks against Iran. In 2010, a malware attack known as Stuxnet, which experts believe was jointly developed by the United States and Israel, destroyed one thousand centrifuges at Iran’s Natanz nuclear research facility.

Chris Morales, head of security analytics at Vectra, a California-based provider of technology that applies AI to detect and hunt for cyber attackers, said the United States and Iran have long been engaged in some degree of cyber warfare.

“Iran has identified cyber capabilities as part of their attack strategy a decade ago and have slowly been building up capabilities since they were hit with Stuxnet,” he said.

As a result, the global cybersecurity community is on high alert, Curry said, adding that he hopes the United States has not just given Iran a casus belli, or a “cause for war.”

“An escalating conflict would be a very bad way to start 2020,” he said.

Acting Department of Homeland Security secretary Chad Wolf said in a statement Friday that the agency was preparing for possible responses from Iran.

“The entire department remains vigilant and stands ready, as always, to defend the Homeland,” Wolf said. A spokesperson for US secretary of state Mike Pompeo, meanwhile, said the the United States remained committed to de-escalating the conflict with Iran.

Alireza Miryousefi, a spokesperson for Iran’s mission to the United Nations in New York City, did not respond to a request for comment.