The next luxury seafood item might be salmon.

Prices for the once-cheap fish are at their highest in two decades, with no sign of relief. That’s not just thanks to overfishing. Because the world long ago tapped out the wild salmon population, around two-thirds of the salmon we currently eat is farmed. Salmon farmers are now bumping up against production constraints while demand grows at 5-10% annually, according to the Financial Times (paywall).

“The rise in prices is driven by the fear of lack of supply… It’s very difficult to see substantial volumes coming through,” Piotr Wingaard of FishPool, which trades forward contracts for salmon, told the FT.

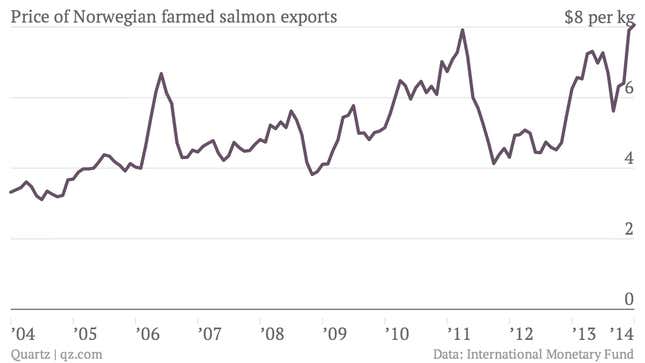

That’s already showing up in export prices of salmon out of Norway, the world’s biggest producer of farmed salmon, which are now more than $8 per kilogram ($3.6 per pound), according to Globefish.

So what’s limiting the production of farmed salmon? The surging price of fish oil, for one.

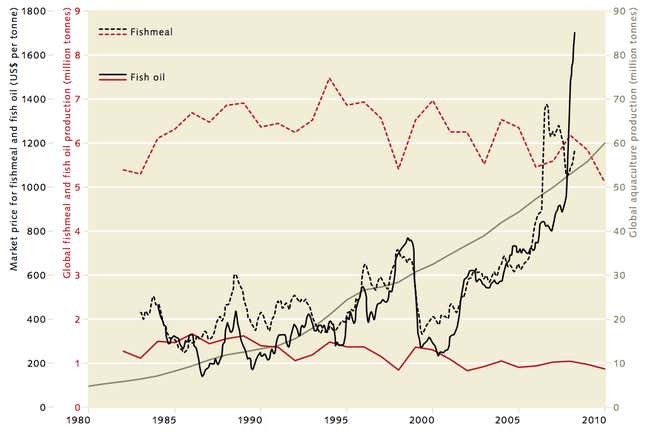

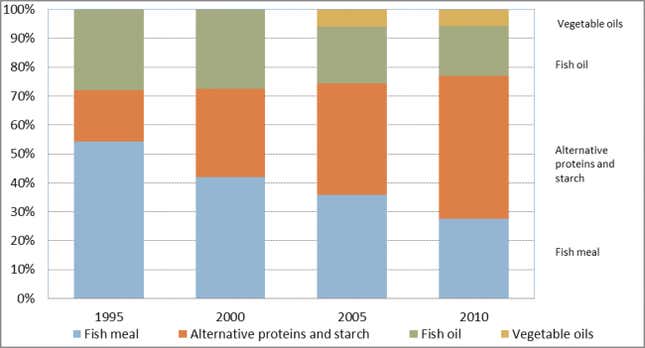

Though salmon meat is known for its omega-3 fatty acids, the famed prophylactics against heart disease, the fish themselves don’t produce them: They are built up from a lifetime of ingesting smaller organisms. Part of the problem for the industry is that fish oil production has actually decreased since the 1980s. Now the growing scarcity of fish like anchovies and sardines, from which fish oil pellets are made, is pushing fish oil prices even higher, and farmers are passing that cost along to customers.

Another reason is geography. Salmon can only be farmed in areas with cold waters, continuous currents, and sheltered coastlines (think Norwegian fjords and Scottish lochs). That has limited the major producers to Norway, Scotland, Canada, and Chile.

Then there are ecological concerns. Salmon aquaculture, as farming is known, can cause eutrophication—destructive changes to the ocean’s chemistry—and breed diseases that hurt the wild population. Sea lice infestations caused by farming can also hurt tourism. These are some of the reasons that countries have stopped issuing new permits for salmon farms.

At the same time, demand is surging, particularly from China. Norway, whose farmed Atlantic salmon still make up half the world’s salmon supply, is benefiting. It exported 3.1 billion krone ($513 million) of farmed salmon last month, says the Norwegian Seafood Council—1 billion krone more than January 2013.

Does this mean we’ve reached “peak salmon”? Probably—until scientists develop cheaper substitutes for fish oil. As the FT reports, companies like Monsanto are working on extracting omega-3 from algae and soybeans. But it’s hard to know how far off a breakthrough might be.

In the meantime, salmon supply could get much tighter. The world’s rising dependence on farm-raised salmon makes it more and more vulnerable to dramatic supply shocks caused by to disease outbreaks. These don’t happen that often, but when they do, they can be devastating. For instance, the 2007 viral outbreak in Chile drove production levels to their lowest level in nearly a decade. That caused salmon prices in the US, Chile’s biggest export market, to surge 74% between Aug. 2007 and Aug. 2010.