Where this central banker goes, a stronger currency follows

Currency markets move in mysterious ways, particularly from one day to the next. But over the long term, exchange rates generally—but not always—track interest rates, inflation and the health of an economy. What’s for certain is that no single factor, or individual, can exert a meaningful influence over the global foreign-exchange market, where some $5 trillion changes hands each day.

Currency markets move in mysterious ways, particularly from one day to the next. But over the long term, exchange rates generally—but not always—track interest rates, inflation and the health of an economy. What’s for certain is that no single factor, or individual, can exert a meaningful influence over the global foreign-exchange market, where some $5 trillion changes hands each day.

But as Bloomberg points out, where Bank of England governor Mark Carney goes, a stronger currency seems to follow. Since he joined the UK central bank in July last year, the pound has gained 7% against a basket of major currencies. Back in Canada, where Carney ran the central bank for five years before crossing the Atlantic, current governor Stephen Poloz has seen the Canadian dollar lose 6% of its value since Carney’s departure.

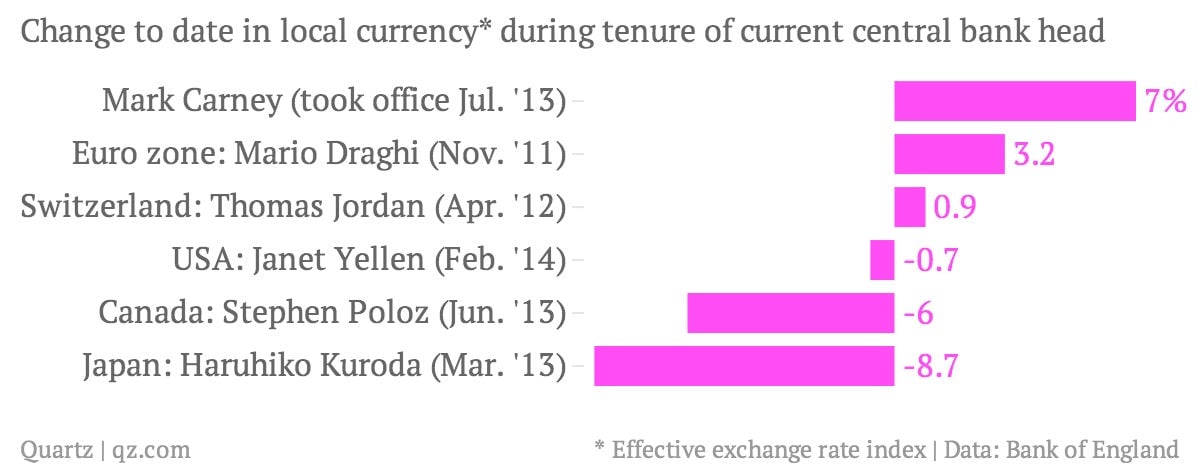

Thanks to the surprising strength of the British economy, the local currency appreciation during Carney’s time at the helm at the Bank of England puts him top of the table when compared with the tenures of his counterparts at other major central banks:

Granted, while Carney was in charge of Canada’s central bank, the trade-weighted value of the loonie slipped by 4%. But over in the UK during that time, the pound lost 16% of its value. We are not suggesting that correlation implies causation, but when it comes to currency strength, Carney’s timing is impeccable.

Central bankers generally seek stability in all things, be it interest rates, inflation, or currency values. To this end, a rapidly rising currency is not necessarily a good thing—one of the key goals of Japan’s economic policy is to weaken the yen in order to help exporters. Fearing the impact of an overly strong currency, the Swiss central bank put a ceiling on its currency in 2011 to stem any further appreciation. And so there may come a time when the relative strength of the pound makes the Bank of England equally uncomfortable.

It is exceedingly rare for someone to have experience running central banks in different countries; Canada-born Carney is the first foreign head of Britain’s central bank since its founding in 1694. It’s unlikely that many other countries will start managing their currencies by importing central bankers. But there is another move worth watching; former Bank of Israel governor Stanley Fischer is in line to join the US Federal Reserve as vice chairman, pending confirmation by the Senate. For what it’s worth, during Fischer’s eight-year reign at Israel’s central bank, the shekel gained 20% against the dollar.