The Supreme Court chief has left clues about his views on impeachment

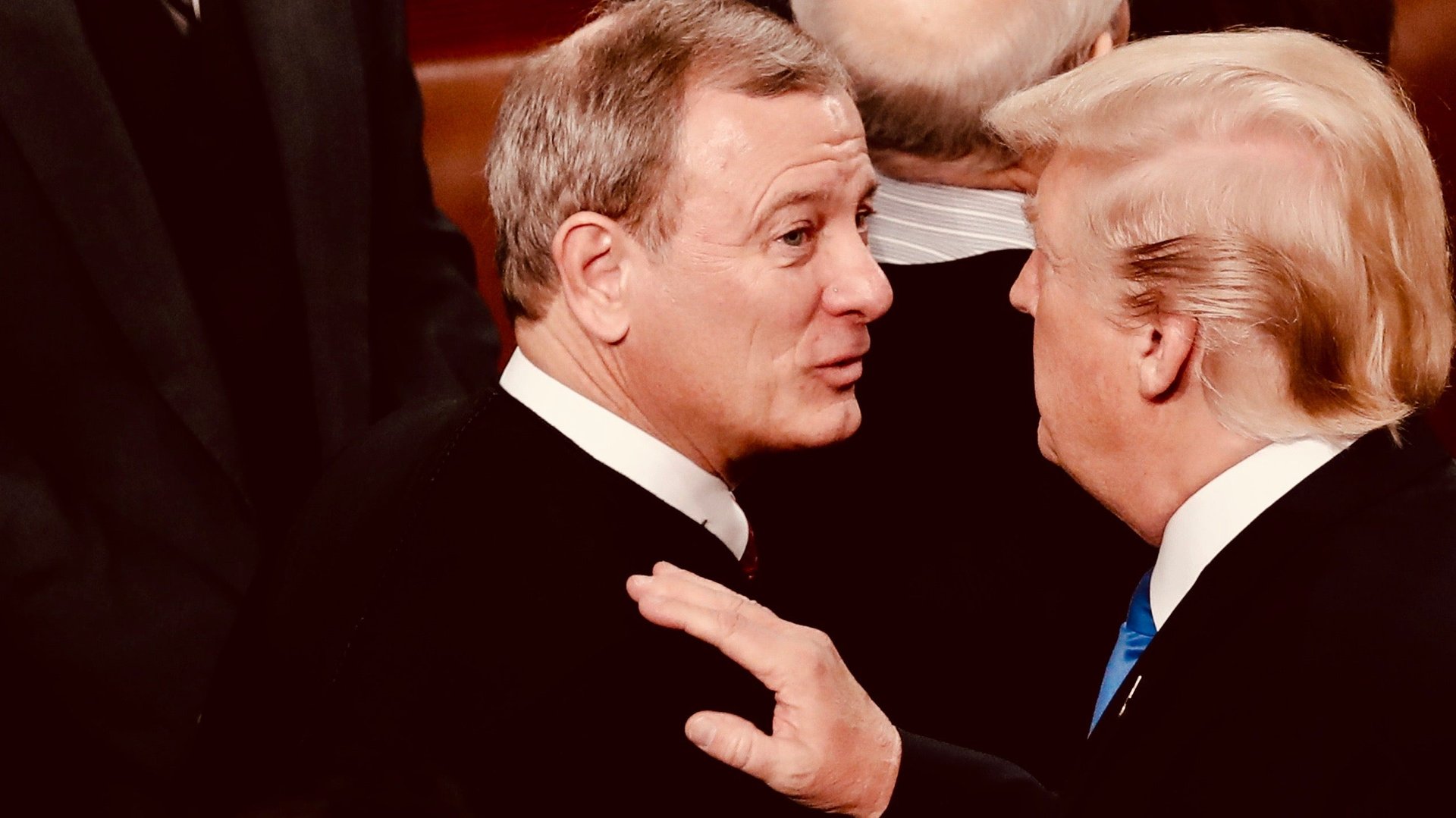

The House votes today on transmitting articles of impeachment against US president Donald Trump to the Senate, for a trial to be presided over by Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts. It’s safe to bet the chief is not relishing this looming duty.

The House votes today on transmitting articles of impeachment against US president Donald Trump to the Senate, for a trial to be presided over by Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts. It’s safe to bet the chief is not relishing this looming duty.

Roberts isn’t a big talker and he has never explicitly said that he dreads the gig. Nor has he shared his feelings about the president and his actions. But he has hinted at his thinking, and there are reasons to believe that Trump’s trial isn’t high on the chief justice’s bucket list.

For one thing, it thrusts him into the center of a political circus, which is exactly where he doesn’t want to be. Impeachment is not on brand for the chief, the Supreme Court, or the federal judiciary.

Nothing to gain

Roberts believes that courts and judges play a uniquely nonpartisan role in government. In 2018, he even issued a rare indirect rebuke of the president after Trump blasted an “Obama judge” for a decision on Twitter. Roberts proclaimed that there are no “Obama judges” or “Trump judges,” only jurists committed to the law and Constitution and equal justice for all.

Most recently, in the 2019 year-end report on the judiciary, the chief justice urged his colleagues in the courts to zealously protect judicial independence and to reflect on its importance. “We should celebrate our strong and independent judiciary, a key source of national unity and stability. But we should also remember that justice is not inevitable. We should reflect on our duty to judge without fear or favor, deciding each matter with humility, integrity, and dispatch,” he wrote.

Given the timing of the report—it came out on New Year’s Eve, shortly after the House impeachment vote, as talk of the upcoming Senate trial dominated the news cycle—some commentators read between the lines. Michael Dorf, a law professor at Cornell University, reasoned in Verdict that Roberts wanted to call out the president, writing, “In this and other modest ways, Roberts hopes to counterbalance Donald Trump; he may be a closeted never-Trumper.”

Certainly, Roberts’ annual submission was interpreted as another sly side-eye at Trump for good reason. “In our age, when social media can instantly spread rumor and false information on a grand scale, the public’s need to understand our government, and the protections it provides, is ever more vital,” he warned.

The chief justice could not have been unaware of the fact that the president is one of the people online publicizing fake news and it’s not hard to imagine that Trump’s communication style—his divisive, hyperbolic, capitalization-laden, relentless barrage of tweets—seems tiresome and problematic to the chief justice.

Roberts, after all is accustomed to communicating in long, thoughtful sentences, researched and drafted and published in opinions that have been mulled for months. He doesn’t shoot from the hip like the president and he doesn’t play to cameras, which is just one more reason he might be dreading an impeachment trial. The chief will have to contend with cameras in the Senate, unlike at the quaint Supreme Court, where filming is forbidden and reporters still scribble notes by hand while sketch artists illustrate on “small paper.”

Substantively speaking, presiding over an impeachment trial threatens to undermine Roberts’ efforts to convince the public that judges can be trusted in unreliable times. It may be difficult for people to perceive the chief as apolitical when he’s sitting in a Republican-majority Senate led by Mitch McConnell, ruling in a political proceeding about the legality of the actions of the president.

As Adam Liptak writes in the New York Times, “The chief justice’s responsibilities at the trial are fluid and ill-defined, and they will probably turn out to be largely ceremonial. What is certain is that they will be full of peril for his reputation and that of his court.”

Doing nothing well

Roberts won’t have to do too much at the trial. And if he takes his lead from the late chief justice William Rehnquist, who presided over Bill Clinton’s impeachment in 1999, he’ll do “nothing in particular and do it very well.”

The chief justice is named in the Constitution as the person to preside over presidential impeachment proceeding, but the constitutional process is unlike any other kind of trial. Roberts will theoretically make rulings on the submission of evidence, as judges do. However, he can defer to senators, invite their votes and dissent, and they can object to his rulings and overturn them.

A majority of politicians in the body—51 members—can vote against any call the chief makes and substitute his judgment. The senators can thus act as both judges and jurors, deciding on the facts and the law in this political matter.

The chief justice will be present simply because the vice president can’t preside over a trial of his boss, the president, which might result in him getting the guy’s job, because that would be unseemly and the Constitution specifies otherwise. So Roberts’ role is mostly impotent. Though he could use the position to send the same message he’s been transmitting elsewhere about the importance of impartial judges and informed public, he most likely won’t.

Writing in SCOTUSBlog on Jan. 10, University of Missouri law professor Frank Bowman dispelled the hope that Roberts will take a stand. He writes:

Despite the formal powerlessness of the role, one could imagine a chief justice thrust into the presiding officer seat who wanted to make a principled statement about the constitutional merits of the case against the president, even if that statement flew in the face of the preferences of a senatorial majority. Such a chief justice might take every available opportunity to rule in favor of, for example, the issuance of subpoenas or the production of witnesses and documents by the president. It seems improbable that Roberts would take this course. Whatever his personal views about Trump, his most likely priority will be to avoid any appearance of partiality, which might imperil his own posture of judicial neutrality and with it the Supreme Court’s institutional legitimacy.

The job of the chief justice is to take the long view. He can’t afford to let Trump’s presidency and politics generally taint perceptions of the Supreme Court. So though he may well resent the president’s approach to law and politics, he probably won’t show it at the trial and will likely attempt to minimize his influence rather than maximize it.

“As the New Year begins, and we turn to the tasks before us, we should each resolve to do our best to maintain the public’s trust that we are faithfully discharging our solemn obligation to equal justice under law,” the chief justice wrote in his report.