The Trump impeachment trial tells a bittersweet story of American dreams

It’s noon on a cold, clear day when US president Donald Trump’s impeachment legal team pulls up to a Senate entrance in black SUVs. They drive blithely to a private doorway past a gaggle of chanting protestors from states near and far bearing signs condemning their client and demanding a full, fair trial.

It’s noon on a cold, clear day when US president Donald Trump’s impeachment legal team pulls up to a Senate entrance in black SUVs. They drive blithely to a private doorway past a gaggle of chanting protestors from states near and far bearing signs condemning their client and demanding a full, fair trial.

The president’s lawyers, behind literal and figurative tinted windows, have little to fear from these people—or so they believe. The trial promises to be a short, bittersweet affair.

Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell insists on following “the Clinton model.” This means there may be no witnesses and a strictly limited record to rely upon.

Never mind that laying a record with testimony, documents, and the like—rather than prosecutors arguing based solely on a thwarted investigation—isn’t optional at trial, even in a political prosecution like impeachment (which doesn’t mirror criminal procedure). The Clinton rules were approved unanimously because everything—alleged impeachable offenses, their implications, investigations giving rise to trial, the partisan power dynamic, and the times—was totally different.

Anyway, it is widely assumed that Trump will quickly be acquitted along partisan lines, so some say the trial is a waste of time. But the process is the point of this, and cynicism is “a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Glory of the republic

What happens on this path matters, whatever the outcome. The impeachment proceedings are revealing, not only for what they show about the president and representatives, but also about the American experiment now on display—albeit in a deliberately limited fashion. We can rise to the occasion or deal with our failures, but either way we’ll see the governmental gears grind, for better and worse.

Sure, it’s frustrating that lawmakers who’ve sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution have already said their allegiance lies with the president, despite his unfounded interpretation of the founding document granting the executive power to do “whatever” he wants. But it’s also wonderful that such presidential views and the alleged impeachable offenses they give rise to are tested in public proceedings that reveal the characters, tics, and foibles of elected officials.

It’s glorious that we, the people—by which I mean me here—can dart into a Senate elevator with the president’s defenders. Trump’s personal lawyer Jay Sekulow and White House counsel Pat Cipollone greeted me with affronted glares. I stared back happily, my eyes perhaps betraying the earnest delight of a naturalized American mesmerized by national myths, living the dream.

The view from the gallery

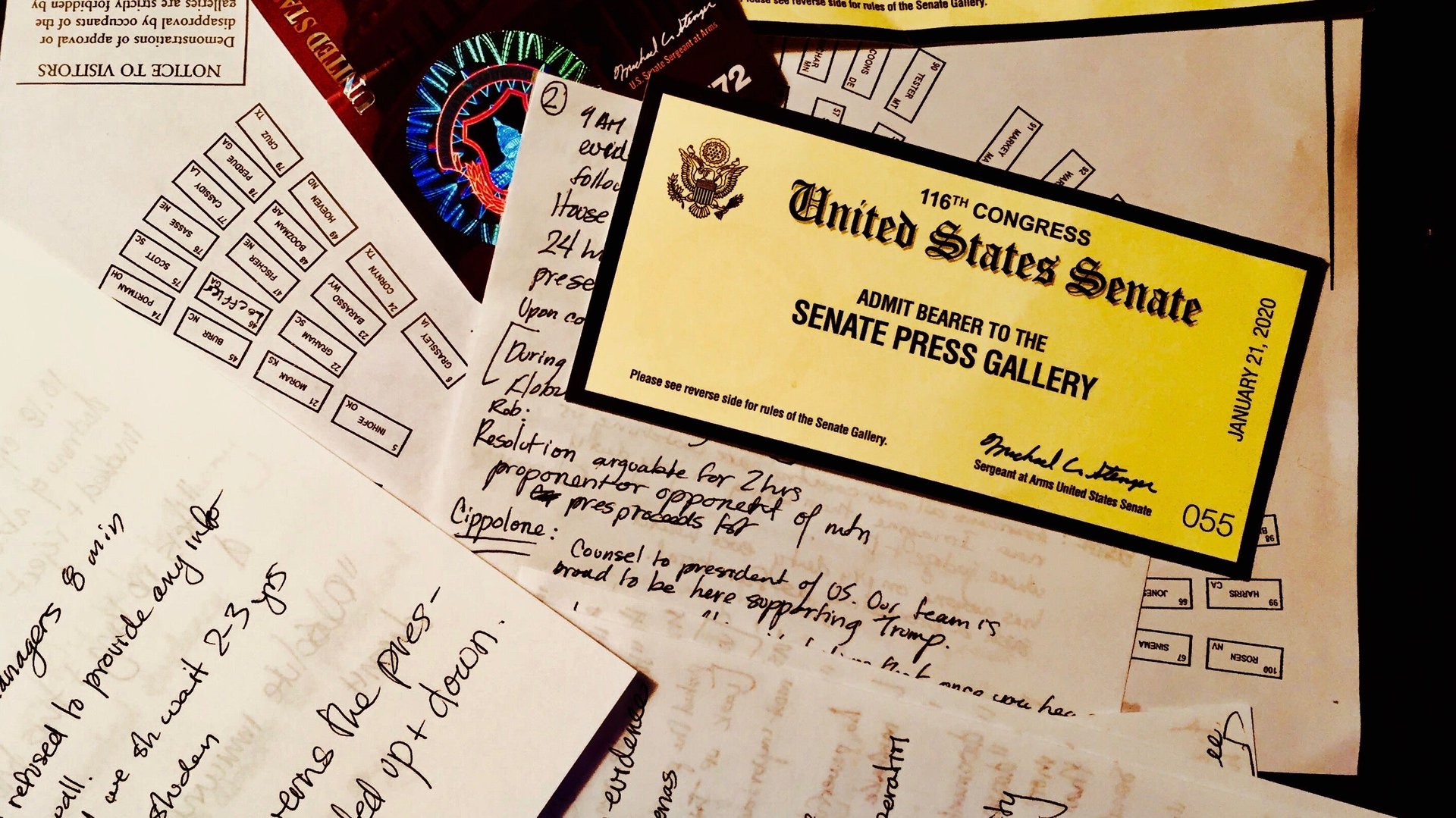

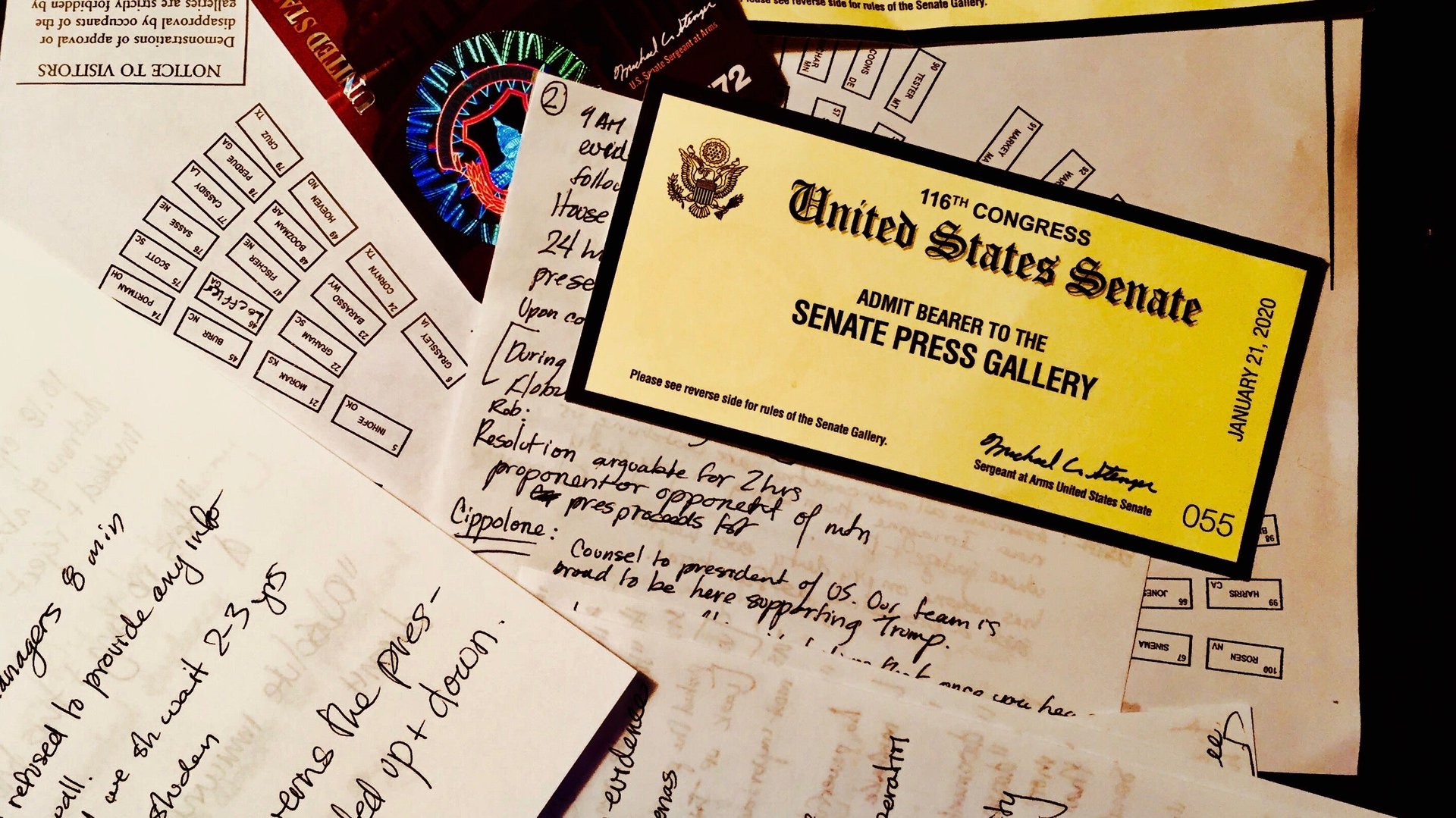

Reporting restrictions during the impeachment trial are circumscribing coverage, however. Only accredited journalists are admitted past security into the Senate chamber, and only if seating was previously secured. Even they are equipped solely with pens, paper, limited passes, and a printed layout of the senators’ seats.

Thus, many reporters are turned away. They can watch the broadcast, but cameras are limited too, restricting the public’s view.

Minority leader Chuck Schumer on Tuesday voiced his concern about the rules on the Senate floor, and other Democratic senators have called the limits “draconian.” The Senate Standing Committee of Correspondents on Jan. 14 sent McConnell a letter (pdf) with concerns and tried to push back on the restrictions ahead of trial, but failed to make headway, to the consternation of numerous publications, civil society organizations, and free press defenders.

Reporters who gain entrance to the Senate chamber can’t post real-time observations for wont of postmodern technology, which seems extra strange for a trial of the tweeter-in-chief. The journalists’ view is mostly of senators, not the prosecution, defense, or presiding Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts, so that’s a lot of telling content about government culture lost.

But here’s what I, and others inside, saw.

It turns out that clerks deliver water and milk to senators, yet all other drink and food is barred (a rule the lawmakers break by, among other things, sneaking peanuts in suit pockets and candy in drawers).

The lengthy proceedings offer a chance to observe Democratic presidential candidates when they’re not expecting to be the center of attention, too. It seems Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar is on high alert for future female president mentions, her expression dramatically shifting when House trial manager Adam Schiff finally referred to tomorrow’s commanders-in-chief as “him or her” in opening arguments. Vermont’s Bernie Sanders sighs incessantly and audibly and slumps uncomfortably, signaling perhaps an impatience or malaise that may not be great in a commander-in-chief, while Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts is keeping cool or nursing a toothache by holding a glass of water up to her face, which might be a sign of laudable resourcefulness either way.

Also noted. Members of this impeachment jury can casually chat with defense lawyers during trial breaks, like senator Pat Roberts of Kansas backslapping Cipollone supportively in stark opposition to legal norms calling for impartial jurors.

If only journalists could enjoy similar intimacy! Those without gallery passes hang around corralled in a designated area, barraging passing politicians with queries, resembling pleading prisoners more than members of the free press of the nation president Ronald Reagan famously called a “shining city upon a hill.”

Given the many press restrictions, after the presidential defense team stepped out of the elevator, reporters shocked by the accidental encounter immediately regretted letting the lawyers get away. “We should have asked something,” one grizzled and exhausted-looking cameraman muttered to his equally fatigued colleague.

“I can’t think fast enough at this point,” the reporter replied.

Arguably, that dullness is by design, a strategic use of scheduling and censorship-lite by McConnell that attempts to make the process more painful than illuminating for all involved, and to stop the public from keeping up.

Patricia Gallagher Newberry, president of the Society of Professional Journalists, argues that restrictions on the press are “a gross injustice to the American people.” She explained, “The press is charged with holding the government accountable. It is through its access that the public is informed. When the public is informed, it can make better decisions. The American public should also be outraged about these restrictions.”

Strategic sleep deprivation

Senatorial wrangling over procedure had gone on until 2am, and some—like chief justice Roberts and writers covering both impeachment and the high court—were running on fumes, rushed meals, and almost no sleep. That I’d failed to pepper the defense with questions in the elevator was perhaps excusable. At least that’s what I told myself while harboring the same regrets and complaints as the cameraman and his colleague.

Maybe it was not much of a lost opportunity, though, given Trump’s defenders have taken a right to reticence in the face of prosecution to astounding levels of noncooperation—even unconstitutional levels, as alleges the article of impeachment for obstruction of Congress.

Trump blocked cooperation in the House inquiry. Now, his lawyers, with McConnell’s aid, are making this trial tortuous and confusing by forcing everyone involved to deal with strange hours and circular claims. They have continually argued that Trump was robbed of due process after refusing invitations to participate in the prior proceedings, which were in accord with House rules. Pointing to the void created by that lack of cooperation and other efforts to thwart the investigation, they say there is no case against the president, thus justifying their adamant efforts to continue blocking witnesses and documents from entering into the trial record.

This approach to matters of historic proportion should worry everyone. As Klobuchar reminded the twitterverse and fellow representatives, “Senators don’t serve at the pleasure of the president.”

🤷🏿♂️ The American experiment 🤷🏽

With all the talk of shams and mockeries and the trial’s outcome assumed, it’s easy to be cynical. But that’s only if you’ve lost all hope in the vision articulated in the Constitution, that notion of a “shining city upon a hill.”

Of course, these are just ideals and in no way reflect the full, brutal realities of the US past or present. But for as long as humanly possible, we must operate in good faith, using them to elevate us above the fray, especially when it counts, like on this historic occasion. Because if we don’t even try to live up to ideals, we won’t come close to achieving them.

Senators must live up to the promise this republic represents to so many because that is the job they were elected to do. If the evidence shows Trump didn’t abuse his power or try to cover corruption, they should acquit. If not, they should vote for removal. Either way, examining the full case is the work.

This impeachment process exists for the people’s protection, as founding father Alexander Hamilton explained in 1788. If this trial ultimately exonerates the president, it should not just be because politicians refused to even feign living up to the Constitution’s ideals.

We, the people, are depending on it. And we’re not at all indifferent. Some of the Senate protestors traveled long distances at great expense to register their dissent. They expect Republicans and Democrats, senators and the president, to uphold the Constitution. They’ll remember everything—or so they vowed to me—when the dust settles.

Same goes for the many who had to work instead. I know because when I flashed my passes in a neighborhood corner store southeast of Capitol Hill on the way home from the trial, the response was universal joy from all, including the clerk and a diverse smattering of a dozen distinctly accented folks who appeared to be of different classes and ethnic origins. For a few minutes we lived the dream. Equal. United in our sense of investment in the American experiment, our shared ownership of, and interest in, US government.

“That’s the ticket!” The man behind me exclaimed, taking a picture to show colleagues at Union Station where he’s worked for 13 years. “Now, this is something to talk about!”

Everyone gushed. Here was documentary evidence of impeachment proceedings! The process matters, as demonstrated by outsized interest in the ticket. Seeing an actual thing, a record, made it all more real and believable, just as admitting witnesses and more documents would do for the trial itself.

We’re not all cynics. Even if some representatives seem jaded, none should ignore the importance of at least putting on a good show. Senators who won’t consider the full case against the president will succeed only in ensuring the world increasingly looks elsewhere for its ideal shining city.