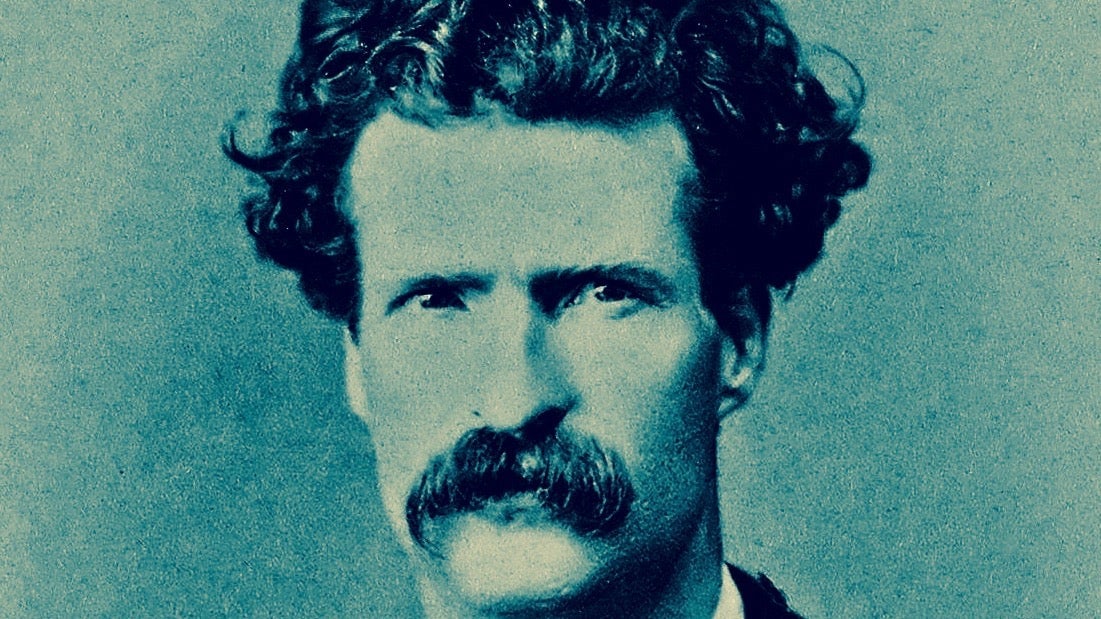

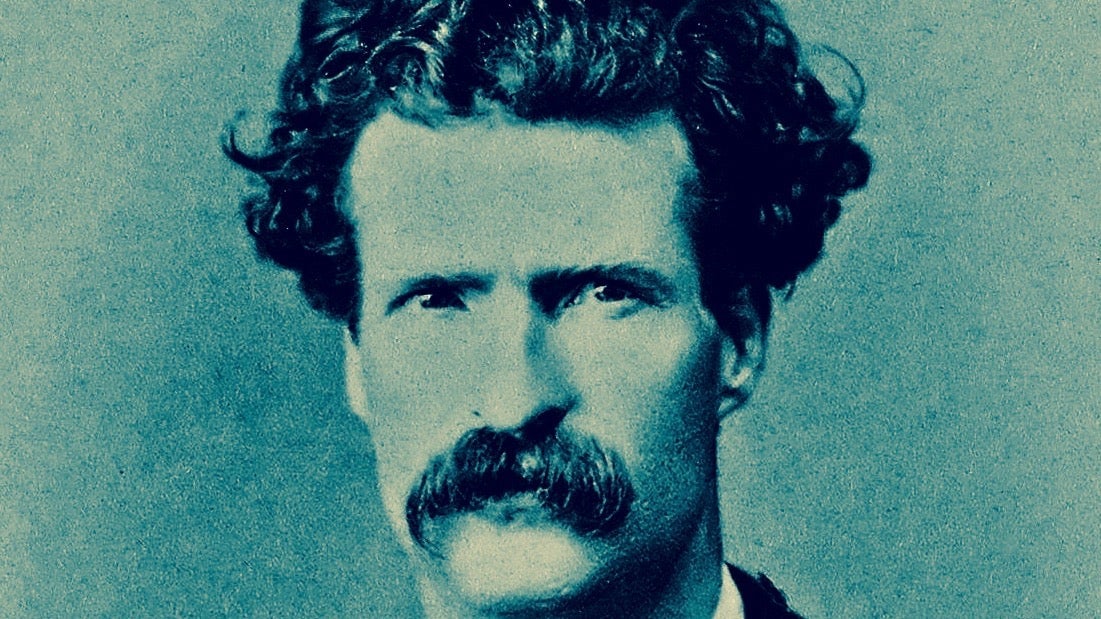

Mark Twain’s 1868 presidential impeachment takes read like today’s news

“I believe the Prince of Darkness could start a branch of hell in the District of Columbia (if he has not already done it), and carry it on unimpeached by the Congress of the United States, even though the Constitution were bristling with articles forbidding hells in this country,” Mark Twain wrote in 1868 about the first-ever presidential impeachment of Andrew Johnson, commander-in-chief #17.

“I believe the Prince of Darkness could start a branch of hell in the District of Columbia (if he has not already done it), and carry it on unimpeached by the Congress of the United States, even though the Constitution were bristling with articles forbidding hells in this country,” Mark Twain wrote in 1868 about the first-ever presidential impeachment of Andrew Johnson, commander-in-chief #17.

The sentence could arguably have been penned today, and reading Twain is a helpful reminder that there really is nothing new under the sun or in American politics.

Just like on a historic winter weekend past, American lawmakers will spend this Saturday considering impeachment. President Donald Trump’s lawyers will make opening statements in the Senate trial, arguing that commander-in-chief #45 committed no impeachable offenses and accusing Democrats of turning policy disputes into constitutional violations, claims that mirror Twain’s complaints about “Radical Republicans” of yore.

A literary impeachment history

Twain came to work in Washington, DC in November 1867, just before Johnson’s impeachment trial. He complained about local atmospheric conditions, writing:

There is too much weather … It is tricky, it is changeable, it is to the last degree unreliable. It has catered for a political atmosphere so long that it has come at last to be thoroughly imbued with the political nature … if the President is quiet, the sun comes out; if he touches the tender gold market, it turns up cold and freezes out the speculators; if he hints at foreign troubles, it hails; if he threatens Congress, it thunders; if treason and impeachment are broached, lo, there is an earthquake!

The correspondent quickly landed a congressional side hustle for extra cash, a common practice back then. Twain visited Nevada senator William Stewart wearing a battered hat, with “an evil-smelling cigar protrud[ing] from the corner of his mouth,” the politician recalled. Despite this “sinister appearance,” Stewart hired Twain as his secretary, and the aspiring novelist returned the favor by forging the senator’s signature, responding to constituent complaints with literary-style admonitions, and rejecting a Treasury Department report because “there were no descriptive passages in it, no poetry, no sentiment—no heroes, no plot, no pictures—not even wood-cuts.”

By contrast, Twain’s political pieces had all that (minus the wood-cuts). He penned a satire featuring himself as the hero in a rollicking fake news account mocking calls for president Johnson’s impeachment. In it, Twain, as “Doorkeeper of the Senate,” charges chamber entrance fees, votes on both sides of motions, and interrupts scheduled discussions to talk female suffrage by “always commencing with the same tiresome formula of ‘Woman! Oh, woman.'”

The “grand tableaux” concludes with two Judiciary Committee impeachment reports about these alleged constitutional infractions. However, the allegations levied against Johnson weren’t as laughable as the humorist’s fictional account.

Johnson had been Republican president Abraham Lincoln’s vice president, a Democrat from Tennessee who served as VP for only 42 days before Lincoln’s 1865 assassination. The southerner’s conciliatory approach to states threatening secession after the civil war angered “Radical Republicans.” They blamed Johnson’s leniency for the Black Codes, which denied freed slaves their civil rights, that Confederate states imposed once back in the union’s fold.

Battle wounds were fresh and Johnson’s presidency was stormy. After attempting to dismiss war secretary Edward Stanton without congressional approval in violation of the Office of Tenure Act that the president had vetoed, Radical Republicans in 1867 moved for impeachment.

As Trump supporters now complain, it was not the first time the president’s opposition called for his removal. Like some today, Twain believed the prosecution stemmed from a kind of “deep state” conspiracy in a government “filled with radicals who have openly clamored for the impeachment of the President.” Indeed, the 19th-century writer at times sounded starkly like team Trump.

Take the recording ABC News reported on yesterday, related to the president’s allegedly corrupt Ukraine dealings. It seems to reveal two former business associates of Trump personal attorney Rudy Giuliani last year complaining that longtime State Department employee, US ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch, was badmouthing Trump and predicting impeachment, to which the president apparently responded, “Get her out tomorrow. Take her out. OK? Do it.”

Yovanovitch was eventually recalled. Trump has denied association with his lawyer’s people. But he admits he was never a “fan” of the ambassador, defending his decision to remove her as presidential prerogative and not part of any corrupt scheme.

Or as Twain once put it, “A Cabinet may dispense patronage. The one we have at Washington does this on a small scale, but more to the President’s injury than benefit. Nearly all the government employés are in sympathy with Congress, supply[ing] aid and comfort to the radicals.”

History and repetition

The “radicals” past made headway. As Twain wrote, “And out of the midst of the political gloom, impeachment, that dead corpse, rose up and walked forth again!”

Twain’s zombie is back now, and if Johnson’s historic trial is any indication, Trump will be acquitted. The 17th president narrowly avoided conviction after a long, bifurcated Senate trial that concluded in late spring.

Twain predicted this outcome by early April, having watched impeachment excitement fade, only to be subsumed by cynical political calculations. He accused impeaching Republicans of a disconcerting “disposition to drop the high moral ground,” fearful of retaliation upon recapture of the presidency.

But he spared no one his scorn. “The Democrats do not howl about impeachment much now, a fact that awakens suspicion. Maybe they are satisfied that to martyr the President would make a vast amount of Democratic capital for the next election,” Twain wrote.

His analysis still works. A presidential election is looming and both parties will be considering the consequences of this impeachment in that light. Concerns about coming payback may convince Democrats to strategically chill. Republicans have compared Trump’s martyrdom to Jesus’s plight, hoping a failed attempt will help him win four more years in November.

Time will tell just how much history repeats. But it’s notable that the Democrat Johnson lost his post-trial election to a “Radical Republican.”

In the end, however, Twain condemned both parties for placing politics above principles, putting all jokes aside and writing, “This everlasting compelling of honesty, morality, justice and the law to bend the knee to policy, is the rottenest thing in a republican form of government. It is cowardly, degraded and mischievous; and in its own good time it will bring destruction upon this broad-shouldered fabric of ours.”