Amazon summed up its hopes for its international sales years ago, in a line buried in its annual reports to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. “We expect that, over time, our International segment will represent 50% or more of our consolidated net sales,” it said in its filing for the 2005 financial year.

The line appeared in every annual filing through its 2013 financial year, after which it disappeared, apparently along with Amazon’s belief that international sales could be half its business or more.

Since 2010, Amazon’s overseas business—currently about 27% of its total sales—has failed to grow as quickly as its domestic one. In 2019 it slowed further, with sales growing about 13% versus 21% the previous year. Of course the US is one of the biggest retail prizes in the world, and Amazon is in an enviable position when its biggest business is its fastest growing. But overall it has struggled to duplicate its US results overseas despite years of work and investment. For now at least, it remains one of the few areas where Amazon has fallen short of its outsized ambitions.

The company’s first major defeat came last year, when Amazon finally gave in and closed its domestic Chinese business. It had entered the country in 2004 with a roughly $75 million purchase of Joyo, an online book seller. It spent the following years investing to build it into a bigger e-commerce portal, eventually rebranding the company Amazon China. But by 2014 Amazon’s shareholders were growing frustrated (paywall) as it continued to spend in China with little to show for it. Amazon was unable to lure shoppers away from the country’s homegrown e-commerce giants like Alibaba and JD.com, and never owned more than a small sliver of the market.

In Brazil, another important e-commerce market, the company has met resistance too. Since launching there in 2012, it has failed to gain much ground against the country’s entrenched e-commerce leaders, such as Argentina-based MercadoLibre, which offer Brazil’s shoppers a better selection and have more developed delivery networks.

Elsewhere Amazon has fared better, but not without significant challenges. The company has invested billions in projects such as expanding its fulfillment network and taking over warehouses across Europe. In the UK and Germany, its business has thrived, but in categories such as apparel, it hasn’t been able to gain the same grip on the European market it has in the US. European regulators have also raised antitrust concerns over Amazon being both a retailer and a marketplace. Germany launched an investigation into the question in 2018, Italy opened its own in April 2019, and the European Commission began an antitrust probe of Amazon a few months later. The outcomes could potentially affect its future in the region.

In Japan and Mexico, meanwhile, Amazon has managed to gain a foothold, despite the competition from rivals such as Japan’s Rakuten and MercadoLibre again in Mexico. In recent years, it has also started selling in places such as Australia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore as it keeps at its global expansion. And one market the company seems particularly intent on is India.

Within a few years of its 2013 launch in India, Amazon raised its planned investment in the country to $5 billion. But while it has grown into one of the country’s big online retailers, its spending has yet to yield big dividends. In its annual filings, Amazon only breaks out separately countries that “represent a significant portion” of its total sales and India has never been among them. It’s also now engaged in a costly fight against Walmart, which bought India’s homegrown e-commerce site Flipkart in 2018.

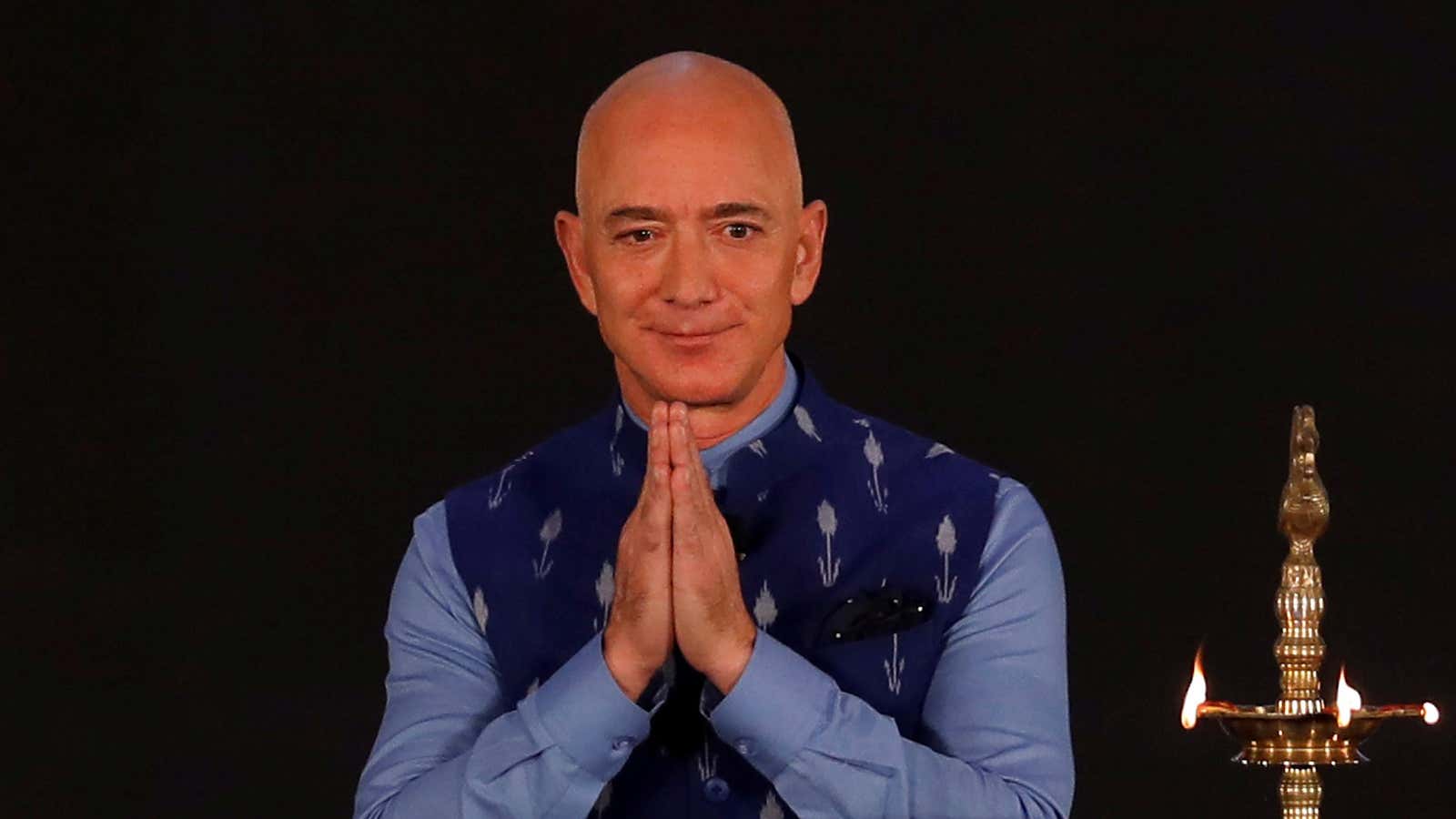

Still, it isn’t giving up. On Jan. 15, Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO, joined the company’s India head, Amit Agarwal, at an event in Delhi. Wearing an indigo Nehru jacket over a pale blue shirt, Bezos pitched the country’s small- and medium-sized businesses on selling on its local platform. His hope, he said, was for India’s sellers to export $10 billion worth of Indian-made products with Amazon’s assistance by 2025. He also pledged $1 billion in investments to help bring 10 million Indian vendors online.

But his trip met with a chilly reception from protesters accusing Amazon of predatory pricing, and from India’s government, which has cast a wary eye toward Amazon and Walmart. At about the same time Bezos arrived in India, the country’s antitrust regulator started a formal inquiry into Amazon and Flipkart, and during his visit prime minister Narendra Modi reportedly refused to meet with him.

Amazon has a reputation for being patient and playing the long game. It may yet find ways to supercharge its growth overseas. It could still make a move in China, for instance, by merging its business there with a local company, such as NetEase’s shopping site Kaola, though it’s unlikely to take much share from Alibaba at this point. And India’s e-commerce market is still growing rapidly, allowing Amazon time to make its mark. But it won’t happen easily, and the present reach of its overseas business still has yet to match its early ambitions.