Impeachment trial finale: “The president’s defense was a fiction”

The historic, third-ever presidential impeachment trial in the US Senate ended today like the two that preceded it in centuries past. The accused was acquitted—in this case, just as everyone predicted he’d be.

The historic, third-ever presidential impeachment trial in the US Senate ended today like the two that preceded it in centuries past. The accused was acquitted—in this case, just as everyone predicted he’d be.

A majority of Republican senators found Donald Trump not guilty of abuse of power, with the exception of Utah’s Mitt Romney. None of them found he obstructed Congress. Meanwhile 47 Democratic senators, including the few potential party line defectors, found the president guilty on both articles of impeachment.

After the votes were tallied, the presiding magistrate, Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts, directed the judgment be entered into the record, declaring Trump “hereby acquitted.”

The outcome wasn’t a surprise. Yet the acquittal will do little to convince some of the people, or Democratic lawmakers, that Trump is innocent, especially in light of information that the House inquiry and reporting about his Ukraine dealings brought out.

There is reason to believe that the president conditioned congressionally-approved military aid on a foreign nation initiating an investigation into his personal political rival, jeopardizing the integrity of US elections. But the Senate trial was a truncated political process—not like a trial in a court of law—and included no witnesses or documentary evidence.

Trump and his defenders contend, instead, that the president was concerned about corruption in Ukraine and European burden-sharing for aid. They say that based on the House impeachment inquiry record alone, it’s clear the president was acting in the national interest when he asked Ukraine’s president for “a favor.”

Oregon senator Ron Wyden, for one, wasn’t buying it. “The president’s defense was a fiction,” the Democratic lawmaker told Quartz as he emerged outdoors after the trial into a gray and cold afternoon, the front lawn of the Capitol filled with chanting protesters holding signs while police patrolled the paths. “The president was causing corruption in Ukraine rather than rooting it out.”

We, the people

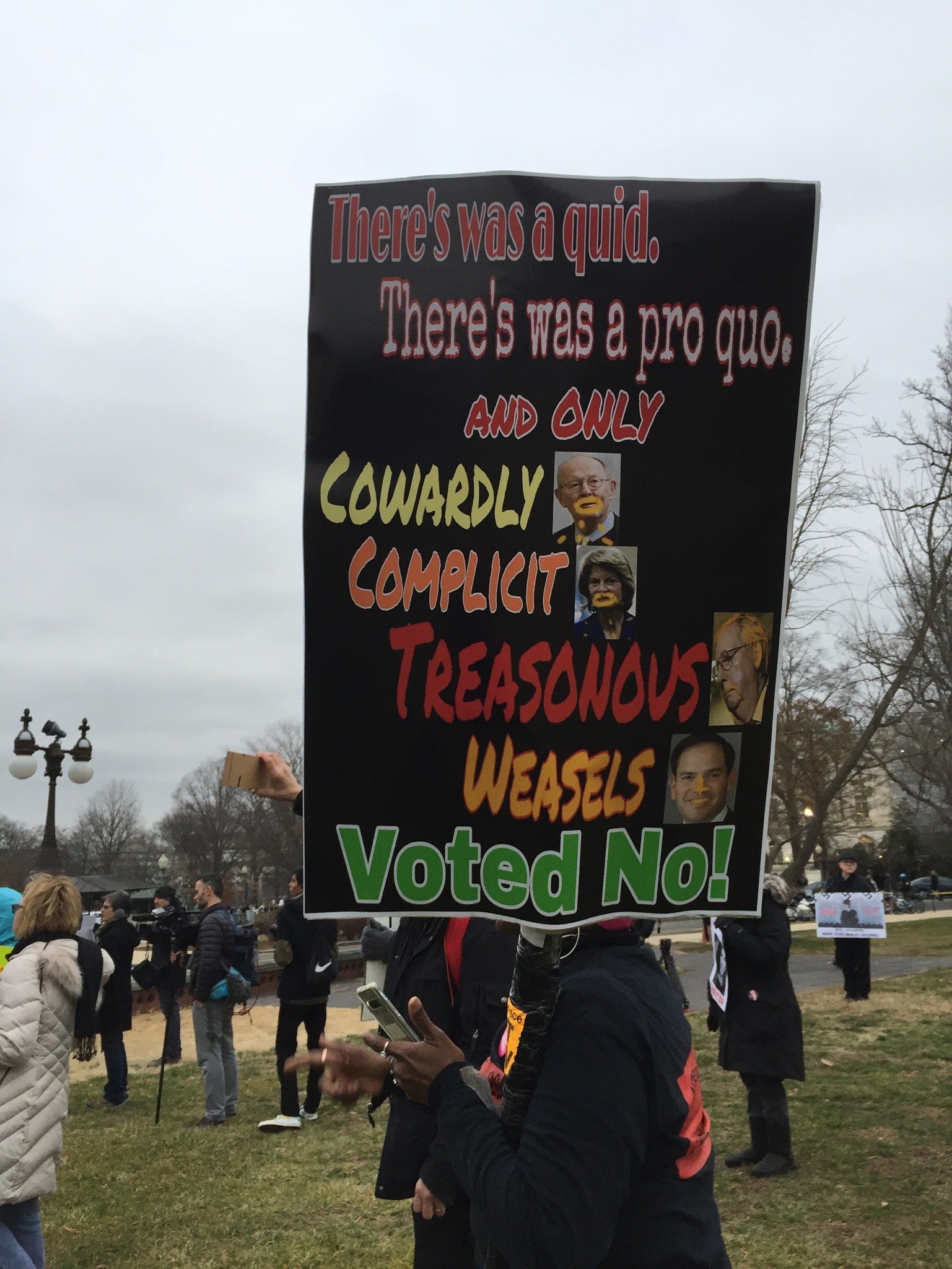

Some of the people, at least those holding messages and chanting, certainly seemed to agree. With their backs to the high court and placards facing emerging lawmakers, they called out senators who voted against hearing from witnesses with direct knowledge of the president’s actions, calling them cowards and much worse.

The protesters said the trial was a “coverup” and warned that history would not remember these politicians kindly.

It was pretty much the same message minority leader Charles Schumer sent when he gave his concluding remarks to a mostly-empty Senate chamber just before the final votes were taken. “A trial is a place where you seek truth,” the longtime senator from New York said. “Our nation was founded on truth. But there was no truth here.”

He accused Republicans of walking the halls of government with their heads down, ignoring the fact that Trump is “a menace, so contemptuous of every virtue that you have to ignore the truth” to support him. “You cannot be on the side of this president and be on the side of truth.”

Schumer urged Americans not to lose hope, though the Senate trial may have caused them to doubt the soundness of the founding fathers’ approach to the separation of powers.

Yet, when he was done talking and forced to listen to majority leader Mitch McConnell’s parting shots, he slumped, angry and defeated. Even the senator’s sartorial style said he wasn’t feeling playful anymore—gone were the bright ties and wry smiles of days past. He wore a muted blue-gray suit and tie and an unusually grave countenance.

The flip side

McConnell’s message was brief and acrimonious though he called for peace. He basically said the Democrats were sore losers unable to accept the fact that they can’t nab the presidency, then accused them of election interference, thus impeaching the impeachment.

“Normally when a party loses an election, it accepts defeat. Not this one,” he explained. “They still don’t accept voters’ decisions and are preparing not to accept the next one.”

The majority leader’s hope, or so he said, was that the impeachment trial’s end would break the “factional fever” that had overtaken lawmakers and the nation. It was either wishful thinking or purely rhetorical as he certainly made no effort to be conciliatory with Democrats, and to lead by example.

Instead he cited a litany of Democratic offenses, including “the far left [trying] to impugn the chief justice for staying neutral” at the trial. From McConnell’s perspective, only Republicans remember how to have a proper policy debate “within traditions,” while Democrats “declare a war on traditions themselves.”

“I hope we’ll look back at this day and say this was the day the fever began breaking,” the majority leader concluded. “I hope we will not say it was just the beginning.”

The end has no end

As ever, the two sides seemed to be speaking the same language—American English peppered with references to the Constitution and its framers. But the fever is apparently impacting Americans’ ability to hear one another.

Democrats and Republicans interpret the same words, ideas, and information utterly differently and reach entirely distinct conclusions, making McConnell’s supposed hopes about “the institutions breaking the factional fever rather than the other way around” seem like an impossible dream at this point.

Inside the Senate chamber, displays of emotion about the votes are barred. Only from a slump, smile, handshake or gleam in the eye can you know who is down and who’s triumphant.

But if McConnell has glanced at protesters’ signs, then the Republican surely knows that some Americans believe that he and the Grand Old Party sold their souls, betraying their constitutional oaths when they put fealty to the president above all else.

As one placard bearing an image of McConnell’s face put it: “There was a quid. There was a pro quo. And only cowardly, complicit, treasonous weasels, voted No!”