For a sign of how much coronavirus and a Chinese slowdown could hurt Latin America, take a look at Chile, which sells about a third of its exports to China.

Chilean officials are now hastily trying to offload shipments of wine, cherries, and seafood elsewhere in Asia, according to Bloomberg, after Chinese purchases fell between 50% and 60% since the coronavirus outbreak first began. Amid Chinese port shutdowns, large cargos of copper, of which Chile is the world’s largest producer, linger onshore. Copper prices are only just recovering from a 14-day tumble tied to the crisis.

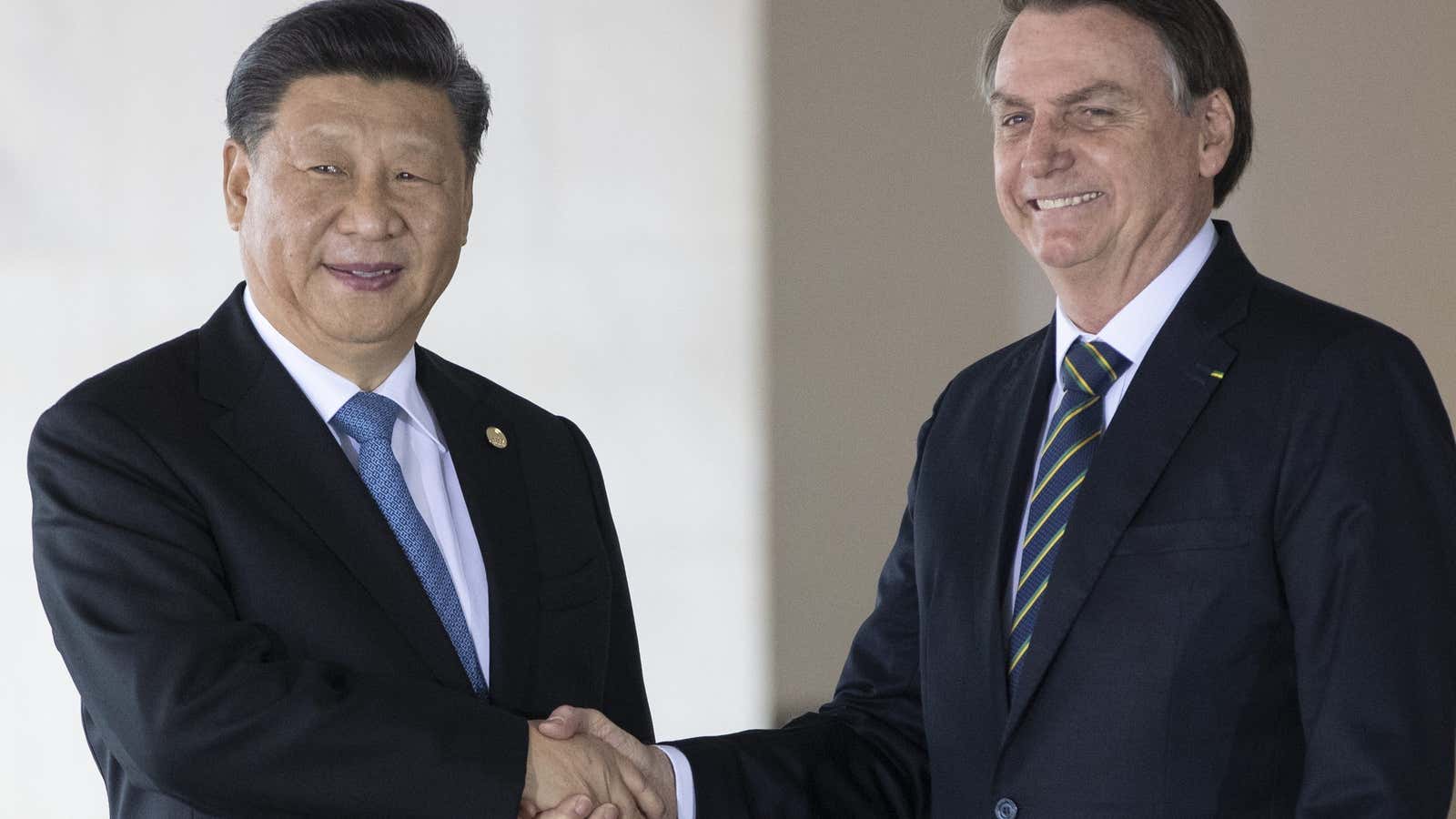

In the past decade, China has gone from playing a moderate role in Latin American trade to becoming the region’s second-largest trading partner. It is now the top importer of goods from Brazil, Peru, Uruguay, and Chile.

A poor first quarter for China would prove an inauspicious start to the decade for Latin America, after its “lost decade” of the 2010s ended with a year of violence and instability across the region. As a result of the virus, UBS has already slashed its growth forecast for Brazil, the region’s biggest economy, from 2.5% to 2.1%, a UBS representative told Quartz.

“Latin America, in terms of regional growth, had the lowest of all the regions in the world in last year,” said Pepe Zhang, who leads China-Latin America research at the Atlantic Council, a think tank. “In this context we also have the coronavirus situation, so it seems like external forces are not exactly favorable.”

A Chinese slowdown could hit the region in a number of ways, said Andres Abadia, senior economist for Latin America at Pantheon Macroeconomics, a research firm. “We have to expect a big hit to Chinese demand for Latin American goods, particularly commodity prices, and disruption to China-based supply chains for a couple of months, at least, so we await the next round of business surveys from [these] countries with a degree of trepidation,” he wrote in an email to Quartz.

Abadia highlighted Chile and Peru’s dependence on commodity exports to China as a particular weakness, adding that Brazil and Mexico could be hit both by lower commodity prices and slower manufacturing globally.

A big risk for Latin America is that China’s first quarter results could turn out to be a write-off, which “would hit already weakened business sentiment,” Abadia wrote.

Investors showed their leeriness about putting money into Latin America while China is floundering as soon as the coronavirus sparked turbulence in global markets in late January. Latin American indexes suffered greater blows than many counterparts in Europe, the US, and Japan, before recovering somewhat when China announced a stimulus package and researchers claimed some success in treating the virus.

The initial selloffs were driven mainly by an urge to move out of risky environments, bolstered by falling commodity prices and fears about Latin America’s exposure to China, said Ernesto Revilla, head of Latin America economic research at Citigroup.

Kickstarting much-needed growth in the region will be tough, experts said. “Latin America is in a difficult spot where it’s not obvious where to find a new model for growth—and investment is very weak in the region,” Revilla said. “China is playing an important role in many countries in Latin America, but a slowdown in China will decrease the level of investment from China to these Latin American countries.”

To drive growth beyond the near term, Latin American governments have to boost spending on infrastructure and make reforms in areas like labor markets, ease of doing business, and in diversifying away from commodities, Abadia said.