When Donald Trump jumped into the 2016 presidential election, conventional wisdom assumed that the “billionaire” would attempt to buy the election with his riches.

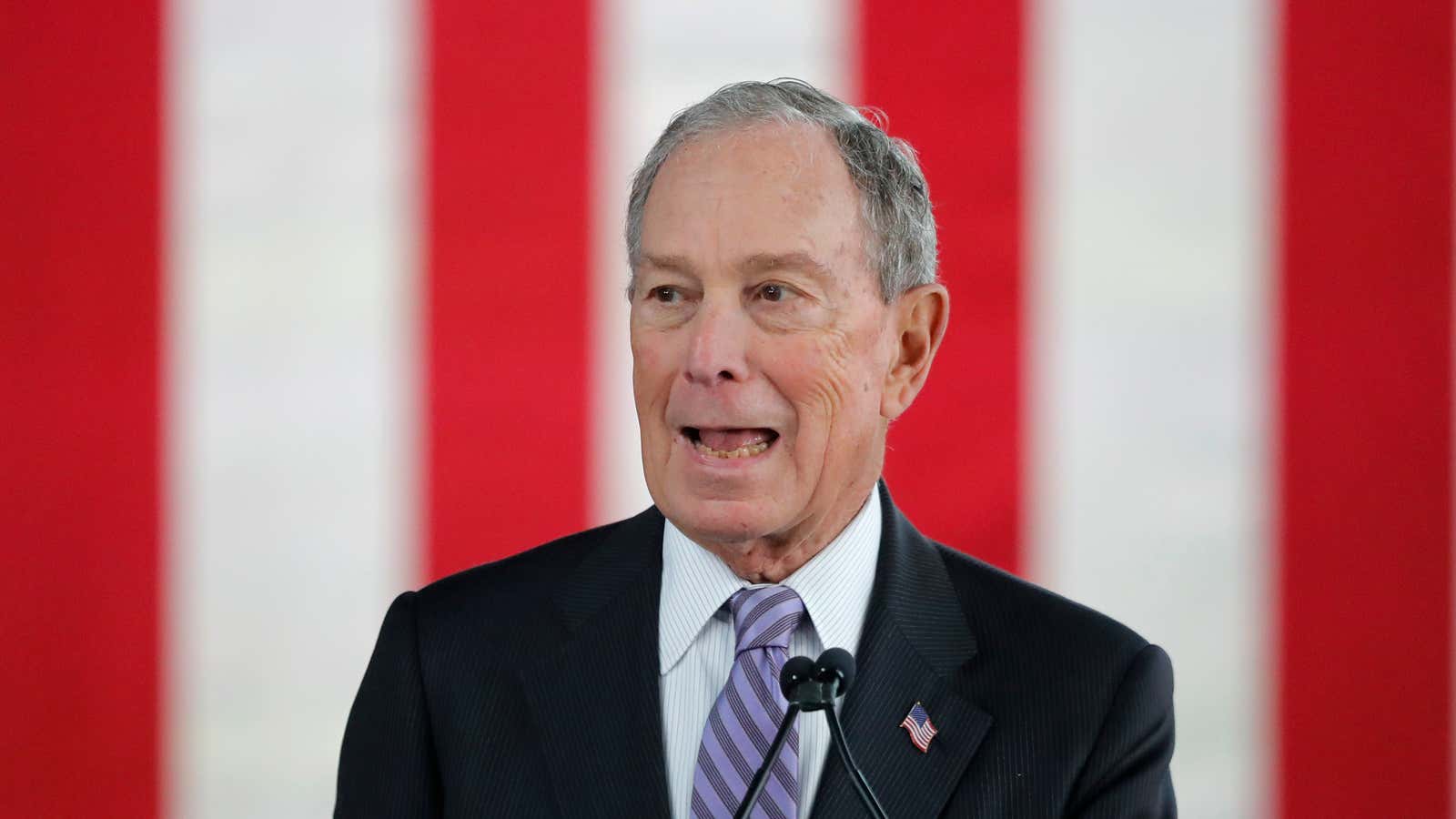

That didn’t happen. But former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, whose estimated net worth of $61 billion would make him the 12th richest person on his eponymous financial data company’s global rankings, is throwing cash into his campaign at a rate never before seen.

In 2016, Trump spent far less than his general election opponent, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, and he didn’t contribute much of his own money to the campaign. During the 21 months he officially contested the 2016 election, primary and general, Trump spent $325 million, contributing one-fifth of the total himself.

In the first two months of his primary campaign, till the end of December, Bloomberg spent $188 million, and all of it came out of his own pocket. That means he’d already spent, personally, more than twice as much as Trump did.

The flood of money is even making Tom Steyer, the liberal hedge fund manager running on a platform of combatting climate change, look like a spendthrift. Steyer has spent about $200 million, but has done so at a much slower rate, over six months. (Trump has yet to put any of his own money into his reelection campaign, and spending will be split with the Republican National Committee and a fundraising entity called the Trump Make America Great Again Committee.)

In particular, Bloomberg is pouring money not just into TV and online ads, but into a massive staff of political operatives working to get out the vote. His hiring of field organizers at unheard-of rates of $6,000 per month even has Democrats in lower-tier races complaining about a lack of campaign labor.

And that doesn’t include previous civic-minded spending that is now being paid back in the form of endorsements from elected leaders like Washington, DC mayor Muriel Bowser (Bloomberg awarded her administration a share of a $70 million fund to support climate change initiatives) or California Rep. Harley Rouda (a Bloomberg political action committee backed Rouda’s 2016 campaign with $4.5 million in spending).

While Trump’s image as a man of wealth was key to his message, it was not central to his campaign strategy. He raised money by selling merchandise like the infamous red MAGA hats. And it’s hard to know how much of his campaign spending he’s recouped by paying his own businesses, or since his election, by funneling public money into those businesses and taking advantage of influence-seekers buying rooms at his hotels.

In Bloomberg’s case, signs suggest there is return on his investment so far, at least in terms of name recognition—despite entering the Democratic primary months after his rivals, he’s vaulted into third place, behind the front-runner, senator Bernie Sanders, and former vice president Joe Biden in national polls.

But as Biden’s dismal experiences in the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary election show, national polls aren’t everything. Bloomberg, a former Republican, hasn’t endeared himself to progressive voters in the Democratic party on issues like criminal justice, where he recently disavowed his embrace of police targeting minority youth, or his record of sexist remarks to women and allegations of creating a toxic workplace.

For now, Bloomberg currently sits in fifth place in polls in Nevada, the next state to weigh in on the Democratic primary on Feb. 22. That gives him eight days to gain ground—but his campaign is squarely pointed at the big delegate hauls available on Super Tuesday, March 3, when states like California, Texas, Colorado, Virginia, and North Carolina vote.

Political scientists still debate when and how campaign spending is effective in electing politicians, but this will be a test case for the ages. Bloomberg has said he will keep his campaign going to defeat Trump whether or not he wins the Democratic nomination, likely making 2020 more expensive than the record-setting 2012 election.

What has Bloomberg been spending on? Per the Federal Elections Commission data through the end of 2019, the two biggest costs have been television advertising ($132 million) and digital outreach ($20 million). Some of the costs reflect a late entry to the campaign—buying lists of voters to contact ($3.2 million), hiring people to gather signatures to get his name on the ballot ($373,441), and hiring recruiters to bring onboard staff ($107,000).

Some of the spending reflects Bloomberg’s lavish approach to field campaigning; in its first two months, the organization paid $1.6 million in salaries, purchased more than $1 million worth of computer equipment, more than $250,000 worth of office furniture, and $843,000 worth of promotional materials.

And some of the spending reflects, well, Bloomberg himself: He contributed $50,000 worth of use of his company’s financial data terminals.