On a bitterly cold Wednesday morning in February, the Eastside district of Birmingham is quiet. This newly-renovated area, off the Digbeth Branch Canal, looks and feels expensive. Amid the greenery of Eastside City Park, a grey pathway leads visitors past the Birmingham Science Museum, the Millennium Point Conference Center, and the Parkside and Curzon wings of Birmingham City University.

There’s a certain stillness to this shiny new part of the city, save for a few students walking from building to building, sheltering themselves from the wind, and the steady humdrum of construction. Bright red signs posted at regular intervals inform curious visitors that the work taking place across the Eastside is part of the High-Speed Two (HS2) railway project, a £106 billion ($138 billion) infrastructure project that will connect London to Birmingham at two points—Birmingham Airport and Curzon Street station in central Birmingham—and eventually further north, to Crewe, Manchester, and Leeds.

Birmingham is the second-largest city in Britain and it is Ground Zero for this controversial project, which was launched in 2009 by Gordon Brown’s Labour government. The goal was to convert 46 million domestic travelers from planes to high-speed trains. The first phase of the project, the London-to-Birmingham line, was supposed to be operational by 2020, and cost £7 billion. When prime minister Boris Johnson gave the green light for the project to continue last week, the cost estimates had ballooned to 15 times that amount, with Phase One of the line not expected to be finished until 2028 at the earliest.

Birmingham has a special place in English history and folklore. It sits right by England’s so-called “black country,” an area of the West Midlands that was covered in smoke and soot for much of the 19th century because of heavy industry. Brits’ perceptions of Birmingham are best summarized by Mrs. Elton, a rather obnoxious character in Jane Austen’s 1816 novel “Emma”: “They came from Birmingham, which is not a place to promise much, you know, Mr Weston. One has no great hopes of Birmingham. I always say there is something direful in the sound.”

While poking fun at Birmingham has been a popular British pastime, the city has changed. It has three major soccer teams and a diverse population, with large South Asian and Afro-Caribbean communities, as well as more recent Eastern European migrants. It is considered the home of heavy metal, too, and Shakespeare and Tolkein were born nearby. It has always been an engineering hub: The original, iconic Mini rolled off a Birmingham production line in 1959. And the city is undergoing an economic revival, driven by its role in some major infrastructure projects across the Midlands, chief of which is HS2.

The major proposition of HS2 is that it will “connect the Midlands and the North much more closely together, it’s going to connect the North to itself, which is really difficult at the moment, and the same with the Midlands, because it’s really hard to get from the East Midlands to the West Midlands,” says James Bovill, media lead for Midlands Connect, the transport body for the region. Currently, the north of England, the East Midlands, Scotland, and Wales are some of the worst-connected regions in the country. The quality of the existing rail networks in these areas is also very poor.

As the first major city on the new route, Birmingham stands to benefit from the renewed investment and focus on the Midlands that HS2 has promised to deliver. But people who live there are not sure that a single infrastructure project, no matter how ambitious, can “heal the North-South divide,” as former deputy prime minister Nick Clegg argued in 2013.

What are the benefits of HS2?

In the mornings, a train leaves London for Birmingham approximately every 15 minutes. The 7:23 am fast train leaves Euston and arrives at New Street station one hour and 22 minutes later, at 8:45 am—this would be shortened to 45 minutes with HS2.

The train is full of commuters and business travelers with a confusing range of opinions about HS2. Most point out that the journey from London to Birmingham is already quite fast. “We have this train, so I question why we need it,” says Ben Brown, who commutes to Birmingham two to three times a week. “It’s not as if the train that we’re in…is particularly slow,” echoes Damon Lacey, a human relations consultant from Portsmouth.

Proponents of HS2 will point out ad nauseam that the point isn’t the journey time; it’s the increased capacity that a new railway will bring, allowing faster trains to shift on to their own track, and rendering the network more efficient. “We’ve been working off Victorian infrastructure on our national rail network and demand is increasing at an unprecedented scale, and we need more capacity,” explains Adam Tyndall, program director for transport at London First, a business advocacy group.

Opponents say the new line will displace hundreds of homeowners and harm the environment, including up to 32 ancient woodlands between London and Birmingham, according to The Woodland Trust. They point to the project’s spiraling costs and question the figures used by the government and by HS2 Ltd., the state-owned company that oversees the project and has been accused of chronic mismanagement and overspending (paywall).

HS2 Ltd. told Quartz in an email that it had put in place schemes to alleviate the impact of construction on homeowners and on the environment, including by purchasing homes located on land needed for the construction and compensating homeowners not directly on HS2’s route whose property value may be negatively affected by the railway. However, the National Audit Office, Britain’s public spending watchdog, reports that, between 2017 and 2018, only half of advance payments (pdf, p.8) for homeowners were completed within the required time.

Regarding concerns about woodlands destruction, HS2 Ltd. said: “There are 52,000 ancient woodland sites in England. Our published assessments are that 62 ancient woodlands will be affected by HS2’s full route. Over 85% of the 62 ancient woodlands will remain intact and untouched by HS2. Where an ancient woodland is described as affected, in many cases this may mean a small section of an overall woodland is affected.” They said that, on the route between London and Birmingham, the total area of loss for 19 of the 32 affected woodlands is less than one hectare.

In Birmingham, critics also say the new station will raise the cost of housing. House prices in the city are up 16% since 2016, according to the housing website Zoopla, and the average property in the city now costs £163,400, while the average full-time worker earned £27,426 before tax last year. Experts say real estate costs will continue to climb as HS2 nears completion and more Londoners choose to settle in Birmingham, pricing out existing residents.

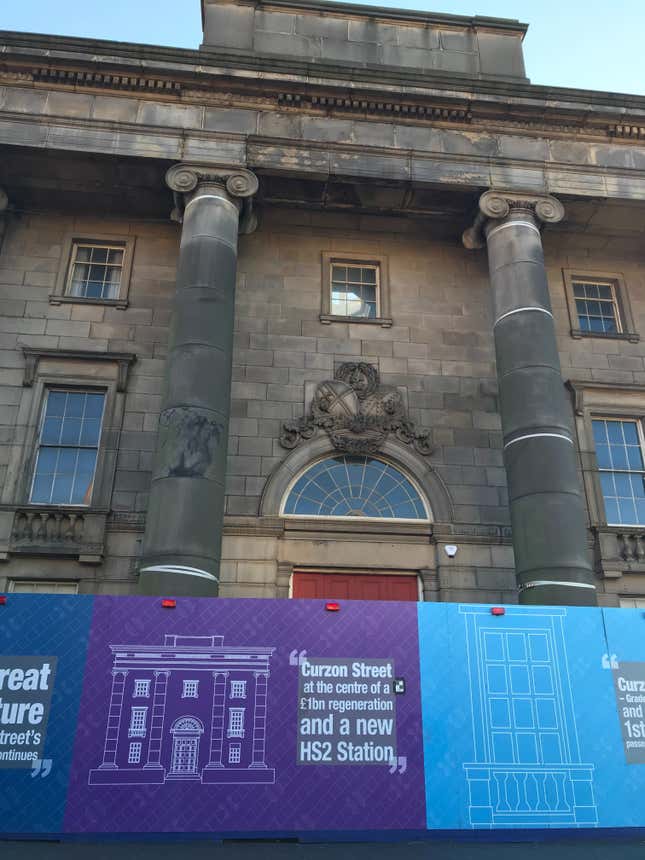

The local government in Birmingham is pitching HS2 as an opportunity for economic revival. Placards that cover the construction site for the new HS2 station feature messages like “Curzon Street at the center of a £1 billion regeneration,” with predictions that HS2 could create up to 100,000 new jobs in the region. But on the city’s streets, it’s not immediately clear that residents are sold on this message, though they seem cautiously optimistic. Russ Hincon lives about four miles from central Birmingham and works at Timpson, a family-run franchise that offers shoe repair and key-cutting services. “Hopefully it brings more people into the city and hopefully more business,” he says of HS2. “It’s good to see Birmingham growing again, because they’ve just left it alone for years and years and years now.”

“I’m not sure it’ll impact my daily life, but I think it’s a good thing to have,” says Nathan, the facilities manager at Carrs Lane Church in the city center. “It’ll bring a lot of income and jobs for the city center, which is needed.” Emma Reynolds manages a Deichmann shoe store on Birmingham high street. She says most of her customers are weekend tourists or locals, not commuters, and she doesn’t think increased railway capacity would affect her business—though she wishes it would. “Hopefully it’ll bring more customers to town, because it is starting to sort of quiet down a little bit.”

There is a lot of anxiety among residents about HS2 Ltd.’s ability to stick to its budget and timeline on the project. “First it’s off, then it’s back on, then it’s off, and then it’s back on again,” complains Hincon.

Those who live in areas outside of the reach of HS2 may feel frustrated. “Quite rightly, people say, well of course you see the benefit, because it’s coming to where you are,” says Laura Shoaf, managing director of Transport for West Midlands. “And I have real sympathy understanding that there are areas for whom HS2 passes through but doesn’t stop, and it’s much more difficult to articulate the benefits to those other bits of the region. But for us, here, there’s a really persuasive argument to be made; it just hasn’t been made yet.”

HS2 Ltd. told Quartz that it had made significant investments in engaging with the people of Birmingham and elsewhere. “Local community engagement managers work on the ground in each community along the route of the railway and have regularly met with local residents to notify them of planned works but also showcase the benefits of Britain’s new high speed railway,” a spokesperson wrote in an email. “Since 2018, we have engaged with over 61,400 people at more than 3,900 events, and answered over 65,000 enquires through our 24-hour Helpdesk.”

And yet, that doesn’t seem to be enough. “If I was going to make a challenge to HS2, I would say that it has been very poorly communicated from the outset,” says Shoaf. “At first, people thought it was about speed, then it became about capacity, and then it’s about regeneration—it’s about all those things. And I don’t think that, to date, the benefits have been clearly articulated.”

Why is HS2 so controversial?

A major argument in favor of HS2 is that it will reduce inequality between London and other major cities like Birmingham, Manchester, and Leeds by better connecting the region to itself and with the rest of the country. Currently, getting from Leicester, in the East Midlands, to Leeds, in West Yorkshire, means driving for 2 hours, or taking two trains with a stop in Sheffield. Once HS2’s East Midlands hub station at Toton is operational, the journey from Leeds to Leicester will be shortened to 45 minutes.

The commuters on the 7:23 am train to New Street are more skeptical of this argument. “I don’t think a single project fixes that [inequality],” says Nigel Thorley, who lives in London and is on his way to a meeting in Birmingham. Several people point to the fact that some estimates show London stands to benefit more from HS2 than the north or the Midlands. “Have you been up north?,” asks Dom Rowles, a consultant in London who is on his way to a business meeting in Coventry. “It’s pretty much a disaster up there. They need so much investment that one line is not gonna fix it.”

“Can one railway station fix some of the disparity of decades of under-investment? No, of course it can’t,” acknowledges Shoaf. “But it’s definitely, I think, a step in the right direction.”

In Birmingham, local authorities like to point out that HS2 has already led to an increase in investment since the project was announced a decade ago. Foreign direct investment (pdf) has increased, with an average annual growth rate of 12% between 2011 and 2017. HSBC moved more than 4,000 jobs to Birmingham since 2014 and invested £200 million in the city, and Deutsche Bank expanded its operation there in 2013. Last month, PwC opened its second-largest UK office in Birmingham, pledging to create 1,000 new jobs by 2021. And two subsidiaries of the luxury real estate company Berkeley Group have committed to invest £300 million to build two mixed-use complexes, including the city’s tallest residential tower.

For Julian Beer, deputy vice chancellor of Birmingham City University (BCU), the future of his school and of HS2 are interlinked. “All around us, we’re seeing quite significant growth and investment in the area, and…that provides us with opportunities for research, for innovation projects, for our students,” he says. BCU is working with HS2 Ltd. and its contractors to find job placements for their architecture, landscape, design, and engineering students. And once Curzon Street station is built, students and staff will be able to benefit from its amenities and the metro extension. “What this has done is made us much more attractive as an institution,” Beer says.

“Birmingham is changing,” argues Shoaf. “I think people genuinely don’t realize how great it is until they get here.” And it’s not just Birmingham, she points out. “There’s definitely a lot more confidence, and some people say, swagger around the region because of the growth that it’s already brought.”

Next steps

Now that HS2 has cleared the major hurdle of government approval, a lot is riding on its success, including the credibility of the Johnson government in the wake of Brexit. But the UK doesn’t have a great track record with “big infrastructure projects and getting them over the line,” admits Midlands Connect’s James Bovill, and “at the moment, people can’t visualize what impact it’s going to have on their daily lives. All they see is a creaking rail network that isn’t providing for them, and they don’t see HS2 as the answer to that.”

Alan, a salesman at Millets Outdoor Store off of Birmingham high street who asked that his last name not be used for this story, is an example of this. He lives in Nuneaton, 25 miles from his place of work, and pays about £11 per day to commute 30 minutes on an overcrowded and often-delayed train. “The train is horrible to be honest,” he says. “Every day, I have to sit on the floor. When I come into work, I’m standing all day, and finish work, and you have to fight into the train, and then you have to stand up somewhere near the tall end in the corner.” He doesn’t think HS2 will change that.

Even in Birmingham, where the benefits of HS2 have already started rolling in, the project is a tough sell. “The thing with HS2 is the budget keeps going up, isn’t it?,” asks Alan. “Maybe by the time HS2 is done, I’m dead.”