Political ads are everywhere, but soon you’ll be seeing them more on maps. An early example cropped up three months ago in Palm Springs, California, where one political group bought ads on the navigation app Waze to direct targeted voters to the polls on a local election day.

Campaign strategists are increasingly looking for new ways to break through the noise, especially as Google has limited micro-targeting on its ad networks and as prices for ads on Facebook have been driven up by record-smashing spending by candidates like billionaire Mike Bloomberg.

And so, more campaigns will likely be turning to Waze.

But don’t worry. If you’re sick of the barrage of attack ads elsewhere, Waze doesn’t allow partisan ads—just those urging people to vote.

Cheryl Hori, founder and chief strategist of progressive digital agency Pacific Campaign House, set up the Waze ad in Palm Springs. Her client, LGBTQ+ advocacy group Equality California, was trying to boost turnout among LGBTQ+ voters and allies in an election for the first city council in America’s to be all-LGBTQ.

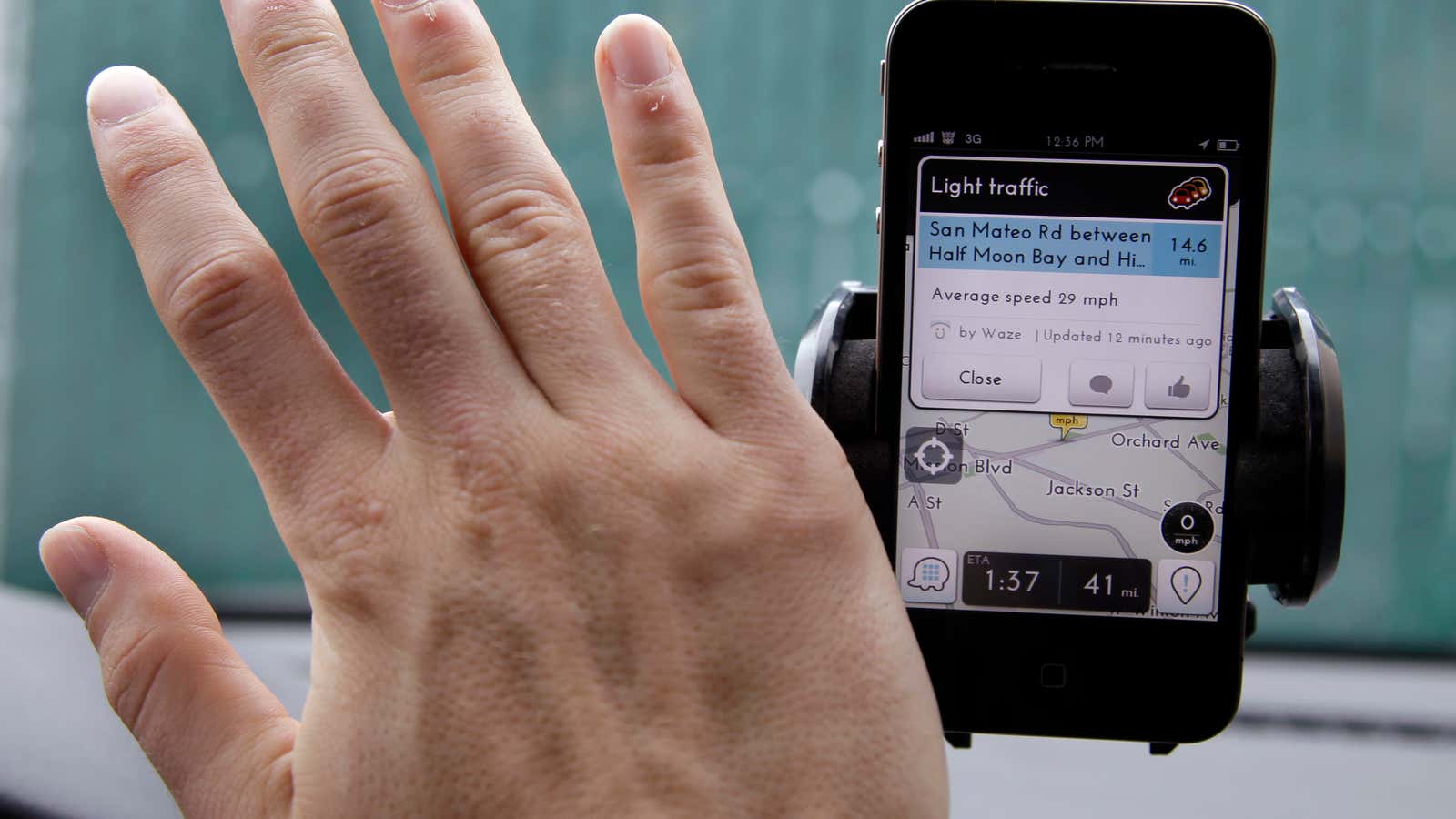

The ad showed up only for people who were driving and using Waze, but who had stopped at a red light. It included a map pin indicating a nearby polling place, Hori said, with the message urging drivers to vote. But the key? “The call to action is a button that says ‘Drive here,’” she noted.

If you click, Waze reroutes you to that polling place. Local businesses have been able to create such ads since 2012. Equality California was the first political group to make one, Hori said.

Waze has 130 million monthly active users worldwide, the company says, but it doesn’t break that out by country.

Waze doesn’t allow micro-targeted political ads on its platform—a rule set even before parent company Google imposed a similar ban more broadly in November 2019. So, Hori noted, the Waze ad tactic would work best in deep-red or deep-blue areas—“a specific neighborhood, pocket, district, wherever it might be that has a very high population of the folks that you’re specifically trying to turn out.”

Since Waze offers no way to advertise to certain voters in particular, there’s no way to guide you to your polling place. The Palm Springs experiment was made easier by that city having only three districts (voters can use any polling place in their district). In other jurisdictions, advertisers might have better luck directing voters to early voting centers, because those tend to serve anyone in the city—but, of course, they are only open before election day.

“For us, it’s about reaching people where they’re at and engaging them to build political power for the LGBTQ+ community and our allies,” said Samuel Garrett-Pate, an Equality California spokesman. He said that the group has also run get-out-the-vote ads on dating app Grindr, where it is currently running ads reminding people to participate in the US Census.

“For us, it’s about reaching people where they’re at and engaging them to build political power for the LGBTQ+ community and our allies,” he said.

In Palm Springs, the cost per voter who clicked the Waze ad was about $5.50, according to Hori. That might sound steep, but it was worth it “to know definitively that you were able to turn somebody out,” she said.

And, her data says, 3% of all voters in that off-year municipal election were turned out via the Waze ad.

Correction: This article originally misstated Equality California’s goal, which was to boost turnout among LGBTQ+ voters and allies in the city council election, not to ensure that every member of the city council continued to be LGBTQ.