What do a satellite company, a rural hospital chain, and an oil driller have in common? They are all considered zombie companies.

For economists, the corporate version of the living dead is a business that’s kept alive by financing instead of by making money. Or, in accountant terms, these are companies that don’t generate enough profit to cover the cost of the interest on their debts.

The zombies’ share of the market appears to be growing. About 17% of the world’s 45,000 public companies covered by FactSet haven’t generated enough earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) to cover interest costs for at least the past three years. Bank for International Settlements economists, using a similar but narrower definition, find that the world’s equity markets’ share of zombies has risen to more than 12%, up more than 8 percentage points since the mid 1990s.

These vulnerable companies underscore an unsettling reality about the world’s big economies: While unemployment in the US and parts of Europe are at multi-decade lows, a growing number of businesses may be held together by little more than cheap financing, instead of their ability to sell things and make a profit. These factors suggest an economy that’s becoming less dynamic and more vulnerable to shocks, and some economists say ever-lower interest rates are the main reason.

“You have delayed the normal lifecycle of companies with low interest rates,” said Alberto Gallo, a portfolio manager at Algebris Investments. “You keep alive business models that are unsustainable.”

Judgement day could be approaching. The spread of Covid-19, the disease caused by a new coronavirus, is likely to take a bite out of global economic growth. That’s caused the junk bond market—a source of funding for many of these risky companies—to wobble, potentially closing off their route for refinancing. In a sign of fear, risky bond yields spiked relative to Treasuries to more than 5 percentage points on Feb. 29, the widest spread in more than a year.

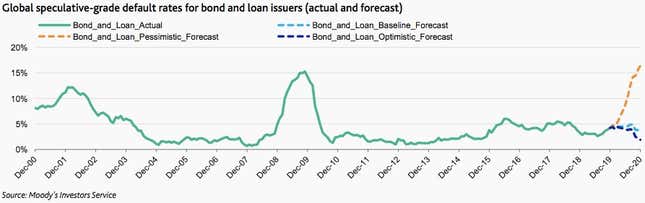

The question is whether central bank officials can, yet again, seduce markets into accepting lower interest rates. If not, a wave of defaults could be on the way. Even companies that have poor fundamentals have been able to refinance their debts at lower interest rates, according to John McClain, a money manager at Diamond Hill Capital Management, which oversees $21 billion in assets. “I think we are going to see some spectacular failures in 2020,” he said.

US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell surprised markets with an interest rate cut (with more expected to come) on March 3 to a range of 1% to 1.25%. Junk bond spreads briefly showed signs of normalizing after the Fed’s emergency adjustment, and the 10-year US Treasury yield—the benchmark for global financing—dropped below 1% for the first time in history.

Zombie companies have contributed to the glut of $3 trillion of risky borrowing around the world, and central bankers are right to be worried about a panic that could make refinancing more difficult. It remains to be seen whether Powell and his central bank peers can contain the fallout.

Wounded unicorns

Ask a bond investor about corporate zombies and they all seem to have their favorite examples. Companies like Intelsat, Community Health Systems, and Range Resources have each been beset by unique issues, but the commonality between them is that they don’t produce enough cash to pay the interest on their debts, according to FactSet data.

Intelsat is a satellite company that’s sitting on potentially valuable spectrum that could be used for 5G networks. The Luxembourg-based based firm is also sitting on about $14 billion of debt and lost more than $900 million last year, the third straight year of increasing losses. Meanwhile, US hospital chain Community Health Systems (CHS) also has a mountain of debt and has struggled as make ends meet amid population flight from rural areas. CHS and Intelsat didn’t provide comment.

Range Resources borrowed $550 million in the junk bond market in January to refinance debt coming due during the next two years. The oil and natural gas company has reported net losses during four of the past five years, and crude oil prices have dropped more than 30% this year. A spokesperson for the company said Range Resources expects its interest coverage ratio to improve in the near future.

“If you haven’t cleaned up your balance sheet now, whenever we get a real pullback, you’re going to see some real trouble,” McClain said of highly indebted companies. Like other investors and analysts, he thinks a number of venture-capital funded companies with high valuations—privately funded “unicorns” with price tags of more than $1 billion—are effectively zombies as well.

“Any large-scale unicorn that doesn’t make money and has no path to short-term profitability fits the bill to me,” McClain said. “2019 was the year of wounded unicorns, and in 2020 I think we’re going to see some dead ones.”

Junkier than ever

There’s a close link between lower interest rates—central banks’ primary weapon for giving the economy a boost—and the stock market’s share of zombie companies, according to BIS economists Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann. They found that these weaker companies are spreading because zombies aren’t dying. That is, they’re staying in a “zombie state” for longer instead of regaining their corporate health or reorganizing in a bankruptcy, and potentially weakening economic productivity.

“How can corporate zombies survive for longer than in the past?” they wrote. “They seem to face less pressure to reduce debt and cut back activity.”

There’s more junk debt than ever—and it’s getting junkier. The stock of non-financial corporate bonds reached a record $13.5 trillion at the end of last year, boosted by an added $2.1 trillion of borrowing in 2019, according to a report by the OECD, an intra-governmental organization. Compared with other economic expansions, this time the credit is of lower quality, has longer maturities, and has fewer protections for investors.

Interest rates have been dropping since the 1980s, (and even longer if you go back far enough), but they got a shove lower after the recession in 2009, in response to millions of jobs losses. Central banks did everything they could think of to spur lending and put people back to work, even as interest rates approached or fell below zero. Policy makers bought trillions of dollars of less risky government bonds, in an effort to force investors to take more risk, and ultimately to put more money in those workers’ pockets.

It worked—at least sort of. With government bonds yielding so little, money has flooded into markets for stocks, junk bonds, and venture capital. That’s means it’s relatively easy for some entrepreneurs to raise money and start a business. After a deep recession a decade ago, the job market has gradually improved.

The trouble with such low interest rates is that capital gets doled out inefficiently, said Davide Oneglia, an economist at TS Lombard. Central bank efforts to boost economic growth can encourage companies to take on more debt, and governments and corporations in particular have gorged on it. The ratio of debt-to-gross-domestic-product reached a record 322% (pdf) in September, with total debt reaching close to $253 trillion, according to trade group Institute of International Finance.

Low interest rates filter through the banking system because they encourage loan forbearance. On paper at least, a company’s debt service ratio can improve when interest rates decline. “You don’t feel guilt rolling over the debt,” Oneglia said.

Instead of defaulting, companies can end up tying up resources—talented employees, and capital—that could be more useful somewhere else. The zombies “are still competing for business, sometimes uneconomically,” Noel Hebert, global director of fixed-income, currencies, and commodities strategy at Bloomberg, wrote in an email. “Central bank accommodation (particularly to the excess that it is now) is ultimately deflationary because you end up with a lot of dead corporate weight.”

No simple options

Indeed, BIS economists argue that lower interest rates can be a vicious cycle. Lower rates can beget more zombie companies, crowding out resources that could have been available for healthier enterprises. This in turn weakens the economy, causing lower interest rates and sustaining more companies with weaker finances.

Some investors think a recession and more defaults could be a good thing. Bankruptcies “wipe the slate clean and address the issue at hand,” said McClain of Diamond Hill. A recession, likewise, could reallocate capital to better, more dynamic companies.

That is unless the economy is already too brittle and larded with debt to handle the shocks. An economic slowdown half as severe as the one in 2008 would put as much as $19 trillion of debt—nearly 40% of the corporate borrowing in major countries—at risk of default, according to the International Monetary Fund. A wave of bankruptcies would damage the economy and put many people out of work.

This suggests policy makers have no simple options. Allowing interest rates to jump higher could set off a string of defaults, threatening livelihoods. But delaying the day of reckoning is showing few signs of bringing zombie companies back to life, and there are signs that current policies are starting to backfire. In the worst case, they may be setting up another debt crisis.