Faced with a global pandemic unprecedented in modern times, groceries around the world are under siege.

Shelves have been stripped bare and online demand has soared far beyond their capacity to meet it. Grocers are begging customers to buy only what they need. Some stores are rolling out “elderly-only” hours to protect older shoppers, who are particularly vulnerable to Covid-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

The crush of demand has hit online grocery delivery companies particularly hard. Late on March 18, Ocado, a 20-year veteran of UK online grocery sales, suspended all access to its website until Saturday (March 21). Melanie Smith, Ocado’s retail CEO, said the temporary closure would let it “complete essential work that will help to make sure distribution of products and delivery slots is as fair and accessible as possible for all our loyal customers,” in a note on what remained of the company’s website.

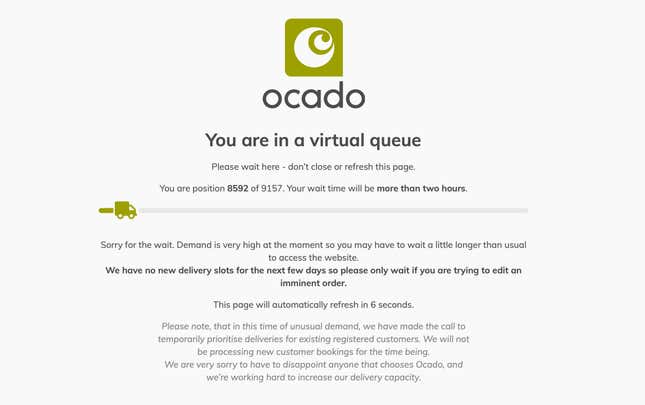

Ocado had fought to keep its website running, even after previously taking its app offline. When the panic buying began, Ocado advised customers to place orders several days in advance. Then it stopped taking new customers entirely, introduced a “virtual queue” to access its website, and asked people to share delivery slots with neighbors. A few hours before Ocado suspended its website, there were more than 9,000 people in that virtual queue, with an expected wait time of over two hours.

“The amount of demand is simply unprecedented,” Ocado chief financial officer Duncan Tatton-Brown said in an update to investors yesterday (March 19), likening the surge in website traffic to a “denial-of-service attack.” He said Ocado’s biggest current bottleneck is its ability to process orders through its fulfillment centers. If the company didn’t have capacity limits, Tatton-Brown said, it would be doing five to 10 times its sales volume.

In some sense, Ocado and the wider British online grocery industry are victims of their own success. While American companies from dot-com bust Webvan to Silicon Valley darling Instacart to Amazon have spent years and billions of dollars in venture-capital funding trying to popularize grocery delivery in the US, with varying degrees of success, grocery delivery is much more established in the UK. The system worked, at least until coronavirus happened.

An online grocery success story

Founded in 2000 by three former Goldman Sachs bankers, Ocado has been delivering groceries to UK households for the better part of two decades. The company operates out of centralized warehouses in England where it stocks and dispatches goods, either straight to customers or via smaller fulfillment sites. In 2010, the year Ocado went public on the London Stock Exchange, it delivered 100,000 orders in a week for the first time.

In 2019, Ocado claimed a 14% share of the UK online grocery market, with £1.6 billion ($1.87 billion) in sales in its core retail business and nearly 800,000 active customers, according to its recent annual report. (Ocado also makes money from a “solutions” business that builds out delivery software and fulfillment services for other grocers in the UK and internationally.) Ocado has historically partnered with upscale supermarket Waitrose but last year sold 50% of its business to department store and grocer Marks & Spencer for £750 million. It will begin delivering M&S goods after the Waitrose partnership expires this September.

While Ocado is most synonymous with grocery delivery in the UK, other supermarkets like Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Asda, and Iceland also offer a combination of grocery delivery and “click and collect,” in which groceries are assembled and packed for customers to pick up.

These services are also now under immense pressure. A quick search of Iceland’s website for multiple London neighborhoods showed all delivery slots booked up for the next week. Sainsbury’s has paused new registrations for both delivery and click-and-collect customers, “due to the huge increase in online orders,” the company says in a message on its website. Delivery and click-and-collect slots in certain neighborhoods are sold out at Asda through April 10, the furthest out date currently available, and the store has limited customers to three of any product across all food, toiletries and cleaning items to prevent hoarding.

It’s even worse in the US

The situation is likely to be even worse in the US, where grocery delivery is less established and successful. Webvan, a startup that promised to deliver groceries within 30 minutes of ordering, was one of the most spectacular flameouts of the dot-com bubble of the early 2000s. Amazon has chased online grocery since 2007, and purchased upscale grocery chain Whole Foods in 2017, but grocery remains a small part of its overall e-commerce business. Instacart, a startup founded in 2012, has been hampered by near-constant disputes with workers, whom it hires mainly as contractors without employer-sponsored benefits like paid-time off and health insurance.

One of the oldest US online grocers is privately held FreshDirect. Like Ocado, it was founded by a former banker, and launched its delivery service in the early 2000s. FreshDirect has said it became profitable in 2010. The bulk of its operations are in the greater New York area, where it typically charges from $5.99 to $7.99 per delivery.

Analysts at Bernstein estimate that less than 1% of the US uses online grocery, compared to 7% of the UK. Online grocery globally is estimated at 1.7% of e-commerce. Bernstein’s analysts said in a March 12 report that existing online grocery companies in the US offered lower product availability and quality than it typically takes to convince customers to place their orders online. By contrast, they said, Ocado excels in these categories, with nearly double the product availability of its US competitors and high-quality fresh food operations. “The reason why grocery e-commerce in the USA has been low is … because the service levels are too low,” Bernstein’s analysts wrote.

That the UK has more fully developed online grocery services could be a boon for consumers and the nation as everyone seeks to keep food moving amid increasingly strict coronavirus measures. But even companies like Ocado, as this week has made clear, will struggle to scale up with the sudden and unprecedented spike in demand. “Getting consumers to trial out a new service is always the hardest first step,” Bernstein’s analysts wrote in a note on March 19. “Right now, most of the world are doing their first grocery e-commerce shop.”