It started out as the “Wuhan virus”, with everyone from researchers to news outlets—including those inside China—referring to it as such. Then it was the “Wuhan coronavirus” and “China coronavirus,” and subsequently 2019-nCoV. Finally, on Feb. 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) gave the disease an official name: Covid-19.

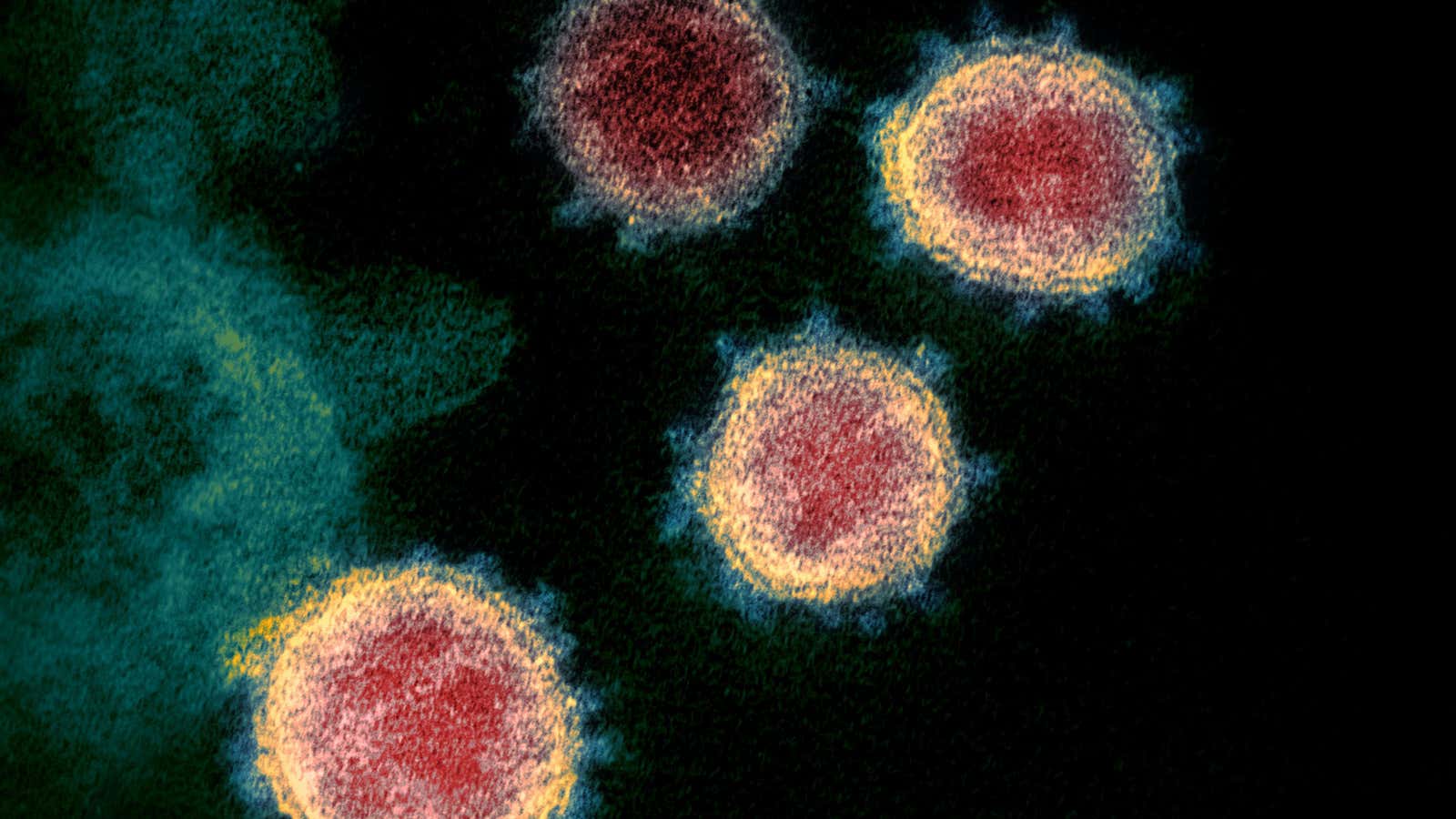

To be clear, Covid-19 refers to the disease. “Co” refers to corona, “vi” to virus, and “d” to disease. The virus that causes the disease is SARS-CoV-2, which was named by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The “SARS” part of the name refers to the new coronavirus’ genetic link to the virus that caused the 2003 SARS outbreak. So one tests positive for SARS-CoV-2, not Covid-19, as it’s the virus and not the disease that does the infecting. The WHO lays out this distinction clearly on its website.

But despite the virus having a full name, the WHO almost never refers to it as SARS-CoV-2. Instead, it uses “the virus responsible for Covid-19” and “Covid-19 virus.” Technically, the latter is redundant: spelled out, it would essentially read “coronavirus disease virus.”

The broader contention over how to label the new coronavirus underscores how in the combustible mix of a public health crisis and geopolitical rivalries, names do far more than convey information. They draw battle lines. And as countries grapple with spiralling case counts and overrun emergency rooms, a fierce struggle is underway to command the pandemic’s narrative.

In recent days, as the number of new reported cases slows in China, the country has sought to play up the storyline that it bought the world time, even suggesting that the US is to blame for the virus. Meanwhile, US politicians including president Donald Trump have insisted on using terms like ”Chinese Virus,” and a White House official called it “kung-flu” in front of a Chinese-American journalist. In this context, what the WHO—as a neutral, international agency—calls the virus suddenly carries a lot of weight.

The WHO writes on its website that it steers clear of SARS-CoV-2 because “using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations, especially in Asia which was worst affected by the SARS outbreak in 2003.” At a press briefing on Feb. 13 (pdf), WHO executive director Michael Ryan noted that SARS-CoV-2 is a technical term for virologists in labs, while Covid-19 is a term for the average person. “We’re trying to relate the virus to the world, the experience that people have with the virus… so I don’t think there’s any inconsistency,” he said.

In a statement to Quartz, the WHO added that “under agreed lines between the WHO, the World Organization for Animal Health, and the Food and Agriculture Organisation… we had to find a name that did not refer to a geographical location, an animal, an individual, or group of people, and which is also pronounceable and related to the disease.” However, on its list of pandemic and epidemic diseases, there are several other diseases that explicitly refer to a geographic location: Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS); Lassa fever, referring to a town in Nigeria; and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever.

In journals like the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, scientists use both “Covid-19” and “SARS-CoV-2” to refer to the disease and virus respectively, but never the WHO’s term “Covid-19 virus.” Similarly, in op-eds published by leading epidemiologists, the authors are similarly assiduous in distinguishing between the disease and the virus. So why is the WHO so reluctant to use the name SARS-CoV-2?

Some have argued that SARS-CoV-2, as a name, can cause confusion. In a letter published last month in the Lancet, six co-authors from China (including three from the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention) argued that naming the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is “truly misleading” because it “implies that it causes SARS or similar,” especially for those without technical expertise in virology. The authors added that the name SARS-CoV-2 “might have adverse effects on the social stability and economic development” of countries experiencing the epidemic, as “people develop panic at the thought of a re-occurrence of SARS.” Instead, they proposed naming the virus human coronavirus 2019, or HCoV-19.

Responding directly to the letter a month later, a group of 12 scientists based in the US, Hong Kong, and mainland China argued that SARS-CoV-2 is in fact an appropriate name for the new coronavirus. The name, they argued, “does not derive from the name of the SARS disease,” but refers to its links with the viruses in the SARS viral species. “In other words, viruses in this species can be named SARS regardless of whether or not they cause SARS-like diseases,” they wrote. The authors also argue that far from damaging social stability, “keeping SARS in the names of viruses of that species would… keep the general public vigilant and prepared to respond quickly in the event of a new viral emergence.”