What “lean startup” got wrong about how to build companies

In 2005, an entrepreneur named Steve Blank published a book in which he argued that most startups fail because they don’t understand their customers. He was speaking from experience. Blank had co-founded four startups and advised or worked at several others.

In 2005, an entrepreneur named Steve Blank published a book in which he argued that most startups fail because they don’t understand their customers. He was speaking from experience. Blank had co-founded four startups and advised or worked at several others.

Based on what he learned at those companies, and from the many failures of the dotcom bust, Blank believed the difference between the successes and the failures was a willingness to get outside the office and test ideas and products by talking to the very people you hoped would buy them.

The success of his book, Four Steps to the Epiphany, landed Blank a gig teaching entrepreneurship at Berkeley. Six years later, one of his students, an entrepreneur named Eric Ries, published his own book with a similar thesis but a better name: The Lean Startup.

For all the attention paid to the musings of tech icons like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, few people have had as much impact on how startups are run in this century as Blank and Ries.

The “lean startup” is “arguably one of the biggest ideas in business in the last 20 years,” says Jeffrey Bussgang, a venture capitalist at Flybridge Capital Partners and a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School. “It’s completely transformed the ways startups and entrepreneurs approach the business-building process. And it did it at a time when the environment was ripe for such an idea.”

Web and cloud computing were lowering startup costs, and making experimentation easier. The architects of the lean startup argued that entrepreneurs should prioritize talking to customers and adopt an iterative approach: building “minimum viable products,” running experiments, collecting data, and “pivoting” as necessary in search of “product-market fit.” Borrowing from the concepts of lean manufacturing, agile development, and design thinking, they preached a bias toward action and promised to turn entrepreneurship into a science—or at least something like it. By doing so they would help more startups succeed.

But startups keep failing—some of them rather spectacularly. The extremely public stumbles of WeWork, Theranos, Uber, Away, and even the Fyre Festival have drawn new attention to the many ways in which startups can go awry. In some of these cases, companies that seemed to have product-market fit found other ways to fail, by scaling too fast, creating and tolerating toxic cultures, and even engaging in fraud, all papered over, at least for a time, by massive amounts of venture capital flowing into the startup sector.

Academics and other startup experts are now debating what the lean startup got right and got wrong, and what it left out. There’s broad agreement that its experimental approach was a step forward. But the critics say it’s not right in every situation. Its focus on products and customers can draw attention away from other important aspects of running young companies.

Scott Stern, a professor at MIT and co-author of forthcoming textbook on startup strategy, says too much focus on winning customers can lead to problems. With the Fyre Festival, he jokes, “it was test and pivot, right to jail.” And as Theranos found out the hard way, after allegedly faking a demo of its blood-test technology to the drugstore chain Walgreens, “there is no amount of customer feedback that can solve the problem of whether something works technically,” Stern notes.

As important as customers are, successful startups also require strong organizations, technologies, and strategies. But the advice most startups get focuses almost obsessively on products and customers.

“Startups, to be successful, have to build something people want,” Sam Altman, the former head of startup incubator YCombinator, has said. “If you get that right, you can get everything else wrong—pretty much… [Making something people want] is probably the most important piece of startup advice in the early days. This is the only thing that matters. You have to do this. You can ignore all the other advice.”

Uber certainly tested that theory. It built a product people badly wanted and then steamrolled local rules, sabotaged competitors, and created a toxic culture where sexual harassment was common. Today it’s a public company worth nearly $35 billion—and investors, employees, and the public are demanding better behavior.

“Entrepreneurs are hearing lots about the customer and much less about the team,” according to Kit Hickey, co-founder of Ministry of Supply, an apparel tech company in Boston, and entrepreneur-in-residence at MIT. This leaves them woefully underprepared for the reality of running a startup, stealing focus that instead might have been put on things like company culture and contributing to the creation of problematic work environments.

For this field guide, Quartz spoke to founders, investors, and experts to discover why startups fail, through the lens of what the lean startup gets right, what it misses, and what comes next.

Table of contents

The quest for product-market fit | Founder failure | Failing by scaling | Can true innovation be tested? | People over products

The quest for product-market fit

Vera Wang opened her first bridal boutique in 1990, more than 20 years before “lean startup” entered the business lexicon. At the start, she mostly sold clothes from other designers. “But then I put in one dress of mine to see if it would sell,” she said in an interview with Harvard Business Review. “And then two. And then three. And then five. And eventually it became completely me.”

Wang’s approach should sound familiar to lean-startup devotees. Rather than launching an entire line of dresses, she ran a test to see how her designs would perform with customers. She learned from that experiment and then ran another one, until, eventually, she was designing all the dresses sold in her store.

The heart of the lean startup approach is a cycle that Ries describes as “build-measure-learn” and it starts by “[entering] the Build phase as soon as possible with a Minimum Viable Product (MVP).”

Nick Swinmurn took this approach to founding online shoe retailer Zappos. You might think the first step in starting a shoe retailer would be to acquire some shoes but, as Ries recounts in his book, Swinmurn took a different approach. To test his “hypothesis” that people would buy shoes online, Swinmurn went to a bunch of local shoe stores and, with their permission, took pictures of their inventory and posted them on his new site. If one of his users bought the shoes on Zappos.com, he returned to the store, bought the shoes himself, and mailed them.

With this hacky test, Swinmurn was able to validate his hypothesis without raising money, acquiring inventory, or striking partnerships. Like Wang, he was able to confirm, quickly and cheaply, that he was onto something.

Ries didn’t coin the term “minimum viable product,” but he popularized it and put it at the center of a theory of startup success. Today, it’s one of the first things YCombinator teaches in its Startup School curriculum. The point is to learn something about what customers really want, which was the overriding focus of Blank’s earlier book. Depending on what you learn, Ries says, you either “pivot” or “persevere.”

The goal of the build-measure-learn process is for startups to find the elusive “product-market fit,” a concept that originated with venture capitalist Marc Andreessen. Ask entrepreneurs and VCs to pick between whether “team, product, or market” is most critical to the success of a startup, and “many will say team… If you ask engineers, many will say product,” Andreessen wrote in a 2007 essay. “I’ll assert that market is the most important factor in a startup’s success or failure. In a great market—a market with lots of real potential customers—the market pulls the product out of the startup.”

The quest for product-market fit has become, as Blank puts it, the “holy grail for entrepreneurs.” If you have to ask whether you’ve found it, Ries writes, “you’re not there yet”—YCombinator’s startup school says the same thing.

It isn’t easy to build, test, and learn effectively. What do you test? And how do you interpret the often hazy results? But, overall, the evidence suggests it helps. A few years ago, researchers at Bocconi University in Milan conducted an experiment to see if a quasi-scientific approach to entrepreneurship worked. They randomly split 116 Italian startups into two groups and provided them different training. All the entrepreneurs learned common concepts like minimum viable product, but only one of the groups was taught to think in terms of theories, hypotheses, and experiments. Fourteen months later, the entrepreneurs who’d received the more experiment-focused training had higher revenue.

To some observers, the high-profile startup failures of recent years are evidence that the experimental approach to startups still isn’t fully appreciated.

“Why is WeWork where they are right now? Because they forgot the lessons of the lean startup. They scaled things that didn’t work, in the name of ‘Go big or go home,’” says Eric Paley, a partner at the seed fund Founder Collective. The product-market fit was there, but small experiments got skipped over in favor of rapid, outsize growth.

Founder failure

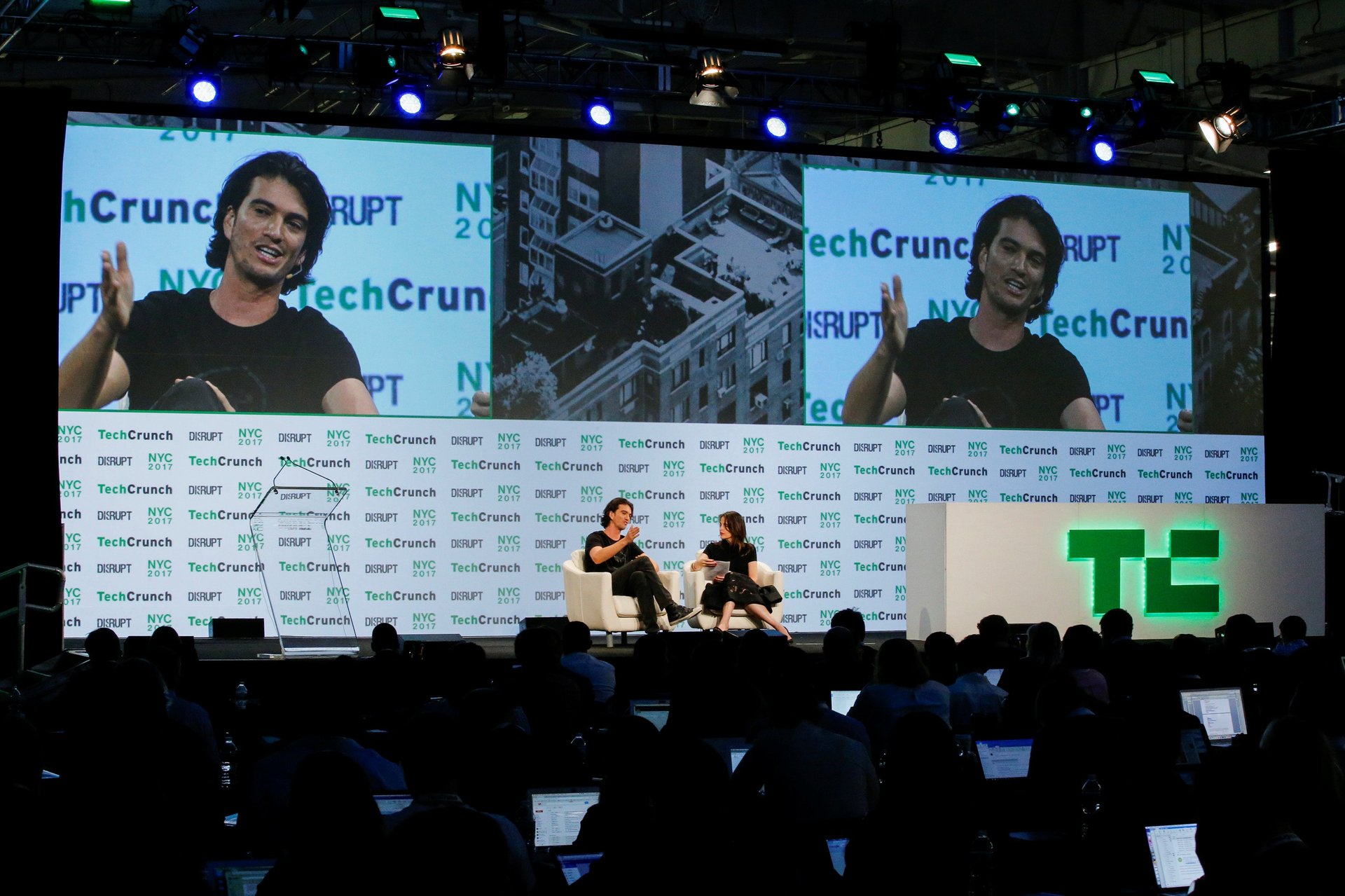

It’s impossible to explain WeWork’s downfall without mentioning its co-founder and original CEO, Adam Neumann. He led the company to a valuation of $47 billion through a combination of “charisma and soaring rhetoric,” as New York magazine’s Reeves Wiedeman put it.

Neumann created a “reality distortion field,” a term originally from Star Trek that was later applied to Steve Jobs’ ability to motivate the team at Apple building the Macintosh computer to believe they could accomplish something extraordinary in a short amount of time. “A lot of these spectacular, late-stage startup failures have got crazy amounts of the reality distortion fields going,” says Tom Eisenmann, a professor at Harvard Business School, citing companies like Theranos and Better Place, the much-hyped battery charging company that filed for bankruptcy in 2013. Neumann “had the ability to cast this Rasputin-like spell,” he says.

Charisma is generally an asset for founders, who have to convince employees, customers, and investors to believe in their company and take risks. But it can become a liability when it gets in the way of critical feedback.

“If the lean startup movement is right, on its own terms, then who the founders are shouldn’t matter,” says Stern. “All that should matter is the data. But of course the founders matter—they’re founding for a reason.” That’s a bit strong; no one really thinks founders don’t matter to a startup’s success. But Stern’s point is that the focus on customers, markets, and product-market fit shifts a startup’s focus outward, emphasizing external factors at the cost of internal ones.

Multiple academic studies have found that “people problems” are the most common source of startup failures—more common than a lack of product-market fit. A CB Insights analysis of news reports and blog posts by founders determined that “no market need” was the most commonly cited problem ascribed to failed startups. But they also found that a third of the failed companies also suffered from either “not [having] the right team” or “disharmony among the team/investors.”

“It’s very much the natural inclination of founders to go and focus on the product, the market. Those are the things they are passionate about,” says Noam Wasserman, dean of Yeshiva University’s Sy Syms School of Business. “Unfortunately, that almost single-minded focus crowds out [making] sure that they have a strong foundation in terms of the people, in terms of the team.”

When Hickey attended business school at MIT in 2011, she took lots of classes on developing products to prepare herself to found a startup. But as a founder, she ended up spending 75% of her time on people issues.

“Students [of entrepreneurship] are really eager for resources” on people issues, says Erin Scott, a senior lecturer at MIT. But there are fewer “readily available resources” on these issues, she says, which is why she and Hickey co-developed a course all about entrepreneurial teams.

The first people-related mistake many founders make is hiring people too much like themselves, Yeshiva’s Wasserman argues in his book The Founder’s Dilemmas. That homogeneity has some short-term benefits, Wasserman says, because likeminded people may develop trust more quickly. But it’s short-sighted.

“As tempting as it is to go with the ‘comfortable’ and ‘easy’ decision to found with similar cofounders, founders may be causing long-term problems by doing so,” he writes.

That’s particularly true when founders hire or co-found with friends or family members. WeWork badly needed someone to check Neumann’s excesses, but arguably the second most influential person within the company was Rebekah Neumann, a senior executive and Adam Neumann’s wife.

“There’s an old saying: Monarchy is the greatest method of decision-making in the world, as long as the monarch is infallible,” Wasserman has said. “Recent history shows that even the most iconic founder is far from infallible, especially if their control is unchecked.”

Failing by scaling

The early mistakes that founders make are amplified as a startup scales, especially if they raise large amounts of venture capital. “When you put capital against a business, it will only multiply what it is you have,” says Founder Collective’s Paley. “It will multiply the problems, and it will multiply the successes. We have an entire industry right now that is funding systems that don’t work.”

When I asked Blank, one of the lean startup’s original architects, about recent startup failures like WeWork, he said “most of it is driven by investors.” (Ries did not respond to an interview request.)

“The VCs’ interests are not in building a long-term, sustainable company,” says Blank. Instead, he argues, they’re focused on finding a profitable exit, and will sometimes pressure founders to adopt “vanity metrics” in order to achieve it. “The rule is to maximize revenue for the investors, and after you find product-market fit they will do whatever is necessary to go do that.”

By the summer of 2015, Baroo, a dog-walking service founded a year earlier in Boston, seemed to have achieved product-market fit. Its first winter of operations had gone well, according to a case study Eisenmann wrote about the company for Harvard Business School. Baroo offered its “pet concierge” service to upscale apartment buildings, which were happy to have an additional amenity to advertise to tenants. Baroo’s board decided that it was time to “expand aggressively and to replicate the model in another city, provided that the proof of concept could attract venture capital,” according to a case study Eisenmann wrote on the company.

It didn’t go well. The new buildings Baroo partnered with in Chicago and Washington DC had different needs and different customers. The third-party technology Baroo had relied on didn’t scale well. Hiring general managers in new cities proved difficult, and the board began to squabble.

“We were growing so fast that we had trouble hiring enough new providers—a problem made much worse by high rates of provider turnover,” Baroo co-founder Lindsay Hyde says in the case study. “So, our really good walkers sometimes ended up working 12-hour days. We were shuttling them all over the city and paying them hourly. We were burning out our best walkers and burning through our cash.”

The cash ran out before new cash could be raised, and by 2018 Baroo had shuttered its operations. Eisenmann now teaches the case as a way to press students on whether or not they should take venture capital and attempt to quickly scale.

Sometimes scaling as fast as possible really is justified, according to LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman and veteran entrepreneur Chris Yeh, who co-authored Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies. The book opens with an account of Airbnb’s success through “an aggressive, all-out program of growth that we call blitzscaling. Blitzscaling drives ‘lightning’ growth by prioritizing speed over efficiency, even in an environment of uncertainty.”

Airbnb benefits from network effects; the more people use it, the more valuable it becomes. Markets with network effects can take on a winner-take-all dynamic, meaning the first company to scale might be able to beat out the one with the best product.

Baroo didn’t benefit from the network effects that propelled Airbnb or Facebook. Neither did WeWork, according to Hoffman and Yeh, but the company scaled rapidly anyway, with predictable results.

How can a founder know if they’re in a winner-take-all market? Not through customer feedback or A/B testing. Blank’s first book on customer discovery acknowledges as much with a section on picking markets. As the principles of lean startup have been popularized, this point has gotten lost.

Groupon exemplifies this dynamic: It experimented, pivoted, found product-market fit, scaled rapidly, and failed anyway.

“Groupon started out as a business called The Point, which was designed to help people do petitions,” Reis explained in 2012 in a video for Fast Company. It “didn’t work.” The point of The Point was that a petition could only be effective if a certain number of people signed on. After a year of effort and with little to show for it, the founders took this insight and applied it to coupons. If enough people signed up for a pizza discount, the coupon would be issued; if they didn’t, it wouldn’t. In Ries’s telling, this was an effective repurposing of the original vision. But it’s hard not to see the pivot as an abandonment of the initial idea.

Either way, Groupon prospered as a discount platform, raising over $1 billion in financing in just two years and reaching unicorn status faster than almost any company in history.

But it had two problems. The first was that it wasn’t prepared to manage such rapid growth. The leadership team had “no patience for bureaucracy,” reported The Verge. The acquisition of a major European competitor in 2010 presented difficult management challenges.

“Because it was buying up companies, rather than scaling out its own technology overseas, Groupon was basically running on dozens of incompatible platforms,” Ben Popper reported for The Verge. “According to a source familiar with the overseas business, in many [of the acquired company’s] outposts, employees weren’t using Groupon’s platform at all; they were literally selling deals over the phone and sending the results back to Chicago in the form of spreadsheets.”

Groupon’s biggest challenge was its business model. There was always a limit on how many discounts retailers could offer, and the market contained few barriers to competition. In the US, Living Social quickly became a rival, courting a market of consumers who were, almost by definition, price sensitive.

No amount of growth could outrun these problems, and in 2013 founder and CEO Andrew Mason was fired by the board. In the years since, the company has scaled back substantially. Though still a public company, its valuation is less than half a billion dollars, as of this writing. The company Ries had held up as a lean startup success story had failed for reasons that were foreseeable, but not testable.

Can true innovation be tested?

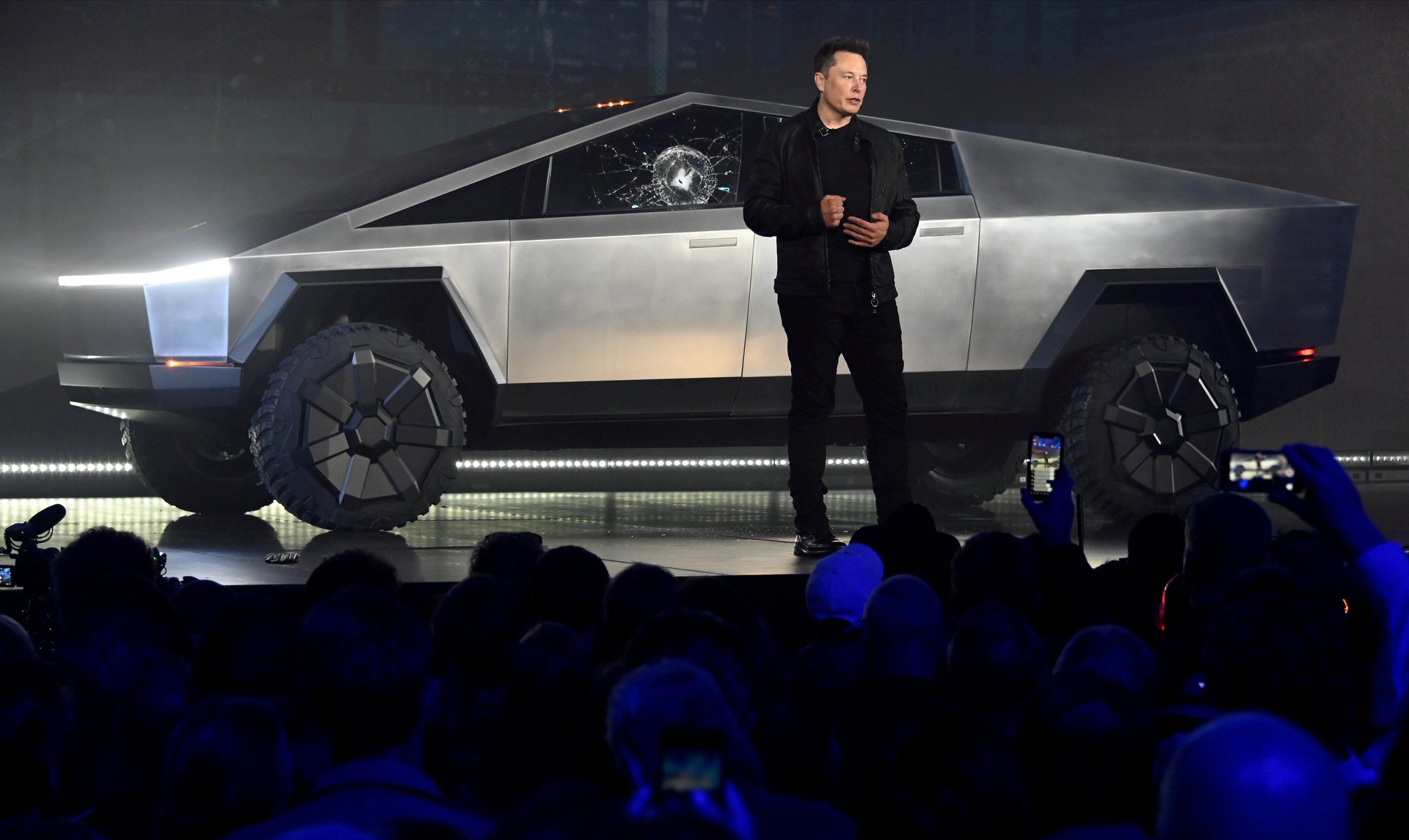

Elon Musk didn’t start Tesla with a hypothesis that he could test. Instead, in 2006 he published his “master plan” for the company:

So, in short, the master plan is:

Build sports car

Use that money to build an affordable car

Use that money to build an even more affordable car

While doing above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options

Don’t tell anyone.

Musk believed that the cost of building electric vehicles would drop significantly over time, creating a mass market. Building a sports car would help pay for the R&D to drive costs down and would position his company to succeed in that mass market when it eventually arrived.

Nothing that early Tesla customers could say would confirm or deny that belief. No experiment could test it. In fact, 14 years later it’s still not clear whether or not Musk was right.

“Arguably the single most important [startup] success story of the last 10 years is actually completely anti-lean startup,” says Stern. “Does that mean Elon Musk doesn’t use experiments? Of course it doesn’t. But it means that there was not the primacy on product-market fit for the mass market.”

This is the most common criticism of the lean startup: that it pushes founders toward incremental ideas that are easy to test.

“Lean startup is the metaphorical equivalent of a prompt to look for your keys under the streetlight,” wrote four business school professors, including Stern, in an essay published last year:

Lean startup prompts low-cost startup ideas or search where the experimental ‘light’ is: where beta products can be rapidly developed, and where customers and investors can already easily understand and agree (or disagree) with what a startup is doing. But the problem is that the resultant products and opportunities are more likely to be incremental, and importantly, also obvious to other potential entrepreneurs and innovators. Furthermore, any customer signal will likely lead startups to pivot toward more incremental and obvious opportunities.

Peter Thiel leveled a similar criticism in his 2014 book Zero to One. “Would-be entrepreneurs are told that nothing can be known in advance,” he wrote, mentioning lean startup by name. “We’re supposed to listen to what customers say they want, make nothing more than a ‘minimum viable product,’ and iterate our way to success.” The result, he argued, would be incremental innovation, like “build[ing] the best version of an app that lets people order toilet paper from their iPhone.” (To be fair, writing this in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, that suddenly sounds like an interesting idea.)

This isn’t totally fair to Blank and Ries, both of whom discuss the role of vision in their original books. “You don’t sign up for a job when you start a company,” Blank told me. “You sign up for an insight.” Musk had an insight that was not testable, but that would direct the company toward narrower decisions that would be. Still, Blank acknowledged that this point can get missed amid the search for product-market fit.

People over products

Jim Barksdale, the former CEO of Netscape, used to say that “We take care of the people, the products, and the profits—in that order.” Lots of the startup failures and scandals of the past few years can be traced to ignoring that philosophy.

“‘Taking care of the people’ is the most difficult of the three by far,” writes Ben Horowitz, a VC at Andreessen Horowitz, in his book The Hard Thing About Hard Things, quoting Barksdale. “And if you don’t do it, the other two won’t matter. Taking care of the people means that your company is a good place to work.”

Being a good place to work requires a good culture. In a subsequent book, Horowitz, who is on the board of Lyft, argues that Uber tolerated rule-breaking and sexual harassment specifically because its founder had created the wrong kind of culture. “Uber’s culture actually worked exactly as designed,” he writes, citing its embrace of “fierceness” and its mantra to “Always Be Hustlin’.” (Uber has since changed its list of values.)

To Horowitz, Kalanick explicitly created a culture that put crushing the competition above all else, and that trickled down into decisions like HR deciding not to investigate sexual harassment.

Harvard Business School’s Eisenmann says some founders suffer from what he calls a “Peter Pan problem.” They love the camaraderie of early-stage companies, and bristle at the discipline and process that companies need as they scale. In short, they don’t want to grow up.

Founders don’t necessarily show that side of themselves in open, deliberate protest; many times startups simply let their employees down through neglect.

“It’s not until later, sometimes, where entrepreneurs see how much time needed to be spent on managing people and creating a culture that can be scaled,” says Jason Crain, an entrepreneur-in-residence at Amazon who sold his machine-learning startup to the e-commerce giant in 2016.

By the time founders realize the importance of culture, of management, and of treating employees well it’s often extremely difficult to fix what’s gone wrong.

Yeh says he tells founders to apply an early focus on culture and on “ensuring that there is diversity and inclusion from the start.”

But because many founders don’t have much experience, they often approach issues like culture in the wrong way.

“We’ve all been at companies that have these sweeping statements [about mission and culture] but the daily practices don’t fit that at all,” says Hickey. In their course at MIT, she and Scott “try to get founders to think less in sweeping statements,” she says. Instead, they teach their students to think about whether their actual behaviors—from decisions around hiring, firing, and promotions to how meetings are run—match the principles they’ve set for their culture.

That sounds suspiciously like traditional management, which lots of founders ignore and some actively disavow. Too many startups “put everything in the hands of the founder because he’s a charismatic guy,” says Raffaella Sadun, a professor at Harvard Business School whose work has documented the importance of management. “It turns out if you don’t have good HR practices it’s going to be easy for people to misbehave.”

“Startups are particularly susceptible to… believing that they can sustain success without processes for too long,” says Sadun. But “processes matter,” she says, “especially for the growth phase.” (To their credit, Hoffman and Yeh have a whole chapter in their book on the management challenges that come with scaling.)

Why don’t founders prioritize good management? Perhaps it’s because of the Silicon Valley mentality reflected in Jobs’ line that “It’s better to be a pirate than to join the navy.” Sadun sees something else at play. “A lot of the resistance has to do with the fact that the moment you create effective processes, you are effectively making yourself redundant,” she says.

Just like with culture and management, it’s easy for founders to ignore their product’s impact on the world until the damage is done.

“You have got to think about the impact of these products on people,” says Hemant Taneja, a VC at General Catalyst who has been critical of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s early mantra to ‘move fast and break things.’ “It starts with: What is it that the founders are trying to accomplish?” Taneja says. The answer “can’t just be about a product that could grow fast.”

Here again, culture is often the deciding factor; Crain calls it the “tie breaker” in tough decisions. “The faster you try to grow in these complex businesses, the more corners you will have to cut,” Taneja says. “Making those choices is all about culture.”

When they work, startups really can make the world a better place. But just as often they can wreak havoc on their customers, their employees, and even entire cities and countries.

The lean startup gave founders a set of tools to make choices about products and customers. They work better in some cases than in others, but clearly they’re valuable. But what about all the other choices startup founders have to make? And what about the ones they don’t even know they’re making?

In the end, those choices add up, and not just for the startup in question. “Entrepreneurship matters to the economy precisely because it’s the engine by which transformational innovation is scaled,” MIT’s Stern says.

The question is, what, and who, will influence how the next generation of startups chooses to scale.