On Sunday, Feb. 23rd, rumors started that schools in the Lombardy region of Italy—the country’s economic powerhouse—might close. Confirmed cases and deaths from the new coronavirus were soaring. The healthcare system was teetering, and Italy had to dramatically change course in a bid to halt the virus. By evening, the region was in lockdown.

Within 24 hours, Iain Sachdev, principal at the International School of Monza, had organized his teachers and filmed a short video clip for students, faculty, and parents. School would open at 9am on Tuesday, he said. Be patient, he implored. Taking a school online in 24 hours was a massive feat which would be messy. Everyone would be learning.

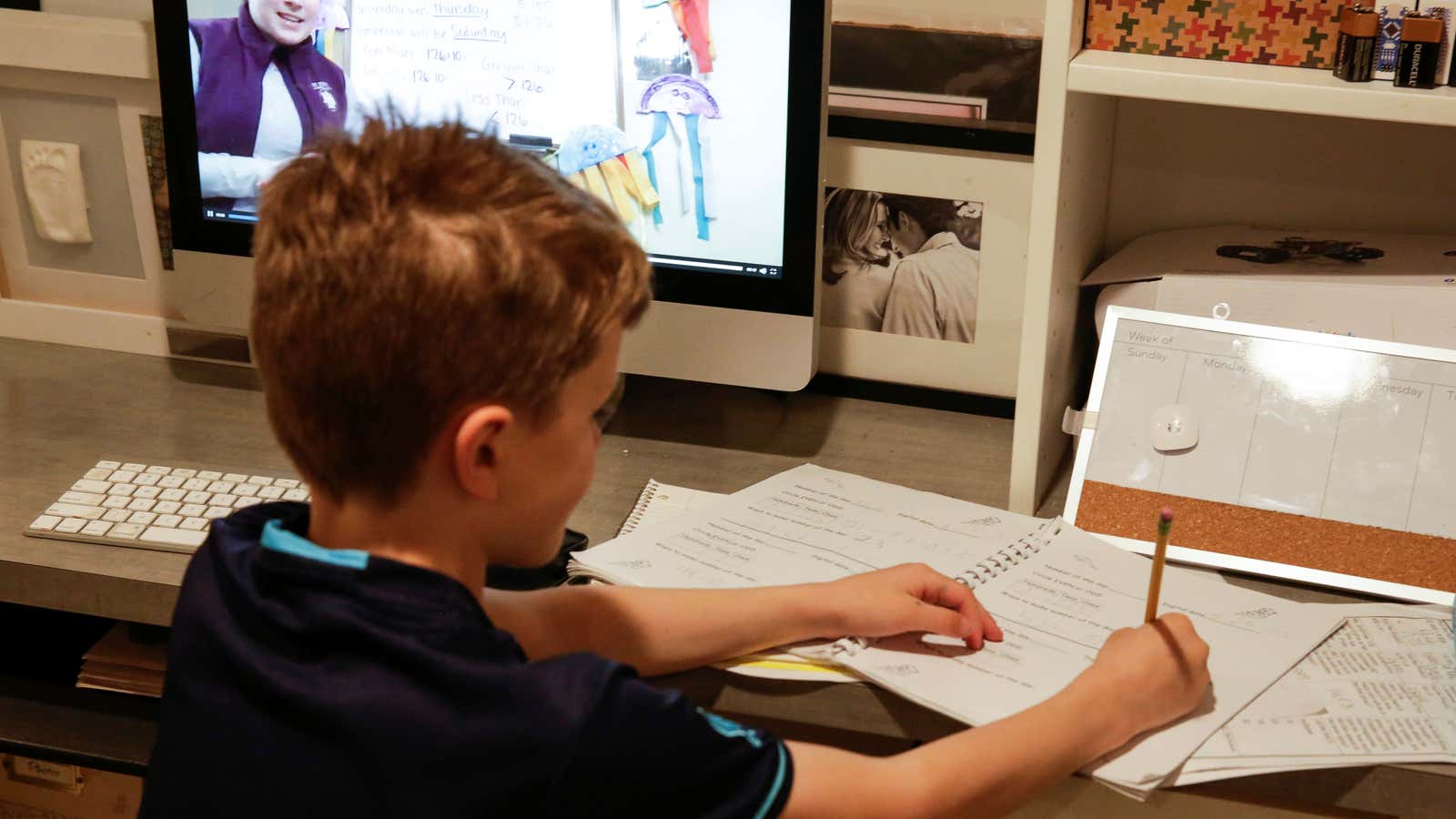

Five weeks later, the school is still running—unfamiliar in many ways, identical in others. Teachers teach via video conferencing every day. Kids participate using Padlet, a virtual post-it note system that lets students share ideas; and Flipgrid, which lets teachers and students create short videos to share. Students do individual work, group work, and confer with teachers when needed. Sachdev has overhauled the schedule from 50-minute units to longer blocks. Teachers no longer use email, but Microsoft Teams.

The International School of Monza is part of the world’s biggest educational technology (edtech) experiment in history. With 1.5 billion students out of school and hundreds of millions attempting to learn solely online, the experiment will reshape schools, the idea of education, and what learning looks like in the 21st century. The pandemic is forcing educators, parents, and students to think critically, problem-solve, be creative, communicate, collaborate and be agile. It is also revealing that there is another way.

“It’s a great moment” for learning, says Andreas Schleicher, head of education at the OECD. “All the red tape that keeps things away is gone and people are looking for solutions that in the past they did not want to see,” he says. Students will take ownership over their learning, understanding more about how they learn, what they like, and what support they need. They will personalize their learning, even if the systems around them won’t. Schleicher believes that genie cannot be put back in the bottle.

“Real change takes place in deep crisis,” he says. “You will not stop the momentum that will build.”

But as tech connects people in their homes, its limitations for learning are on display for all the world to see. The crisis has cast a bright light on deep inequalities not just in who has devices and bandwidth, which are critically important, but also who has the skills to self-direct their learning, and whose parents have the time to spend helping. It is a stark reminder of the critical importance of school not just as a place of learning, but of socialization, care and coaching, of community and shared space—not things tech has hacked too well.

The pandemic is giving tech massive insights at scale as to what human development and learning looks like, allowing it to potentially shift from just content dissemination to augmenting relationships with teachers, personalization, and independence. But the way it is has been rolled out—overnight, with no training, and often not sufficient bandwidth—will leave many with a sour taste about the whole exercise. Many people may well continue to associate e-learning with lockdowns, recalling frustrations with trying to log on, or mucking through products that didn’t make sense.

“This may be a short-term commercial opportunity for some vendors, says Nick Kind, senior director at Tyton Partners, an investment banking and strategy consulting firm focused on education. “But for this to become transformational for teachers and learners, you wouldn’t have wanted to start this way.”

When the storm of the pandemic passes, schools may be revolutionized by this experience. Or, they may revert back to what they know. But the world in which they will exist—one marked by rising unemployment and likely recession—will demand more. Education may be slow to change, but the post-coronavirus economy will demand it.

Equity

Moving the world’s students online has starkly exposed deep inequities in the education system, from the shocking number of children who rely on school for food and a safe environment, to a digital divide in which kids without devices or reliable internet connections are cut off from learning completely.

According to OECD data, in Denmark, Slovenia, Norway, Poland, Lithuania, Iceland, Austria, Switzerland and the Netherlands, over 95% of students reported having a computer to use for their work. Only 34% in Indonesia did. In the US, virtually every 15-year-old from a privileged background said they had a computer to work, but nearly a quarter of those from disadvantaged backgrounds did not. These divides will likely worsen, as staggering job losses and a recession devastate the most marginalized in every society, including all their kids.

Schools face a difficult choice: if they don’t teach remotely, all of their students miss out on months of curriculum. If they do, a sizable group of already disadvantaged students will be left out and will fall even farther behind.

The gap between students isn’t limited to internet access; it’s also about the power and privilege of parents. “If you are called to duty right now as a nurse or delivery person, you have no time for homeschool,” says Heather Emerson, managing director for IDEO’s design for learning group. And not every parent has the level of digital literacy necessary to help their kids shift to online learning.

Schleicher says that his optimism for technology uptake is paired with pessimism about what this means for equity. Those from privileged backgrounds will find the tools they need, through parents or tutors or their better-resourced schools. But those from disadvantaged backgrounds will face multiple challenges, from the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy to the top: food and shelter, which school helped to provide, connections to support children’s learning, and a lack of financial buffers to carry a family through.

“It is clear that this will not reach everyone and it’s not just a matter of access to devices,” he says. “If you don’t know how to learn on your own, if you don’t know how to manage your time, if you don’t have any intrinsic motivation, you won’t be very successful in this environment.”

The OECD is one of many organizations advocating to increase access to open free, online educational resources and digital learning platforms for teachers and students. For schools to succeed, teachers will also need access to training and support.

Meanwhile, the crisis is highlighting the role schools play outside of education. At a moment when schools need to adapt how they teach, many are consumed with how to feed their students. Gwinnett County, Georgia, one of the largest school districts in the US, is feeding 90,000 students a day. “It’s a prime example of how schools have become not just learning institutions, but the heart of the social fabric of America,” Emerson says.

She argues that coronavirus offers an opportunity to see clearly all that teachers are asked to do. That includes everything from meeting the latest state standards, implementing district priorities, mastering new technology platforms, and caring for the physical and emotional well being of their students. She suggests that schools can free up teachers to do more learning.

“What can we do to liberate teachers to focus on their craft?” she said. “And shouldn’t we pay them wages that match the magnitude of their roles they play in our lives?”

Indeed, the pandemic has woken people up to the challenges of teaching and focused some attention on another equity gap: that of pay for teachers. After one day of home schooling in the US, Twitter lit up with calls for teachers to be paid more than investment bankers.

Classrooms

Many schools were woefully unprepared to move online overnight. Those that were ready may hold clues for the promise, and pitfalls, of e-learning.

Students at the International School of Monza all had MacBooks; last August, all teachers were given them too. Sachdev is aware that as an independent school, it was fortunate to have everyone equipped to learn online. But he also said there were still a lot of pieces that had not been pulled together. “We had the systems in place but we never really used them,” he said.

Julia Peters, who teaches economics and individuals and societies at the International School of Monza, says being forced online has allowed her to moved to a more “flipped classroom” in which students do more learning about basic skills and knowledge at home, via videos or platforms, and then come to school online to do work together. “That way, when they come into the classroom we can work on the higher level skills such as analysis and evaluation,” she says. It’s not a new idea at all, but circumstances are forcing adoption.

Another positive, Peters says, is that software like Microsoft Teams allows her to see her students as they are writing. That allows for real-time feedback, rather than waiting for the work to be completed. She has also found ways of reaching struggling students. Her Grade 7 students are preparing an essay on beliefs, in which they “choose a debatable question” and research it. “While they are independently researching and creating a presentation, I can call a weaker student to a private call and quietly work with them giving them the extra support they need,” she says. That would be harder in a noisy classroom.

And some students who shied away from participation are stepping up. “The quieter, more introverted students can participate more because they are not being seen by their peers,” says Peters.

Naima Charlier, director of teaching and learning at the Nord Anglia International School Hong Kong, says moving everyone online has had plenty of challenges but also has increased teacher confidence around technology and e-platforms. “There’s a massive energy about how to do this incredibly different and difficult thing as well as we possibly can,” she says. Teachers are trying and adjusting and sharing at warp speed what works and what doesn’t.

Sachdev agrees. “Teachers share far more than they normally world,” he said. “Every single teacher can see what others are doing, which isn’t how things typically work.”

No such silver linings exist for the millions of students who can’t get online, or whose schools and teachers do not have the resources to even experiment with e-learning. Depending on how long the pandemic lasts, governments may be forced to find creative ways to get more kids learning.

Technology

What happens to education technology after the coronavirus pandemic fades will rest in part on the quality of the tech itself. Not everyone is optimistic.

HolonIQ, a market intelligence firm for the education market, poses questions twice a year to a panel of more than 2,000 global education executives and investors across public and private institutions and firms, from pre-kindergarten to lifelong learning. In its most recent survey, half of ed tech firms said they were pessimistic about whether the coronavirus pandemic would make things better or worse in the short term.

“There’s a discussion now about how this is a golden era for ed tech, for digital transformation, but more than 50% of ed tech is saying that over the short term, it’s worse or substantially worse off as an organization,” said Patrick Brothers, co-CEO of HolonIQ.

Meanwhile, 91% of educational institutions say they will be worse, or substantially worse off in the short term.

Schleicher, from the OECD, said the pandemic will expose how ed tech has largely failed to do what would be most powerful: leverage the relationship between teacher and learner.

“The big question for me is will we develop an ed tech solution that capitalizes on the relationship between students and teachers, as opposed to just broadcasting stuff,” he says. “I think if we want to give this any chance of success for large numbers of students and learners, the teacher is going to be absolutely key,” especially in the younger years such as primary schools. Pair good teachers, who coach and facilitate, with good content and good tech, and the sky is the limit.

Adaptive, interactive, science-based learning platforms may start to take hold—especially for those using the opportunity of a crisis to help, rather than build market share. Starting in early February, Century Tech, an AI-driven learning platform for schools, made its platform free for all schools who need it. By March, it had expanded the offering to include all students who needed it, too.

Today, the British-based Century is giving training and access to its platform, which combines neuroscience and AI to individualize learning, to schools in 17 countries, including China, Vietnam, South Korea, Japan, the UK, Nigeria and Georgia. Founder Priya Lakhani says anyone who wants it can use it. “This is why we do what we do, and if we can help we should,” she says.

Innovations are abounding, but not in a coordinated manner. Saku Tuominen founded Finnish nonprofit HundrED five years ago, to research education innovations from over 150 countries. In those five years it has studied 5,000 such innovations and packaged 1,164 on its website, with ideas for everything from creativity, to the environment, to “forest schools.” Two weeks ago, HundrED pivoted to work full time on coronavirus. It is in the process of selecting from its library simple innovations that have the potential to work in many places in a home learning environment. One example: the Global Oneness Project, an interactive community series about storytelling in which filmmakers and photographers share their work and explain how stories can connect people.

HundrED is following up with those innovators to see how they are adapting them for the crisis. On April 3rd, a curated list of resources will be released; on the 7th, webinars will be available to train educators. “There is not a lack of tools,” Tuominen said. But he believes there is aren’t enough ways for the best ideas to be shared.

Beyond tech

So far, coronavirus has offered a stark reminder of the very human nature of schools. Peters, from the International School of Monza, has leapt into online learning, but cannot wait to get back into her building. “Being online, I don’t think you really get a true sense of whether a student is really engaged and properly understanding,” she said. Tech hasn’t solved that most basic of things. “I look forward to the social interaction with the students.”

Sachdev says it has been so hard for teachers to be removed from their students and from each other because teaching is such a human endeavor. “None of us are used to smart working,” he said.

His school’s own journey shows the power of community, along with agile learning. In the first week, he and his team focused on providing seven hours of online learning. By week three, they eased up, freeing up more time for one-on-one and small group support, as well as offline projects. They responded and adapted.

By weeks four and five, a small number of members of the school community were ill or had died. Students had lost loved ones. The school pivoted again. “It’s not about academics,” Sachdev said. “It’s all about wellbeing for students and parents, and managing that from afar.”