Read this ancient text to deal with coronavirus pandemic stress

In an action-oriented world, the guidance for dealing with the coronavirus crisis is particularly difficult. Much of what the general public must do to help medical professionals on the front lines of pandemic management involves not doing anything, at least not beyond the four walls of our homes.

In an action-oriented world, the guidance for dealing with the coronavirus crisis is particularly difficult. Much of what the general public must do to help medical professionals on the front lines of pandemic management involves not doing anything, at least not beyond the four walls of our homes.

Compounding the psychological strain of inaction is the difficulty of living in ignorance. We know little. No one can say when or if things will normalize—whatever that will mean in the post-Covid-19 world. So we can’t console ourselves with the notion that our isolation will be brief or that relief is on the way. There is no vaccine, meaning no guarantee that containment efforts won’t continue indefinitely or become periodically common should regular life resume.

It’s enough to drive a person mad, and some try to manage by reading the news. But the overwhelming message is that the story du jour is too big to truly comprehend. The mind can’t handle the scale and vastness, and if you’re not unraveling a bit, you must not be human. It’s natural to occasionally despair at the state of affairs.

But desperation is no way to deal, and certainly not with an emergency that has no visible end. As Cambridge University philosopher Anastasia Berg noted in the Chronicle of Higher Education this week, for most of us, these circumstances “call not for more epidemiological modeling…but for philosophy. The question—what should I do?— is, after all, a variant of the first philosophical question, namely, how should I live?”

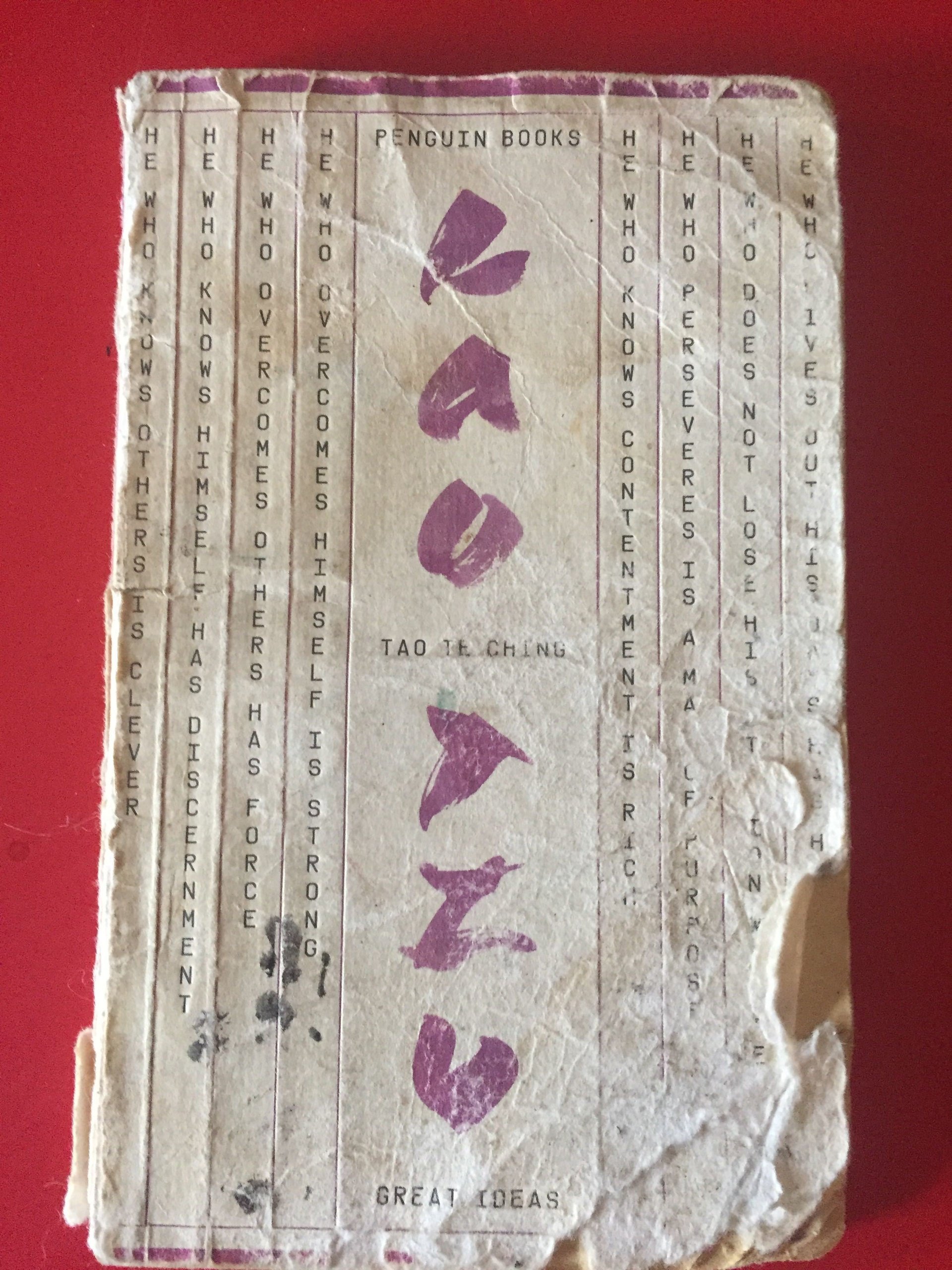

So if you need a break from this shared nightmare, the postmodern tsunami of information without answers, consider a different input. Flex your philosophical muscles and wrestle with paradoxical truths. Pick up the Tao Te Ching, or The Book of the Way, a text that has been guiding people for millennia and addresses the nature of the cosmos, being human, and the wisdom of not doing, all in a mere 81 single-page chapters containing just a few lines.

Your guide to the mystery of life

The Tao Te Ching is a terse and perplexing puzzle that illuminates everything. Mysterious, even after hundreds of readings, it helps make sense of the incomprehensible.

You can read it straight through or just open a random page—either way, you’ll surely find a confounding pearl to occupy your mind. Plus, its guidance is widely applicable, handy in good times and bad. It always helps to be familiar with the Tao. But never more so than now.

Appropriately for a book that takes on the great mysteries of life, the Tao’s origins are unknown. Some scholars believe the text is a compilation of wisdom first put together in the fourth century BC. However, that’s not proven and the much more fun version of the story—the lore repeated over centuries—is that it’s the product of one sixth-century BC Chinese philosopher named Lao Tzu who was pressured into sharing the fruits of his quest for truth before escaping civilization.

Lao Tzu was reluctant to discuss “the way”—the nature of creation and being—because he believed that “one who knows doesn’t speak” and “one who speaks doesn’t know.” Still, we’re lucky that he did because civilization has greatly benefited from the Tao. It is one of the world’s most influential historical texts–along with the Torah, Bible, Koran, and Vedas—a source of continual interest to scholars, mystics, and literati worldwide.

Translations and interpretations abound. Among them is novelist Ursula Le Guin’s 1997 rendition. Poet and Zen scholar Stephen Mitchell’s highly accessible version is available online in digestible bites at The Book of the Way, Day by Day.

This reporter’s favorite take is a brutally poetic lesson in tough love by sinologist and Chinese philosophy professor, the late Din Cheuk Lau of Hong Kong. Initially published in 1963 and still in print to this day, you can read it here for free. But this is a book to own and hold and carry with you everywhere you go (once you’re again free to regularly roam).

The text has withstood the test of time and transcended cultural boundaries because it explores challenges we all must face, most notably the yin-yang of fortune and misfortune. It offers hope in the worst moments and serves as a warning to remain humble when you’re courting lady luck. According to the Tao, “It is on disaster that good fortune perches; It is beneath good fortune that disaster crouches.”

Pick a passage

From the very first lines on the first page, you get a taste for the simultaneous simplicity and complexity of this ancient text that remains relevant to generation after generation. It begins, “The way that can be spoken of is not the constant way; The name that can be named is not the constant name.”

In other words, though the book holds truths, words are limited and the names we give things incompletely describe reality. We use the tools available to us—in this case language—but the text’s primary message is that the human tendency to make things easily comprehensible, our love of takeaways, is a weakness that prevents profound comprehension.

The Tao reveals that contrasts and seeming opposites are actually complements and complete concepts. Take for example, how it handles managing the pressing problems of this and all times—desire. Whether applied to wanting to know things when we cannot in the context of the pandemic, or wanting to shop, the text has an answer that’s deliciously simple yet difficult to swallow. It doesn’t advise giving up wanting or living in a state of constant longing. Instead, it says, try to do both. Simultaneously.

To understand the Tao, meaning the way of nature itself, you can’t be an either-or type. Lao Tzu advised that we always rid ourselves of desire to observe the universe’s secrets and at the same time continually allow desire in order to observe nature’s manifestations, its gifts and riches.

If this counsel is confusing, well, so is the world. In the current crisis, this advice makes a lot of sense. Be realistic about how little we know regarding the virus and when we’ll go back to some semblance of global health and normalcy. Wanting knowledge won’t change facts.

But also hope for the best. If people didn’t want better, we probably would not have evolved at all.

In Lao Tzu’s view, desire and lack thereof are not mutually exclusive or two different things. They are the same and only “diverge in name as they issue forth.” The sage admitted this was difficult to comprehend, explaining, “Being the same they are called mysteries. Mystery upon mystery—the gateway of the manifold secrets.”

Secret knowledge

The superficially contradictory positions that the Tao advocates stop seeming contrary when you sit with them. Your logical mind—desirous of easy answers—might have trouble taking this text seriously at first. How absurd, you may muse, this is for fools!

Lao Tzu anticipated as much. He tells us:

When the best student hears about the way, they practice it assiduously. When the average student hears about the way, it is here one moment and gone the next. When the worst student hears about the way, they laugh out loud. If they did not laugh, it would be unworthy of being the way.

If you think that’s silly, consider this morsel that will surely ring true. “It is easy to maintain a situation while it is still secure. It is easy to deal with a situation before symptoms develop.” That explains not only why we’re avoiding contact to prevent further spread of infection, but also why we should have been paying attention to the early warning signs that something dire was developing.

Now, so much of what we love about society has been abruptly halted because we refused to take the first signs of trouble seriously. But the unprecedented actions taken by governments belatedly, halting contact and with that entire economies, may well save us from disaster. As the Tao puts it, “The way that leads forward seems to lead backward.”

Managing paradoxes and contradictions and truths that seem mutually exclusive yet are simultaneously veritable is tough. It’s also how things go—and so it’s necessary. Life isn’t simple, and we don’t get better at it by acting like it is.