Shutting down the economy during a pandemic may be the best way to protect the economy

As the coronavirus pandemic intensifies, concerns are growing about the economic toll exacted by policies meant to contain it. Research published this week shows that aggressive social distancing measures, while extremely disruptive to commerce in the near term, can result in faster economic growth when the disease subsides.

As the coronavirus pandemic intensifies, concerns are growing about the economic toll exacted by policies meant to contain it. Research published this week shows that aggressive social distancing measures, while extremely disruptive to commerce in the near term, can result in faster economic growth when the disease subsides.

More than 670,000 people around the world have been infected with the novel coronavirus, and nearly 32,000 of them have died, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University. To save lives and slow the spread of Covid-19, a growing number of countries have resorted to lockdowns that are driving millions into unemployment and threatening a wave of bankruptcies. Wealthy countries have committed to spend and lend more than $4 trillion to try to protect their workers and industries from the fallout.

The economic price of widespread quarantines and business closures may be lower than the alternative, according to the research from economists at the US Federal Reserve and MIT, titled “Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu.”

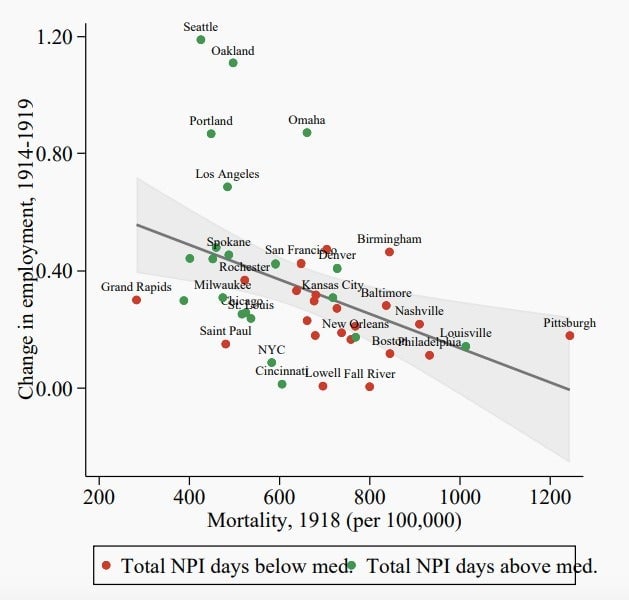

The researchers examined US cities during the 1918 flu pandemic. Places hit by the breakout suffered economically, but cities with “early and extensive” containment efforts saved lives, while their economies, measured in terms of manufacturing and bank lending, performed better when the disease abated.

During the 1918 pandemic, speed mattered. Cracking down on the virus’s spread 10 days earlier boosted manufacturing employment by about 5% afterwards, according to the researchers. Keeping in place containment measures—known as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs)—for an extra 50 days increased that sector’s employment some 6.5% in the period that followed.

“If anything, cities with longer NPIs grow faster in the medium term,” the economists wrote.

The research will add to the debate about how to limit the effects of the coronavirus. Donald Trump has argued that aggressive policies to slow the spread of the virus could be worse than the disease itself. The US president, who is running for re-election in November, has said he would love to have US enterprises open for business again by the middle of April. The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board argued that there’s a limit to the economic sacrifice society can make to safeguard public health.

The research from Fed and MIT economists suggests the tradeoff between public health and the economy may be neither as straightforward as it appears, nor as large as feared. “Cities that implemented more rapid and forceful non-pharmaceutical health interventions do not experience worse downturns,” economists Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner wrote. “Evidence on manufacturing activity and bank assets suggests that the economy performed better in areas with more aggressive NPIs after the pandemic.”