Public health officials have recommended a distance of six feet between people, or approximately two meters, to reduce people’s chances of spreading the novel coronavirus. The measurement has become a potent expression of social distancing. While it’s not a guaranteed way to avoid contagion, for many people, six feet has come to feel like the difference between safety and peril.

Around the world, people have devised various ways to denote the prescribed social distancing protocol using chalk marks, tape, floor stickers, signs, furniture and other crafty means.

Graphic cues are useful because people are generally terrible at approximating distances, explains Wayne Hunt, a celebrated “wayfinding” designer whose company, Hunt Design, has developed highway signage systems across the US. (Wayfinding specialists or environmental graphic designers work with architects, city planners, and businesses to create effective directional infrastructure.)

Hunt observes that people who live in packed urban areas tend to underestimate density. This might partially explain why New York City’s 311 public service phone number is receiving thousands of complaints about the lack of social distancing each week. The opposite is true for those who live in places with more expansive thoroughfares, like parts of California. “People here are overcompensating,” says Hunt, who lives in Los Angeles. “Someone walking their dog will give you a 20-foot berth.”

Hunt marvels at the ingenious ways people are communicating the social distancing measures in various places. “Everybody’s rising to the occasion with their own graphic language,” he observes “People solve problems intuitively. Professional designers give it a style and form, but it’s hard to beat what the store manager would do, for instance. I’m a big fan of the vernacular.”

But these graphic markers are only effective in certain environments like queues or waiting rooms, warns Hunt. “There is no diagrammatic or environmental signage solution for unstructured space where people move through in random ways,” such as in parks or playgrounds, he explains.

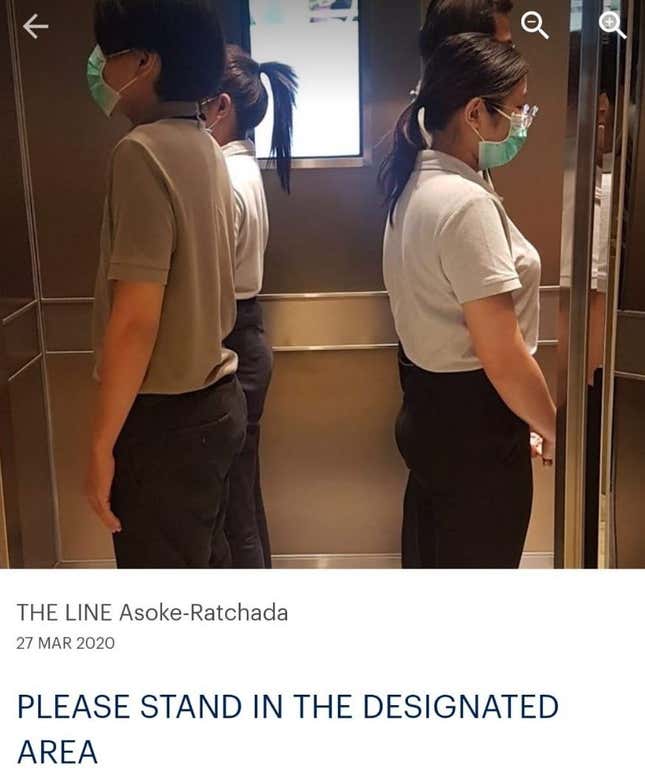

Elevators are particularly tricky. As one example from Thailand shows, it’s virtually impossible to observe social distancing in such tight spaces.

“My condo has signs inside the elevator suggesting that up to four people can ‘social distance’ as long as each person faces a corner,” Anna Marie Smith, an American expat based in Bangkok tells Quartz. “But the elevator is only big enough for four people to begin with. It’s not a very practical way to solve the problem of keeping people apart.”

“On the bright side, they have super-glued bottles of hand sanitizer inside each elevator. I guess that’s better than nothing.”

Some health agencies are offering familiar equivalents to help people comprehend the six-feet mandate. For example, a county in Florida with a healthy reptile population advises residents to keep “at least one large alligator between you and everyone.”

Our cultural background influences the way we perceive space too, as the anthropologist Edward T. Hall, discusses in the seminal 1966 book, The Hidden Dimension. Hall pioneered the field of proxemics, which studies how humans behave and feel in various spaces. He hypothesized that Germans generally require a bigger personal bubble than Americans and the Japanese embrace crowded spaces more than most Westerners, for instance.

Of course, these are sweeping stereotypes, which even Hall cautions against. His research, however, stresses the fact that collective traditions shape how populations compute their relationship with people and objects.

Six feet is a somewhat arbitrary distance, explains Dr. Kenneth Tyler, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “There’s no magic number. But the odds of breathing in infected, aerosolized particles drops as a function of distance from the person who is coughing or sneezing,” he explains in an interview with the hospital’s journal, UC Health.

Hunt says city planners and architects will have to rethink what public spaces will look like after the threat of Covid-19 dissipates. “Will people self-space in most public arenas? Will movie theaters need to isolate pairs of seats, losing revenue on the others?” he muses. “What about places where spacing is impossible like airplanes, trains, intersections and dozens of others?”

When that time comes, they will have a trove of homegrown designs to build on.