If you liked a piece of dangerous misinformation about the coronavirus on Facebook, then you’ll see a message urging you to read the facts.

It’s part of Facebook’s new strategy for walking a knife’s edge—quelling the spread of dangerous falsehoods, but without accidentally pushing users to spread them even more, out of shame or because the lies are seen as forbidden fruit.

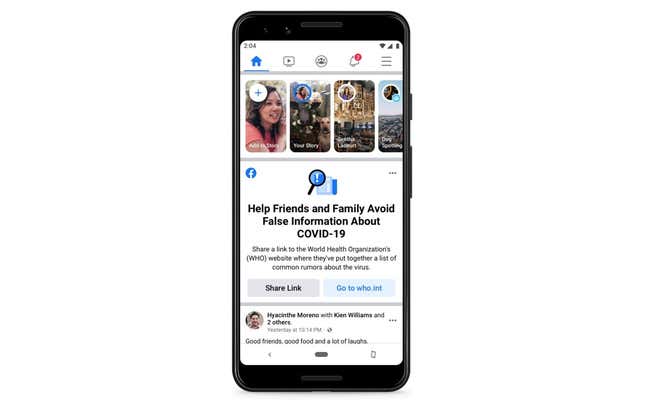

“Help Friends and Family Avoid False Information about COVID-19,” the alert will say then urging them to “Share a link to the World Health Organization (WHO) website where they’ve put together a list of common rumors about the virus.”

What’s important to notice is what the alert doesn’t say. It doesn’t tell the user they spread falsehoods, let alone shame them for it. If it works, that might be part of the reason why.

It’s a little bit like contact tracing: people who were “exposed” to potentially-dangerous falsehoods are alerted. They of course can’t be tested or quarantined, but they could be prodded to spread the correct info.

The misinformation on Facebook is rampant, from fake cures that are actually deadly to politically-tinged lies about the coronavirus being made in a lab.

In contrast with ads, sharing false stuff is generally allowed—it’d be impossible to sort true from false at a huge scale and, not to mention, a bit dystopian for a giant worldwide corporation to decide what’s true and what’s not.

Over past years, a greater focus on false information—ranging from things your former high school classmates mistakenly believe (“misinformation”) to lies spread on purpose (“disinformation”)—pushed Facebook to try to do something. Facebook’s favorite tool for solving problems is more algorithms. That’s been magnified by the crisis, which has sent its teams of contract moderators home. But computers are terrible at figuring out what’s true and what’s false. Instead, Facebook relies on a third-party fact-checking organizations—for misinformation about coronavirus or anything else.

It takes time for those organizations, staffed by human beings, find a post and, perhaps, choose to debunk it. In the meantime, Facebook’s complex, opaque algorithms keep chugging—often showing the false posts again and again and again, especially if they’re popular or prompt lots of reactions. Fact-checkers can’t keep up.

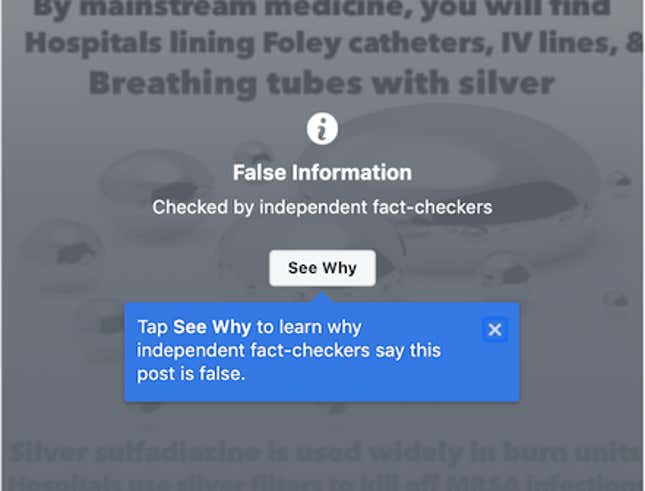

When a false post has been found and debunked by one of these organizations—which Facebook funds to a limited degree, having just announced $1M in grants—any instances of those posts on Facebook appears with a warning.

Facebook’s vice president of integrity Guy Rosen says it put up 40 million such warnings on 4,000 distinct posts in March. However, research from advocacy group Avaaz suggests it’s efforts aren’t enough, finding 26% of false content that had already been fact-checked still didn’t show up with a warning. Academic researchers have been trying to sort out when those messages are helpful. There’s no consensus, except that doing it wrong can backfire and reinforce the falsehoods.

Of course, we don’t know everything about the virus and how to treat it. Public health officials have changed their minds about whether masks are helpful for healthy people. And there’s no scientific answer yet, either, about whether hydroxychloroquine—a malaria drug heavily touted by President Trump—is actually helpful against coronavirus. With the jury still out, fact-checkers have a tough job.

That’s where Facebook is trying something new: urging users to post the WHO’s debunkings of popular rumors about garlic, 5G, and hand-dryers.