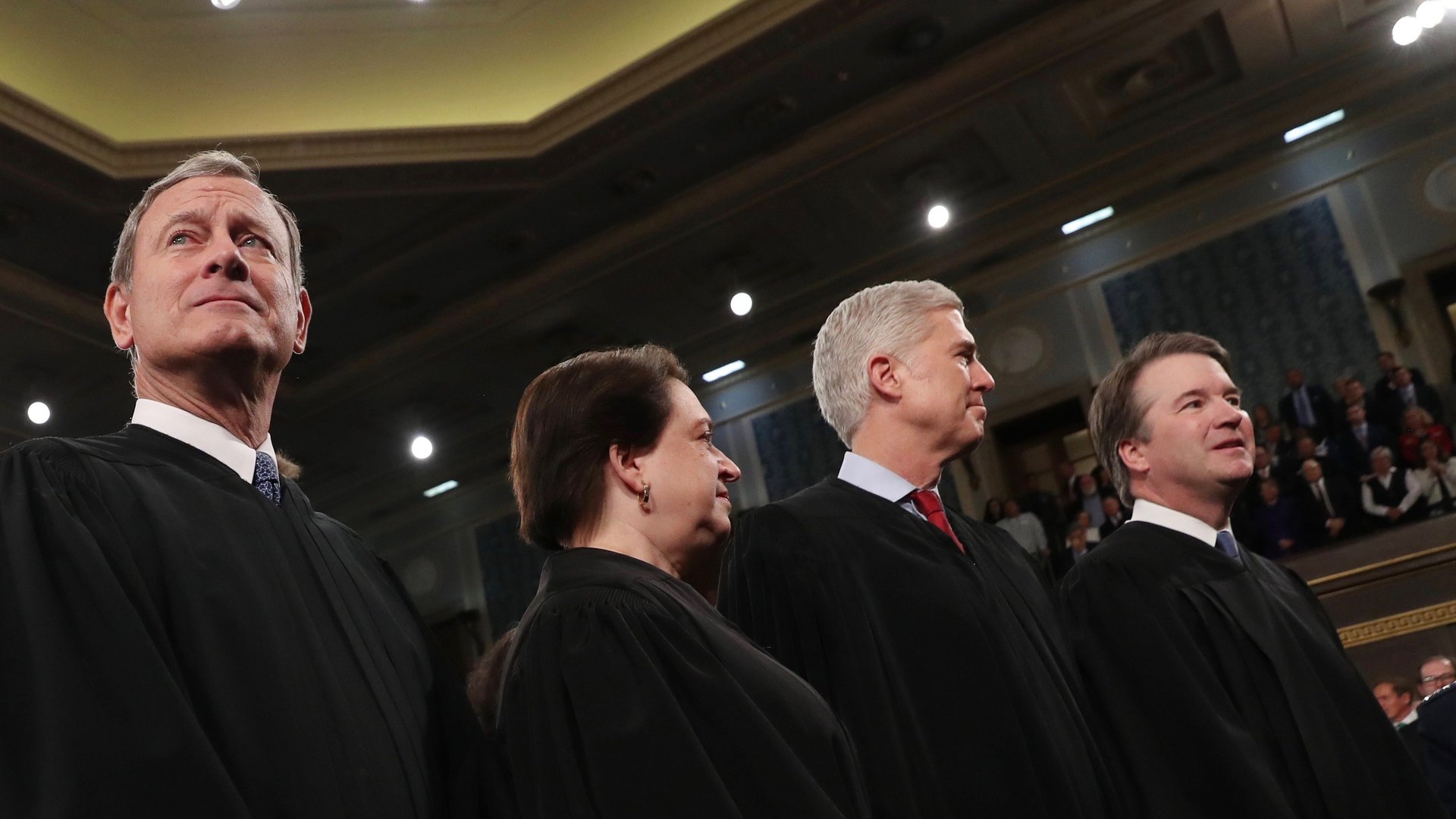

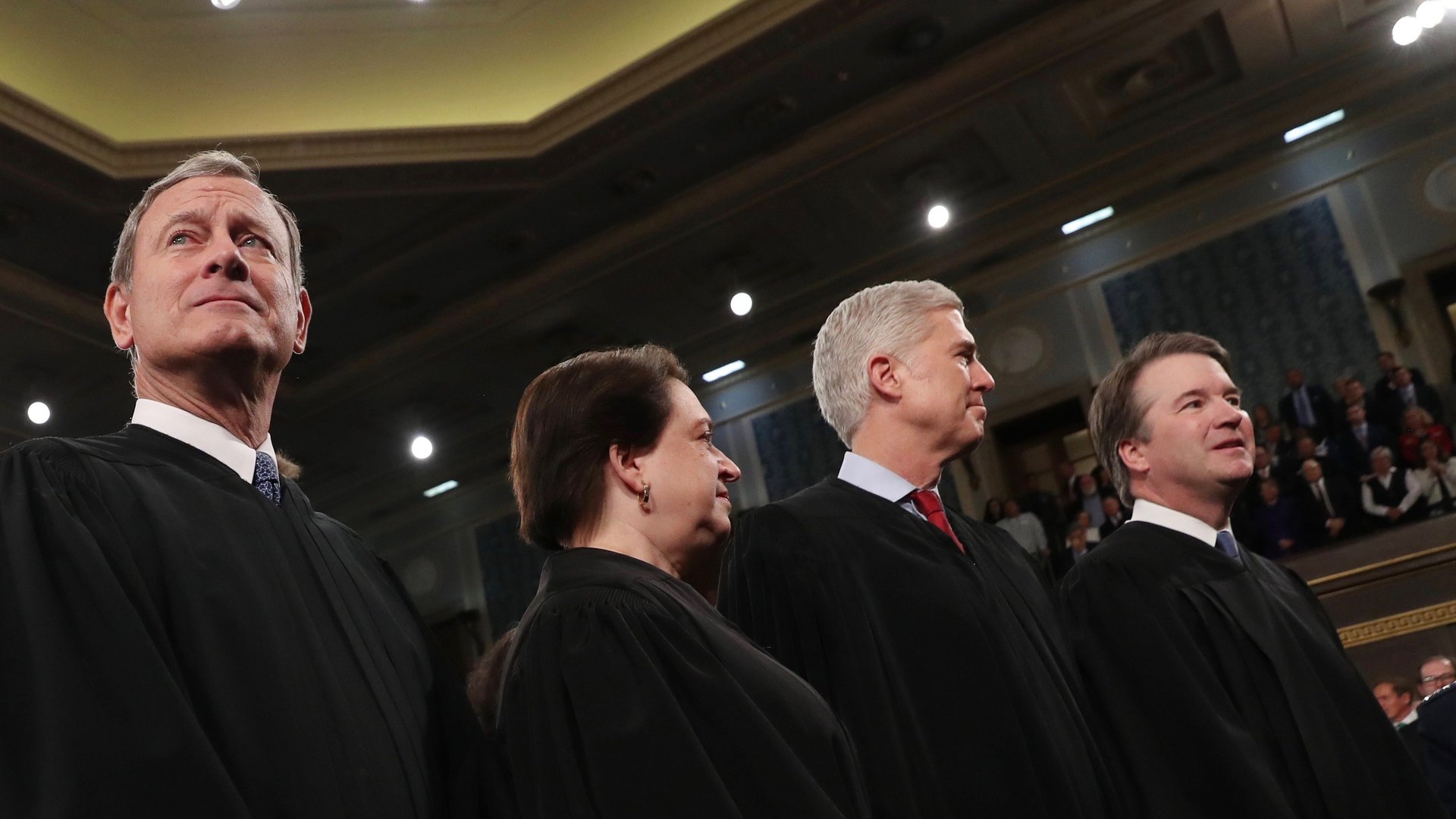

US Supreme Court chief John Roberts takes aim at Neil Gorsuch’s “evocative” claims in EPA case

The US Supreme Court today decided a case that pitted 98 property owners in the toxic towns of Opportunity and Crackerville, Montana against the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO). The matter apparently also put chief justice John Roberts at odds with his fellow conservative, Neil Gorsuch.

The US Supreme Court today decided a case that pitted 98 property owners in the toxic towns of Opportunity and Crackerville, Montana against the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO). The matter apparently also put chief justice John Roberts at odds with his fellow conservative, Neil Gorsuch.

The justices sparred in dueling opinions over the notion of “paternalistic central planning,” a formulation Gorsuch used in his dissent and one that suggested his colleagues in the majority were practically communists or—almost as loathsome—socialists. Roberts, for his part, defended a centralized approach to environmental cleanups under federal law and evidently resented his colleague’s claims.

The justices had to decide whether the property owners—with land on a federal Superfund site that ARCO’s Anaconda Smelter had poisoned—could sue the company in Montana state court for additional remediation of the site. Usually, the EPA negotiates, oversees, and manages Superfund cleanups. It had already settled with ARCO for $60 million. ARCO argued that the state suit is thus barred by the federal law that created the national cleanup scheme—the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). If every landowner in every state were able to also demand remediation of the land, it could lead to contradictory cleanup schemes that could be environmentally harmful, the company claimed, not to mention costly.

Ultimately, the court ruled that the property owners could sue ARCO in Montana court and, on this part, at least everyone agreed. Where the justices differed was on the extent to which the EPA had to be involved and call the shots if Montanans won their case locally. The majority ruled that the 98 individuals would have to run any plans for additional remediation of the toxic property by the federal agency, as the EPA must coordinate all environmental cleanup work there and ensure additional efforts don’t undermine or conflict with the agency’s plans.

Gorsuch, joined by Clarence Thomas, dissented. The justices would have allowed whatever remedy the property owners won in a local tribunal to proceed without EPA approval. Anything less was effectively holding the individuals hostage on toxic territory and amounts to an unconstitutional, uncompensated government “taking,” they claimed.

The company’s claims about the importance of coordinating with the EPA were essentially cover for its true position, which is that it doesn’t want to pay any more cleanup costs, Gorsuch hinted. As is his wont, he articulated his disagreement acerbically, arguing:

[L]et’s be honest, the implication here is that property owners cannot be trusted to clean up their lands without causing trouble (especially for Atlantic Richfield). Nor, we are told, should Montanans worry so much: The restrictions Atlantic Richfield proposes aren’t really that draconian because homeowners would still be free to do things like build sandboxes for their grandchildren (provided, of course, they don’t scoop out too much arsenic in the process).

Roberts seemed displeased with Gorsuch’s argument and the implication that his position was left of the ideological center, defending it as “federalist” instead. The chief specifically singled out Gorsuch’s dissent for a lashing. Roberts wrote:

We…resist justice Gorsuch’s evocative claim that our reading of the Act endorses ‘paternalistic central planning’ and turns a cold shoulder to ‘state law efforts to restore state lands.’ Such a charge fails to appreciate that cleanup plans generally must comply with ‘legally applicable or relevant and appropriate’ standards of state environmental law. Or that States must be afforded opportunities for ‘substantial and meaningful involvement’ in initiating, developing, and selecting cleanup plans. Or that EPA usually must defer initiating a cleanup at a contaminated site that a State is already remediating. It is not ‘paternalistic central planning’ but instead the spirit of cooperative federalism [that] run[s] throughout CERCLA and its regulations.

The ideological battle in today’s dueling opinions echoed sentiments expressed at oral arguments in December. Roberts last year had expressed concern that the property owners were being short-sighted and failing to see the bigger environmental picture. What if one of their remediation plans was already considered by the EPA and just hadn’t been implemented yet? Or, more dangerously, what if the property owners won in state court and instituted a plan that would somehow run afoul of the federal project because the 98 individuals weren’t aware of every governmental consideration?

Gorsuch, meanwhile, had advanced a claim that the property owners didn’t even make. He suggested that the federal government’s indefinite control over a Superfund site could be grounds for a constitutional claim that their land was being taken from them without just compensation. In his written dissent, he again presented that argument.

Practically speaking, however, the fight between ARCO and the property owners who want the company to pay for more cleanup isn’t over. The landowners won the right to keep fighting. The case has been remanded back to Montana state court. And if the citizens of Opportunity and Crackerville win locally, they will have the opportunity to make ARCO pay for more cleanup once the EPA has had a crack at their remediation plan.